Anthony Bouchard, who often sports a waxed handlebar mustache that recalls the outlaws of the Wild West, has a habit of showing up at public events where everyone is unarmed and explaining that they’re in danger. In 2011, as the executive director of the hardline Wyoming Gun Owners, he attended a Casper City Council meeting with a handgun holstered at his hip. “Law-abiding citizens aren’t the ones you have to worry about,” he said. The council subsequently banned guns in city meetings.

In 2017, as a freshman state senator, Bouchard confronted three African American students about their presentation on gun violence and race at a University of Wyoming symposium. “He was quite menacing and threatening,” Allison Gernant, the students’ instructor, told me. “There were scare tactics. Like, he said, ‘I’d like to bring a bomb onto campus and set it off and see how long it would take for the UW police to get there.’” (Bouchard accused Gernant of “political race baiting to promote gun control” and described her account as “FAKE NEWS.”)

Bouchard is on a mission to eliminate “gun free zones” in his state, and the University of Wyoming is a top target. In 2017, he introduced a bill that would allow students to carry concealed weapons on campus. It failed, and this year he reintroduced it as part of a broader bill expanding liberties for gun owners. This time, rather than emphasizing the hypothetical dangers of an unarmed campus, he pointed to the precedent of other campus-carry states, such as Utah. “They’ve been doing it for 20 years, and it works,” Bouchard told local journalists. The bill lost a Senate committee vote in January, but gun rights activists in Wyoming aren’t giving up on the issue.

“It’s all the same arguments every time we have any kind of gun bill,” Bouchard lamented after the bill failed in the Senate. “The sky was going to fall, danger’s happening. It’s all the same argument, and it’s emotional. They’re not looking at the reality.”

This is a common refrain among campus-carry advocates. In the six states where such laws have been proposed this year, supporters have argued not so much that it’s necessary to protect students, which is a hard sell, but that it has proven harmless in the states where it’s allowed in some form. In West Virginia, the state director of the NRA said that in states with campus carry laws, “once the hypersensitivity of the issue subsided, there’s been absolutely no problems.” In Florida, a state representative told the Orlando Sentinel that “none of the things university presidents said would happen [actually] happened.”

I teach at the University of Texas at Austin, where campus carry was implemented two and a half years ago. At the time, newspaper reporters and TV crews from as far away as Tokyo covered the massive protests on our campus, which featured the spectacle of thousands of students waving dildos (because Texas regulates sex toys more rigorously than firearms). Since then, many have claimed that campus carry has worked out just fine. “Concealed carry poses no danger on Texas college campuses,” Governor Greg Abbott tweeted. “The dire consequences never happened.”

Could it be that, despite all the agita in academia, campus carry has turned out to be no big deal? That depends on how you measure its impact. There has not been an outbreak of gun-related violence at schools in campus-carry states, but that was never opponents’ main worry. Rather, they’ve argued that the presence of guns on campus would end up costing millions of dollars and would negatively affect schools in less quantifiable ways—impacting pedagogy, institutional reputation, campus atmosphere, and the recruitment and retention of faculty and students.

The evidence to support those warnings is growing, and there may well be fatal consequences that few foresaw.

Three decades after he penned the Second Amendment, James Madison served on the six-member board that banned students from carrying guns and ammunition on the University of Virginia campus. Thereafter, guns were prohibited at American institutions of higher education as a matter of course. That all changed in 2004, when the state legislature in Utah passed a law that stripped public colleges of the authority to establish their own policies about firearms. The new law wasn’t precipitated by any particular event; there hadn’t been any mass campus shootings in the state, nor any recent high-profile college shootings anywhere else in the country. (The 1966 sniper attack at UT Austin was by then a distant memory.) The University of Utah fought in court for the right to set its own firearms policies, but lost.

Other states did not immediately follow suit. But in 2007, the Virginia Tech massacre led to the formation of the group now called Students for Campus Carry, which quickly gained membership and attention nationwide. With support from SCC—and, to a lesser extent, the NRA—dozens of campus-carry bills were introduced in statehouses over the proceeding decade, many only passing after a second or third legislative session. Other states, such as Colorado and Oregon, adopted campus carry when universities lost court battles with gun rights advocates. Today, a complex patchwork of state laws makes it difficult even to say with clarity how many “campus carry” states there are. (Eleven have permissive laws similar to Utah’s; 16 ban guns completely; and 23 at least nominally allow guns on campus, but with more stringent restrictions and various caveats.)

The ostensible goal of campus carry was to empower armed civilians on college campuses to defend themselves and others from mortal danger. That has not yet happened. “Campus carriers have not intervened in any incident anywhere in the country on a campus,” said Stephen Boss, a professor of environmental dynamics and sustainability at the University of Arkansas.

For his new book, College Homicide: The Case Against Guns on Campus, Boss examined every campus homicide in the United States between 2001 and 2016. He found no direct interventions by campus carriers, and no deterrent effect. Murders are rare on campuses that allow concealed carry, but no rarer than on college campuses where guns are banned. “Utah did pretty well for eight years,” he said, “and then a student shot himself [in the leg] at Weber State University in 2012, and then in 2016, ’17, and ’18, the last three years consecutively, there’s been a murder with a gun on the campus of the University of Utah, Salt Lake. So their luck’s run out.”

In 2015, during the one-year window the Texas legislature allotted schools to prepare for campus carry, UT Austin hosted two public forums about the implementation. At one of these, I testified that the university should develop a protocol about what to do with guns left behind in bathroom stalls. (Should we bring them to lost and found? Call the police? Put an “out of order” sign on the door?) People laughed. A year later, students left guns in the women’s bathrooms here twice in the same week. According to The Campaign to Keep Guns Off Campus, similar incidents have happened in Georgia and repeatedly in Kansas. And where there are guns, there will be accidents: An Idaho State professor shot himself in the foot during class, and an employee at the University of Colorado in Denver was trying to un-jam her gun when it went off, injuring herself and a coworker.

In addition to dealing with such accidents, campus-carry schools have spent millions adapting their physical infrastructure (installing gun safes, signage and metal detectors, for example), retraining staff, and replacing faculty members lost to attrition. Other instructors have changed their teaching practices by eliminating discussions of sensitive subjects that might raise tempers in the class, or by offering courses exclusively online, or even by holding office hours in bars or churches where guns are prohibited, rather than meet with armed students in their offices.

And then there’s the matter of campus suicide.

The late Allan Schwartz, a professor of clinical psychiatry at the University of Rochester, studied college suicide for the better part of two decades. In 2013, he published an article comparing suicide rates among college students with nonstudents. Using nationally representative data from 2007, he found that, among men age 18-24, the suicide rate was much lower—about half—for those enrolled in college. This, despite that fact that students and nonstudents attempt suicide at roughly the same rate (1.4 percent versus 1.8 percent).

Schwartz considered various parameters that could account for the disparity, and became increasingly convinced that the single most consequential factor was access to guns. Students who lived on campus had a lower risk of suicide than those who lived off campus; those who were enrolled full time had a lower risk than those enrolled part time; those who stayed on campus continuously had a lower risk than those who went home for the weekends, and so on. The more time that students spent in an environment where guns were prohibited, the less likely they were to die by suicide.

Which wasn’t surprising to mental health professionals. Decades of public health research have repeatedly demonstrated that access to guns increases the likelihood of a death by suicide. This is because over 80 percent of people who attempt suicide with a gun die as a result—compared to less than 2 percent of those who use other common means, such as overdosing. And most people who attempt suicide and survive never make another attempt.

“We have no reason to think that the same sort of pattern wouldn’t happen on college campuses that happens off college campuses—the more guns that are present, the higher the rates of suicide,” said Marjorie Sanfilippo, a psychologist at Eckerd College in Florida. To compare suicides at campus-carry schools and schools that prohibit guns, Sanfilippo has begun to survey the directors of college counseling centers across the country. So far, the results are stark: The campus-carry schools had significantly higher rates of both attempted and completed suicides. Sanfilippo acknowledges that her sample size thus far is very modest—just 22 respondents. “Of course, each one represents thousands of students,” she said. She is planning to expand the scope of her research.

Large-scale research projects cost money, though, and when it comes to gun violence, the federal purse strings have been drawn tight for decades. Congress first threatened to defund the Centers for Disease Control in 1996 if it recommended any form of gun control. President Obama issued an executive order in 2013 instructing the CDC to identify priorities for gun violence research, and still the agency demurred. (Obama did get his report, but it was published by the National Research Council and was essentially an analysis of past research—much of it decades old.) Language in last year’s government spending bill softened the threat that gun research could imperil the agency’s budget for injury prevention, but until funds are specifically allocated for gun research, the roadblock remains.

As long as the CDC avoids gun-related research, the institutions best equipped to study the issue are research universities, and they’re about to receive a huge injection of funding for that express purpose. Over the next five years, the National Collaborative for Gun Violence Research plans to distribute up to $50 million from the RAND Corporation, specifically for academic research into gun violence. Sanfilippo is among the many researchers applying for support.

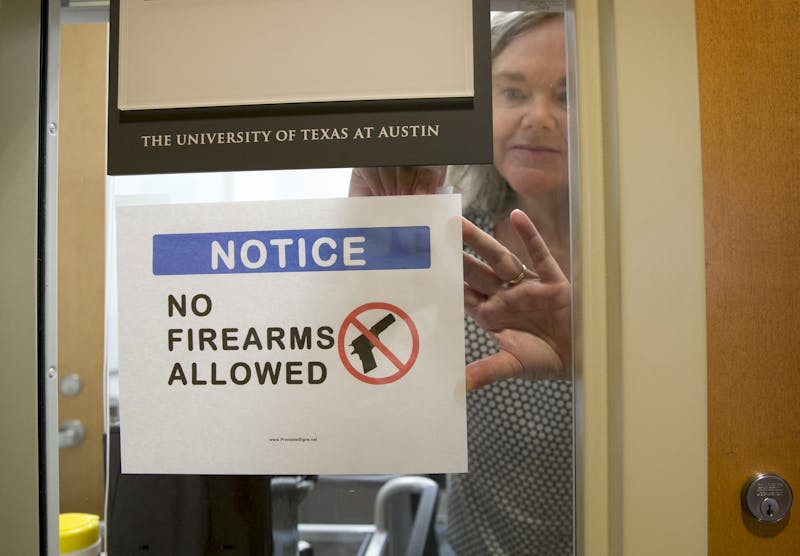

Meanwhile, where campus carry has already been enacted, schools adapt. In 2016, UT Austin implemented a policy that allows faculty and staff members to prohibit guns in our offices. But we’re only permitted to convey this rule verbally; we can’t hang a sign saying, “No guns allowed.” So my colleague George—her nickname, as she resembles the Beatle—came up with a work-around, which required the use of my 9mm Beretta semiautomatic pistol.

Initially, I thought it would only be the two of us at target practice. But by the time I’d secured permission to shoot on private property just outside town, three other women had asked to participate: a UT administrator, a graduate student visiting from another institution, and Ana Lopez, an undergraduate student who co-founded Students Against Campus Carry. She’d become a public face of the resistance to campus carry, profiled in The New York Times and invited to the White House to meet with then–Vice President Joe Biden. She’d also been accused by gun rights advocates of not having the authority to debate campus carry because she didn’t have experience shooting guns. She intended to negate that line of criticism by getting some range time.

As we bumped along a dusty road in the Texas Hill Country, the struts of my Volkswagen hatchback bucking under the weight of five passengers, four guns, and several boxes of ammunition, I was tempted more than once to call it off. Putting a gun in a student’s hands seemed so obviously inappropriate that it needn’t even be mentioned in the university’s handbook of conduct. Or it used to seem that way, anyway.

George had brought her doctoral diploma, also from UT. With binder clips, we fixed it to a target in front of an earthen berm, along a creek lined with Texas live oaks. It hangs now in her office, where visitors ask about the bullet holes between the lines of calligraphy—a prompt to discuss her office gun policy, in lieu of an overt sign.

When Ana’s turn came to shoot, I made her pause a moment as I checked again that the backdrop was clear. I glanced around to confirm everyone was wearing their ear plugs and safety goggles. “Okay,” I finally said. “Disengage the safety.”

What could possibly go wrong?