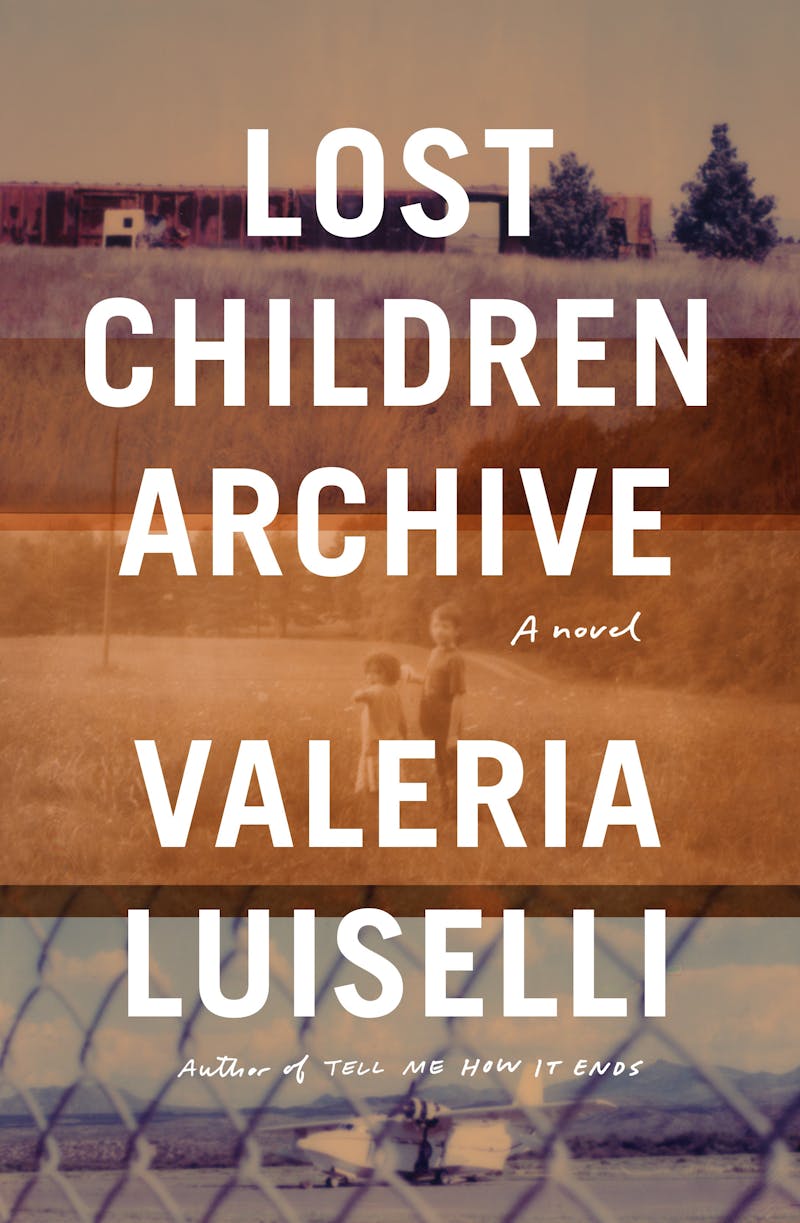

“Perhaps the only way to grant any justice” to the refugees who have died in the Sonoran and Chihuahuan Deserts, or anywhere on their journey toward a dignified life, Valeria Luiselli wrote in her 2017 essay Tell Me How it Ends is by “hearing and recording [their] stories over and over again so that they come back, always, to haunt us and shame us.” This story, she writes, must be “narrated many times, in many different words, and from many different angles, by many different minds.” Her essay chronicled Luiselli’s time as a court interpreter for undocumented children facing deportation in New York City; with her new novel, Lost Children Archive, she turns to the stories of the children who never arrived.

The plot reads as if ripped from 2018’s headlines, even if it is ostensibly set sometime in 2014, when over the course of nine months the number of child refugees from Mexico and Central America detained at the southern border of the Unites States surged to over 80,000. The authorities saw the “crisis” as a problem to be managed—what do we do with all these children?—rather than reckoning with the conditions that prompted their flight. “No one thinks of the children arriving here now as refugees of a hemispheric war,” Luiselli writes. “No one is asking: Why did they flee their homes?”

The surge of young refugees prompted the Obama administration to create a priority juvenile docket, so that the immigration cases of unaccompanied minors from Central America would go to the top of the court’s list. The effect was as intended: A greater number of children were deported back to the intolerable conditions they risked their lives to flee. “In legal terms,” Luiselli wrote in Tell Me How it Ends, the priority juvenile docket was a way “to avoid dealing with an impending reality suddenly knocking at the country’s front doors.” That reality is still knocking. During the month I read Lost Children Archive, tear gas was being launched from the U.S. side of the Tijuana border at members of the migrant caravans that walked from Honduras to Baja, California and two Guatemalan children, Jakelin Caal Maquin, 7, and Felipe Alonzo-Gómez, 8, died within weeks of each other under the custody of Customs and Border Protection.

How can one make art that takes such an issue as its theme, or that, more importantly, honors the lives of its most vulnerable victims? How can one not?

Lost Children Archive begins with a family packing for a road trip across America’s Southwest. Their trunk contains seven bankers boxes of their “collected mess.” Boxes I-IV belong to the husband, a sound documentarian who has recorded “echoes” of Apache history throughout the Southwestern landscape. He packs notebooks with titles like “On Documenting,” “On Listening,” “On Reenactment,” and a treatise on Native American history. The mother, a radio journalist reporting on the growing “immigration crisis” at the border, fills a box with reports and maps of migrant deaths in the desert. The final two boxes belong to the older son, 10, and the younger daughter, 5, who gradually accumulate notes and Polaroids from their trip.

This collected archive gathers and presents the sets of concerns of the story: questions of family-making, historical awareness, and political responsibility. It also points to what can never be recorded—the stories of the refugee children lost to the desert through which the family travels, children who have “lost the right to childhood.”

“The story I need to tell,” the mother narrates, “is the one of the children who are missing, those whose voices can no longer be heard because they are, possibly forever, lost.” Yet, that’s not quite what Luiselli does: Rather than write a novel in which she fictionalizes the lives of migrant children, she has written a novel all about the impossibilities and difficulties of creating such a novel. The mother, too, spirals into doubts as she considers her own audio piece on the plight of migrant children facing deportation: “Political concern”: “How can a radio documentary be useful in helping more undocumented children find asylum?” And even if it could, is she the right person to make it?

Constant concerns: Cultural appropriation, pissing all over someone else’s toilet seat, who am I to tell this story, micromanaging identity politics, heavy-handedness, am I too angry, am I mentally colonized by Western-Saxon-white categories, what’s the correct use of personal pronouns, go light on the adjectives, and oh, who gives a fuck how very whimsical phrasal verbs are?

These concerns could be read as Luiselli’s thinly-veiled anxieties about her own books. One of the novel’s most insistent themes is the tension between preservation and exploitation. When looking through her soon-to-be ex-husband’s boxed archive, the narrator finds Sally Mann’s Immediate Family and senses Mann’s portraits confessing that each “moment captured is not a moment stumbled upon and preserved but a moment stolen, plucked from the continuum of experience in order to be preserved.” She plucks from the lives of her own children—in one of the novel’s first scenes, she and her then-new husband record her daughter farting while she sleeps. But later she hesitates: “I don’t want to turn this particular moment of our lives together into a document for a future archive.”

The mother is not the only character in Lost Children Archive who borrows from others. The husband is intent on recording “an inventory of echoes” of the Apaches (if you are confused by what this actually means, you are not alone; at one point, he records the ambient sounds of Geronimo’s grave.) These echoes are meant to represent an “absence turned into presence, and at the same time, a presence that makes an absence audible.” The metaphor gets a bit overcooked throughout the novel—at times it feels like echoes echo the echo of other echoes echoing. Characters in a book the mother reads to her stepson echo the “real lost children” migrating across the desert, who echo the mother’s own two children who, in their own games, echo “bands of Apache children,” and who, later in the novel, like “the real lost children” end up lost themselves. While an echo can be revealing, it can also just be repetitive.

Amid these reverberations, Luiselli’s narrator voices her suspicion that the methods of storytelling cannot sufficiently represent contemporary experience. “Something has changed in the world,” she writes. “We don’t know how to explain it yet, but I think we all can feel it.” While driving through North Carolina, the family walks into a bookstore and the mother overhears a book club in the middle of a discussion. What follows is a comically rendered consideration of the purpose and efficacy of autofiction. The members say things like, “Despite the quotidian repetition … the author is able to hinge on the value of the real.” The consensus of the group “seems to be that the value of the novel they are discussing is that it is not a novel. That it is fiction but also it is not.”

The comment is very pointed, since Lost Children Archive, while not necessarily a work of autofiction certainly has its own heavy-handed dose of truthiness. If the novel is and is not fiction, and the mother narrating is and is not Luiselli, Luiselli can evade the potentially uncomfortable questions raised in her nonfiction. “Why did you come to the United States?” Luiselli asks the children in Tell Me How it Ends, and she also has to ask that of herself. While she doesn’t offer an answer, her own story of immigration—the right kind of immigrant with the right documentation for the right process—serves as a foil to the stories she translates. We don’t know what the mother’s story is in Lost Children Archive, or how her experiences relate to or contrast with those of the refugees. Her family, we are led to believe, is ambiguously brown. The mother was not born in United States; the husband “was also born in the south,” but their own story of migration is curiously absent.

Things get murkier when it comes to the husband’s fascination with Native American history. To be sure, the novel’s insistence on connecting colonial genocide and the current immigration “crisis” is incisive. But what is the husband’s own relationship to settler colonialism? When pressed on why he had become suddenly fascinated with the Apache, and with Geronimo specifically, the husband’s mumble of an answer—“because they were the last of something”—leaves too many questions unanswered in the text.

The most telling gap in the story comes when the two children decide to get lost in the desert. Midway through the book, the point of view shifts from the mother to the son, and we follow him and his sister as they walk from western New Mexico into the Chiricahua Mountains, and, over a 20-page-long sentence, the son’s narration is transposed with the stories of refugees crossing the border. This turn is at once mesmerizing and baffling—the many children’s voices become merged and disembodied, their experiences crescendo into a somewhat mythical unreality.

More than once, the mother has wondered aloud how her own children would fare under the circumstances faced by child refugees. When the children play a game of reenactment, imagining themselves thirsty and lost in the desert, the mother first finds the game “irresponsible and even dangerous” but then wonders if “any understanding, especially historical understanding, requires some kind of reenactment of the past.” She asks, “I wonder if they would survive in the hands of coyotes, and what would happen to them if they had to cross the desert on their own. Were they to find themselves alone, would our own children survive?” The same question appears in Tell Me How it Ends: “Were they to find themselves alone, crossing the desert, would my own children survive?”

These questions are meant to elicit empathy—if one can imagine one’s own children facing such horrors, one might care more about the horrors that other children face. But to ask, what if it were me? elides a more uncomfortable question: why is it not? The first question does little more than allow the mother to believe that she has carried out some form of moral reckoning, albeit from her own position of relative safety as, presumably, a documented immigrant or a citizen (the book surprisingly never clarifies this). The second question might reveal how her family’s position of safety benefits from the same state apparatuses that allow such horrors to even exist. That question implicates them; it suggests that understanding might require, more than empathy, a sense of political responsibility.