“In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God.” So reads the opening verse in the Gospel of John—the fourth, deviant gospel—which was probably composed 70 years after the crucifixion of Jesus. According to Giacomo Sartori, John the Apostle got it way wrong. The Word comes toward the end of days, these days, our days, when the earth is already melting, when exodus or exile marks most of the world’s population, when God finally sits down (does a god sit?) and starts a “diary,” where he records his fumbling attempts to think, to write, to fall in and out of love. To become more human, if you will, to know what a mistake feels like, and to try to make it right.

It’s a kind of memoir, this novel, in which God recounts his obsession with a tall, lanky, promiscuous lab rat, a young woman who’s smart enough to enlist bacteria in the production of clean energy, but who just can’t find the right man. “Could it be me?” That’s God asking, knowing, like any other man, that even if He became a human being and sought her out, he might fail to charm her, or even to speak a complete sentence in her presence.

The line the author, God or Man, crosses in criticizing the human species is this: We humans are the only creatures who know that death waits for us. We acquire that knowledge around the same time we’re born into language. Knowing that we’ll die makes us neurotic—fearful, fretful, self-conscious—and this is also what makes us human, this is what makes us tell stories, about ourselves among others. And so Sartori’s God becomes human, and knows it, insofar as He writes. It’s terrifying.

Is Giacomo Sartori, a soil scientist (for real) and the author of seven novels, just another “new atheist,” making fun of religion because it’s irrational? God, no. This novel is an utterly serious and wildly comic test of the strange idea we take for granted in reading prose fiction—the pretense of the omniscient narrator. Here he is, God-like in his knowledge of past, present, and future, and yet he’s also explaining his very particular needs, desires, urges, trying on an imagined embodiment, what would come of being a man rather than a god. All good writing, fiction or non-fiction, makes this move by placing us in a world elsewhere, taking us out of ourselves, letting us live another’s life. By speaking in the voice of God, Sartori has simplified the premise and complicated the result of writing as such. This “diary” teaches its author that perfection of any kind is inconceivable. And so he finds he’s condemned to keep revising his own creation.

Sartori’s God has good reason to doubt himself. The woman he has fallen for is a serious scientist as well as an atheist and an anti-Catholic activist (she steals crucifixes and burns them for fun). Her day jobs include the artificial insemination of cows, which requires anal penetration up to her shoulders and gentle manipulation of bovine cervixes. We know this because God keeps a close eye on her day and night—no, of course, He doesn’t sleep, He has better things to do.

Like what? Like, coast carefree between galaxies, watching them mate, or be swallowed, individually, by black holes. (He loves every one of his creations except snakes and languages, both of which, the reptiles and the metaphors, make Him deeply anxious.) Or, cause Giovanni the seducer to shatter his elbow on his way to a tryst with the tall one, Ms. Einstein as He calls her. He’s a jealous God. Or, find ways to mend the broken life of the beanpole, as He also calls her, a victim of both sexual harassment and discrimination in her workplaces. He believes, as do most of us human beings, that everybody is equal in the eyes of God, and that sometimes we can bend that fabled arc of history toward justice.

This God, the brilliant, hilarious, and utterly believable creation of Sartori, has some trouble with Jesus. He was probably a bastard son, and God knows he said some crazy shit in his short span on earth. The formal complaint is clear. If God is a man—he called himself the “Son of Man,” for God’s sake!—what’s the point of having a monotheistic deity hovering over the earth, giving providence a good name? Church or no church, Holy Roman Catholic or otherwise, Jesus is at best a nuisance, at worst an atheist, either way a heretic. He shows up mainly in exasperated footnotes. “If I were ever to try incarnation, I certainly wouldn’t imitate my self-proclaimed offspring. I wouldn’t go around proselytizing barefoot, or pronouncing shamanistic phrases, as often as not false, or perform miracles.”

Sartori is, I believe, retracing the two itineraries that still claim our literary imaginations whether we know it or not, those biblical epics we call the Old Testament and the New. The God of the Old Testament was as obsessed with Job as Sartori’s God is with Ms. Einstein. As Jack Miles demonstrated in his wondrous biography of God, the chastened deity retreated from His providential role on earth when He understood the huge mistake He made in torturing his faithful servant, the observant and obsequious Job. God eventually delivered His own son as compensation, as substitution, as a sacrificial offering to His own creation, for having failed it once again. (Remember Noah.)

And then the Son of Man, sent on an impossible errand into this earthly wilderness, learned what it’s like to be a human being—nervous, fragile, unhappy, always looking for a way out, charged as a criminal, tortured, and executed in disgrace. Sartori combines Father and Son in the comical reach and tone of His voice. His? The Father, the Son, and the Holy What? They’re all gathered here in the sight of God.

Sartori’s God knows that our neurotic condition delivers us unto narrative, religion, art, and every activity that involves symbols and metaphors, which are just fancy words for big mistakes—a sail for a ship, a skirt for a woman, a man for a god, some paint for a person, a word for a thing. This writer, a garrulous god, worries over every word, footnotes included. “You write,” He says, “and the more you write the dizzier you become, and you end up with a headful of foolishness.”

We, the animals who claim to be human, name things—children, pets, places, times—because we know they’ll pass, just as we will. There’s no point in naming anything that won’t die. The name itself is already a commemoration: the desolation of time is built into the designation. That’s why it takes God so long to name the object of His desire, Daphne. He doesn’t get around to it until He’s exactly halfway through His “diary” (p. 99 of 206), when her life falls apart and He must repair it. For His desire has changed her world.

If you’re immortal, you can’t care much about what should endure because you know that none of it will, except you. If you’re not immortal, you can, and you do, and you try to find the words to make it significant. You want the words, the names, the memories, to last. So the fear of death and the urge to write are pretty much the same thing. But here, in this antic novel, God Himself fears death, or, what is the same thing, the extinction of His desire for Daphne. He wants to be embodied, but He knows that if He tries, he’s sooner or later a dead man. He hedges that bet.

We don’t have that choice. We have perfected the correlation between dying and writing by making big mistakes, and calling them myths, or novels, or poems. The memoir now competes with these genres because the real world has become unbelievable—the news reads like science fiction. Also, because we know that everyone has a story worth telling, and that he or she can tell it.

Still, the urge to write about this world, whatever the genre, remains a fundamental error—it mistakes the words for the things (or the events) and is, therefore, a fiction. When it works, the error itself is incorporated in the real world, and lets us behave accordingly, as if mere ideas might organize the future, as if the writer’s mistakes could become truths, or already are. Suddenly we believe in the world the writer has created, and we go from there. We’re transported, but not literally. Sartori’s God knows this in His bones (if gods have bones).

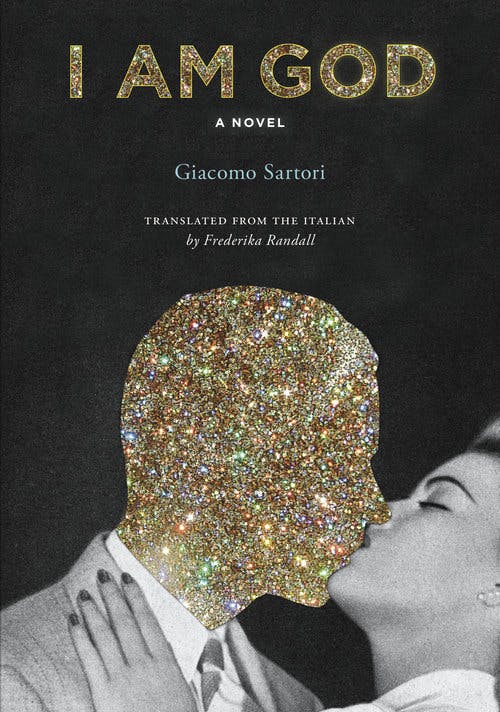

This urge to err and therefore to create is the human condition. The writer succeeds and the reader believes, no matter the genre, insofar as both know that they’re collaborating in making something that exceeds the present—it isn’t yet true—and thus permits a future that didn’t exist before the writing and the reading. Under Sartori’s verbal spell, made new by Frederika Randall’s translation, God now joins us in wondering where his big words, his big mistakes, will take him.

Other species know the fear of death, of course, but only at the hour, when they’ve made their only mistake and have been hunted down—they don’t anticipate it, they experience it. We instead remember death before it happens by building cemeteries, celebrating the dead, enclosing huge spaces that have no function except to console us, and to remind us that we’re headed for the same place. We remember what hasn’t yet happened by writing about it, by conjuring what we have lost before we even know what that is, or will be. What better definition of omniscience could there be? No wonder Sartori’s God is a writer.

He has seen what he loves disappear, and, like any other writer, equipped with mere words, he tries to make it reappear. As the world he made melts down, he creates another atmosphere, this one made of remembrance, but it’s the present, only now, only here.