Twenty years after the Stonewall Riots, I was graduating from Wesleyan University as a young activist. I had come out in college in 1985—first as bi, which was something of a first draft of the truth, and then as gay. Wesleyan held workshops then that every student had to attend in their first year, in which you role-played being gay and coming out for one hour, a practice that allowed those of us who were queer to experience telling the truth in a confidential setting, and allowed those who were not to understand something of the pressure of saying those words. By my senior year, I was leading these workshops. I knew enough of my history that when I organized the campus Pride celebration that year, and designed the T-shirt, it had an eye drawn with an upside-down pink triangle in it, hand-lettered by me and silk-screened in my basement—the triangle was the symbol the Nazis had placed on gay prisoners at concentration camps, re-appropriated by ACT UP.

I was, in other words, an activist like many of my generation of queer youth, educated at a liberal arts college, and terrified by both the AIDS crisis and the country’s reaction to it. I even had a gay mentor, an out gay professor who was working to create a queer studies program on campus. And yet I couldn’t tell you when I first heard the words “Stonewall Inn.” I just remember thinking it sounded like a place I could go to get chowder with my mom near my campus in Connecticut.

There is no license to be queer, as my friends and I used to say, no exam to pass. That is both a weakness and a strength of this identity, and it has always been this way. In 1989, I was someone who had come as close as you can to getting such a card, and if you had asked me then about the cause of the riots, much less why Pride was in June, I don’t think I could have told you, but I could have educated you on the current safe-sex protocols and infection rates for HIV, and, depending on when you knew me, I may even have done so. I thought the story of Stonewall did not have much to offer me, back then. The legend was that the riots of 1969 had inaugurated an era of gay liberation, of freedom to love, and yet as far as I could see, 20 years later, they had become the start of a global Pride industry apparently dominated by white gay men, selling an idea of desire—a young muscular white man, smiling and dancing without a care in the world. This seemed a contemptible goal then, and I didn’t understand it as a political aim.

I eventually corrected myself. After reading three books that mark the fiftieth anniversary of Stonewall, I have been corrected again, in some way I never anticipated. The militancy I felt as a young man grew from this tradition of remembering the riots without the real story of the riots, just as the distance I felt came from a political narrative whose imagery centered on whiteness and assimilation.

How do you honor a riot? The Stonewall Reader is one answer—an excellent companion to those famous bricks the patrons threw at police that night in June 1969, full of fury at the new intensity of police crackdowns. Divided into three sections—“Before Stonewall,” “During Stonewall,” and “After Stonewall”—this anthology, edited by the New York Public Library’s Jason Baumann, aims to correct a narrative that has so often excluded LGBTQ people of color.

Judy Garland’s death is often cited as a context for these riots, but in his foreword the novelist Edmund White adds the civil rights movement, the sexual revolution, and the antiwar movement. He acknowledges that a Mafia-owned bar with police protection is an unlikely staging ground for liberation, and he describes his own struggles—the fiancées he disappointed, the therapy that failed him—concluding, “I suppose the horror stories bore everyone.”

I just want to finish with one observation: Because of the Stonewall Uprising, people saw homosexuals no longer as criminals or sinners or mentally ill, but as something like members of a minority group. It was an oceanic change in thinking.

What’s interesting to me about this last line is that, as the anthology shows, the change White describes didn’t just happen in those people outside of the community, but inside the community—and inside him—as well.

By mixing familiar and unfamiliar texts, Baumann changes what you thought you knew about this moment and the people who made it. In the “Before Stonewall” section, excerpts from classic works—John Rechy’s City of Night, Samuel R. Delany’s The Motion of Light in Water, and Audre Lorde’s Zami—appear alongside letters that activist Franklin Kameny wrote to John F. Kennedy, urging him to support gay rights, and an interview with Ernestine Eckstein, an African American lesbian activist with the Daughters of Bilitis. Many describe their involvement in the other protest movements that White named; and writers and activists who might have seemed isolated are shown to have been in conversation with or a part of a larger movement. Sometimes the combination of texts is almost humorous: On one page, Eckstein says the “homophile movement” wasn’t ready for civil disobedience the way the civil rights movement was; then we go to the candid firsthand accounts of the riots—uncivil disobedience was what came next.

The brick is famous to us now, but less famous are the coins that protesters threw at the police, a way of saying they knew the Mafia had paid them off. The Reader doesn’t retcon the language of these forerunners—the word “faggot” was in common usage then, “scare drag” also (drag queens who scared the straights). The book de-gentrifies the narrative, returning the street-smart stories of the original protesters to history. The inclusion of Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson in the “During” and “After” sections also subtly underlines the role of transgender people, as they tell the story first of that night and then of how their abandonment by the movement began almost immediately. The book’s mix of familiar and unfamiliar didn’t just re-contextualize the riots for me. I came to understand myself and my life differently. I didn’t even know what I’d lost or gained from these stories and their contexts. The Stonewall Reader seems designed to be widely adopted in classrooms and should be, but, to be sure, it is for anyone, even those who think they know this history.

Much as the Reader recasts the riots, Indecent Advances, James Polchin’s fascinating new book on the treatment of gay men in true crime and crime fiction reexamines the violence that people at the Stonewall Inn had faced every day, and the rage crackling up underneath. True crime as a genre has often centered queer lives, but always, as Polchin observes, with queer characters as either the criminal or the victim of a terrible murder, involving either a secret and illicit love affair or an obsession, so that the moral of the story is that queerness and death are two faces of the same problem. Scandal as social control.

Polchin has read newspaper articles from the last century in order to look critically at the accounts of violence against gay men, alongside the development of true crime drama as a genre, and the way this tracked to the various LGBT political movements waning and waxing over the years. Stonewall then is rightly more of an anchor in his book than a subject. We move toward it in the timeline, chapter by chapter, as we might toward a city in the distance.

The similarities between the crimes here struck me again and again, often down to the methods the attackers used; I often thought I was losing track of myself each time I read that a victim’s skull had been crushed. A Navy scandal in Rhode Island in the 1920s—in which a young Franklin Delano Roosevelt recruited Navy men to have sex with the men who tried to pick them up in order to obtain evidence against them—reminded me of the “Stasi Romeos” of East Germany, state spies recruited to pose as gay men and have sex with them. Reading that the Navy investigation led to the possible expulsion of the recruits for having violated the Navy’s prohibition against sodomy even while on an official mission for the Navy to commit sodomy felt like a premonition of the ruthless, win-at-all-costs political moment we’re living in now.

What makes Polchin’s readings stand out is the way he pursues an underlying story across several seemingly separate crimes. He is interested in the way the stories of these crimes, their prosecution in court and in the press, are shaped by socioeconomic class and race. Time and again, a white man who murdered a gay man of any race was let off if he employed the “gay panic defense.” But that familiar term obscures how, say, a Jewish rabbi murdered for “attacking” a young white man played into anti-immigrant and anti-Semitic hatred. If the killer was nonwhite, however, he was recognized as the aggressor, and the victim was then described as having been lured to his death. Homophobia, posing as a defense of heterosexual men, gave generations of white men tacit permission to kill any “sexual deviant” if they felt threatened.

Polchin also takes on readings of some famous gay novels, like Gore Vidal’s groundbreaking best-seller, The City and the Pillar. The novel’s original ending centers on a brutal murder straight from the headlines—a gay man enraged by a rejection kills the man who had helped him first experience his desires, but who was less certain of his queer identity. Polchin includes a note that Christopher Isherwood wrote to Vidal, concerned that such an ending would make people see gay men as violent. That concern seems almost ironic when you consider that in fact critics at the time almost uniformly decried the novel’s attempt to normalize homosexuality. Many years later, Vidal would change the ending to a rape—hardly an improvement—but Polchin underlines how many of the classics of gay fiction utilized the same tropes as the homophobic media, effectively participating in this project of criminalizing or pathologizing homosexuality.

It is interesting to note James Baldwin took this form of story to task in a 1949 essay that Polchin quotes. Yet Polchin doesn’t acknowledge that Baldwin himself would write Giovanni’s Room seven years later, a year after Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mr. Ripley, each effectively another volume in a literature in which, as Baldwin put it, “the avowed homosexual ... murders his first and perfect love.”

The book asks or leaves open some questions like these, alternately provocative and provisional. It also focuses largely on gay men, with fewer details on trans identities, bisexuality, and lesbianism, which all figured in these stories. Perhaps this book is best thought of as an opportunity for other scholars to take the project forward, in an act of intellectual ice climbing on the sheer face of a culture animated by the sexual control of men, that criminalized queer desire at every level in the service of the protection of white innocence.

It is something of a relief to turn to Perry N. Halkitis’s Out in Time: The Public Lives of Gay Men From Stonewall to the Queer Generation. Halkitis is a professor and the dean of the School of Public Health at Rutgers University and has written extensively on the lives of gay men affected by AIDS, as in his previous book, The AIDS Generation. While violence is not absent from this survey of the coming-out stories of men, it is not at the book’s center either. Here Halkitis sees as his real topic the role that each generation since the 1950s has taken on in the struggle for equality.

Halkitis writes about coming out as a public health imperative, pointing out the reduced health outcomes for gay men in the closet. He defines the Stonewall Generation as men who came out from the 1950s to the ’70s, taking up the struggle to love openly; the AIDS Generation as men who came out in the 1980s and ’90s and fought to protect that open love and defeat the worst ravages of the AIDS epidemic; the Queer Generation as men who came out from 2000 to 2010 and engage with the complexity of the full spectrum of genders, sexuality, ethnicities, and classes now encompassed by the struggle for liberty. Despite these definitions, he weirdly excludes what I might call the PrEP Generation, the men aged 31 to 41 who began a new era of sexual experimentation, previously unimaginable in the AIDS Generation, created by the advent of the HIV prophylaxis.

He interviews five members of each of these generations, across a mix of social classes, HIV statuses, and ethnicities. There’s the older black man who remembers seeing James Baldwin on television saying, “I thought I’d hit the jackpot,” when asked how he felt about being gay, black, and poor. The white, gay, working-class man who followed his parents’ instructions on how to buy half-price theater tickets and accidentally saw The Boys in the Band when he was 15. And the 19-year-old Chinese-Mexican-American young man who came out on Facebook to his family and friends. To go in 50 years from fearing murder and social death if your sexuality was revealed to simply posting on Facebook—that is what all of this has come to, even if it wasn’t always what it was for. Halkitis’s book is another crack in the darkness around queer lives, embracing the intergenerational conversations now possible and the unprecedented sharing of knowledge and stories that has really only just begun after these long decades of violence.

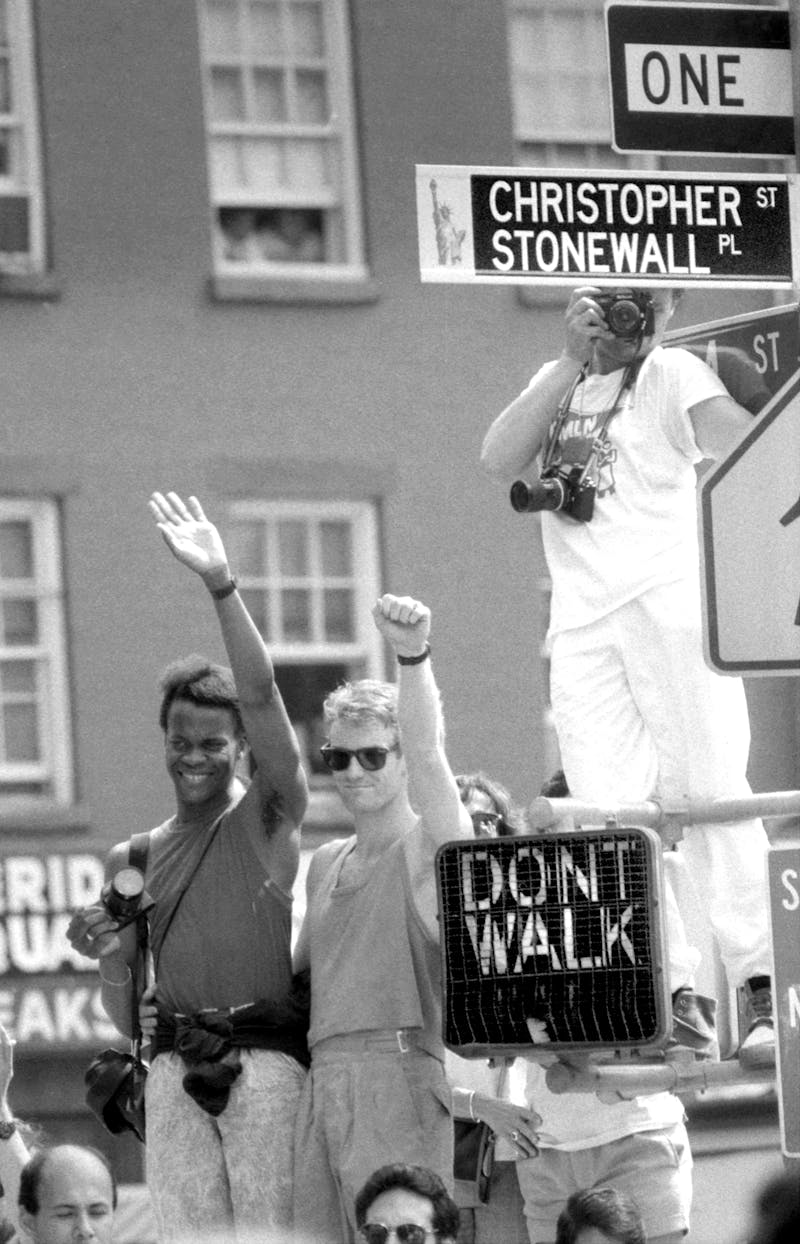

When New York City hosts this year’s WorldPride on the fiftieth anniversary of Stonewall, many people will observe it without truly ever knowing, much less understanding, why it is being observed and what exactly happened. This has been true for decades. Remember if you can, then, that the now-annual critiques of Pride™, the rainbow flags and slogans, and the performances honoring the trans activists central to the events of that week in 1969, are all, in their way, respectful traditions. And that few things could honor the spirit of those who fought that day like questioning the presence of the police in the parade, or dancing on the closed street in front of the famous bar that was once among the only bars in New York where we could dance. See if you can feel the joy so many have fought and died for, even if just for a moment, before you go back to fight again. And read your history, as much as you can.