What was it like to be a queer child in South Carolina during the Great Depression? Guy Davenport, with his incomparable gift for re-creating lost pockets of time, offered one plausible glimpse in his short story “A Gingham Dress,” published in 1990. The scene is a roadside mart, where a hillbilly family is selling homegrown produce out of their car. The father keeps to himself in the front seat while the chatty mother engages with customers, who notice a child wearing a dress. “He’s a caution, ain’t he?” the mom beams. “Going on nine and still won’t wear nothing but a dress and a bonnet. Says he’s a girl, don’t you, Lattimer? He’s as cute as one.”

Both parents are confident, of course, that Lattimer will “grow out of it,” but for now they’re happy to indulge his fancy. This isn’t, Davenport is careful to underscore, any sort of liberal tolerance, but rather the ornery Appalachian instinct to leave well enough alone, an attitude equally compatible with bigotry. “This Roosevelt is something else, ain’t he?” Lattimer’s mom complains. “They say he’s a Jew.” The unanswered question the story raises is: What will happen when Lattimer is older and expected to give up the “phase” of being a girl?

The author had personal reasons to ponder the tightrope walk of sexual minorities raised in a repressive and reactionary culture. Davenport was born in Anderson, South Carolina, in 1927, and grew up being attracted to boys and girls. His parents were loving, but Davenport felt straitjacketed by the pervasive Baptist prudery, which was anti-gay and, more profoundly, anti-body. Davenport remembered being taught in Sunday school “that Jesus’ nudity on the cross was far more painful to him than the nails in his hands and feet.” Davenport was spanked once for uttering the phrase “political cartoon,” which sounded to adult ears like “pantaloon,” a verboten word in his household.

Davenport spent much of his adulthood trying to deprogram himself from his South Carolina indoctrination. Although slow in learning how to read, Davenport quickly became a star pupil, excelling in English and the classics at Duke University and then, via a Rhodes Scholarship, at Oxford, where he became the first student at that school to write a thesis on James Joyce. In his Oxford years, he became enthralled by the poetry of Ezra Pound, the subject of his doctoral thesis at Harvard. The classics and modernism were linked in Davenport’s mind (he studied Pound’s use of Greek myth), and both offered an alternative to the provincialism and puritanism in which he’d grown up.

Yet even as he advanced academically, Davenport displayed inwardly sabotaging qualities, a shyness and self-doubting diffidence that often led him to abandon projects or restrict his publication to small and sometimes vanity outlets. As an undergraduate at Duke, he wrote stories and a novel that amazed his peers and teachers, including his classmate William Styron. “I can only look upon Guy Davenport with the greatest awe and respect,” the future author of Sophie’s Choice wrote to a teacher in 1947, after reading the manuscript of Davenport’s novel. Styron predicted that “within the next decade or so,” Davenport would become “one of America’s best writers.” In fact, Davenport gave up on his novel and wouldn’t write fiction again for more than two decades, bringing out his first story collection in 1974. Similarly, Davenport wouldn’t publish his Harvard thesis for 22 years after its 1961 completion, despite the urging of fellow scholars and the request of publishers. Some of his most heartfelt essays and stories were portraits of writers prone to self-silencing renunciation: Kafka, Walser, Wittgenstein.

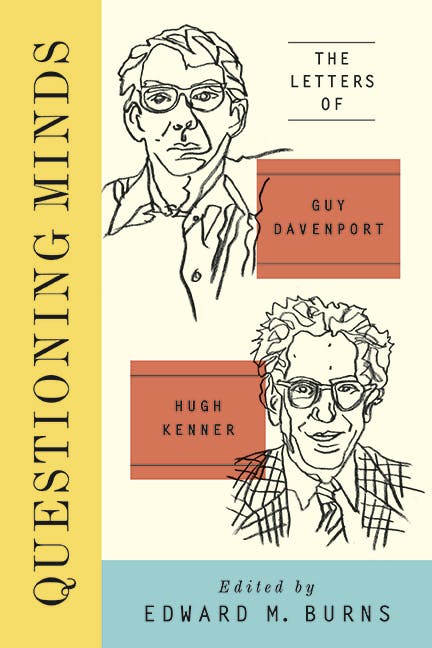

Left to his own devices, Davenport could have made do as a scholarly hermit, content to read books, fill up his notebooks, teach a few students, and go camping with his lovers. Yet Davenport avoided this fate and became a prolific essayist, illustrator, translator, poet, fiction writer. He owed this transformation largely to one man, the literary critic Hugh Kenner. The intense friendship between the two writers, a consequential union that remade them both, can now be charted, thanks to the publication of a hefty and sturdy two-volume set, Questioning Minds: The Letters of Guy Davenport and Hugh Kenner, edited by Edward M. Burns. The volumes make clear that it was Kenner who coaxed Davenport into print, while Davenport was the source of many of the key ideas, and even some of the words, of Kenner’s 1971 masterpiece, The Pound Era, one of the greatest works of literary criticism of the last century.

More than any other critics, Kenner and Davenport defined modernism as a cohesive literary renaissance, represented by the shared aesthetic inventiveness of a group of writers—chiefly Pound, T.S. Eliot, James Joyce, Wyndham Lewis, and Marianne Moore—who wanted to revitalize our links to the past. Modernism, as Kenner and Davenport showed in numerous studies, answered the radical discontinuity created by technology by fusing linguistic play with classical themes; for them, Joyce’s fusion of a Dublin everyman with a Homeric hero was an emblematic act. “The gods have never left us,” Kenner boldly argued in The Pound Era. “Nothing we know the mind to have known has ever left us. Quickened by hints, the mind can know it again, and make it new.” This view of modernism as both restorative and radical—as the “renaissance of the archaic,” in Davenport’s words—remains our most persuasive and fruitful interpretation of many of the preeminent novels and poems of the last century.

Totaling more than 2,000 pages and more than 900,000 words, bringing together roughly 1,000 letters from 1958 to 2000, Questioning Minds is a monument to the strange and wonderful relationship of two oddballs uniting to make an odd couple. If you wanted to pitch Questioning Minds to Hollywood, it would undoubtedly be as a buddy comedy: the unlikely story of how a randy bisexual utopian teamed up with a crusty right-wing Roman Catholic to solve the mysteries of modernism.

Like Davenport, Hugh Kenner was a polyglot polymath who hailed from the hinterland, in his case Canada. Born in 1923, Kenner grew up in the sleepy town of Peterborough, Ontario, the son of a classics teacher. A bout of influenza at age five left him mostly deaf, leading to a lonely, bookish childhood. When Kenner came to study at the University of Toronto in the 1940s, he discovered that he lived in a country where literary modernism was literally held under lock and key. Joyce’s Ulysses was banned in Canada (as were works by Balzac and D.H. Lawrence). Kenner’s university had a copy, but undergraduates could only get their hands on it if they had two letters attesting to their moral and physical soundness, one from a religious figure and one from a doctor. Lacking a medic to vouch for his purity, Kenner became one of the few to read Finnegans Wake before Ulysses.

Toronto gave Kenner his first great mentor: Marshall McLuhan, then an obscure professor incubating the media studies that would make him famous in the 1960s. McLuhan and Kenner shared a worldview that combined conservative politics with an enthusiasm for experimental literature. They saw the great modernist works as a balm for the alienation of modernity—like a sip of brandy that could cure a hangover. This perspective had a religious component: McLuhan was a Catholic convert, and Kenner a self-described Catholic fellow traveler who would join the Church in 1964. Their turn toward Catholicism occurred as the Church, on the cusp of Vatican II, was gingerly making peace with modernity.

It was in McLuhan’s company in 1948 that Kenner met Ezra Pound, then incarcerated for alleged insanity in St. Elizabeths Hospital in Washington, D.C. Pound, who had been the great impresario of modernism, writing its manifestos and closely nurturing the work of T.S. Eliot and many other writers, was then at the low point of his reputation, widely derided as a lunatic, a traitor, an anti-Semite, and a fascist. There was truth to most of these accusations: Pound had spent the war years making a series of deranged radio broadcasts, denouncing Jews, democracy, and the United States while also praising Mussolini’s regime. But Kenner, who had a lifelong contrarian tendency to try and find the nugget of wisdom in cranks, fell under the spell of Pound’s poetry and quickly became his leading advocate.

Unlike Davenport, Kenner was never too shy to publish. When he and Davenport first met at a Columbia University panel discussion in 1953, Kenner already had two books under his belt (on G.K. Chesterton and Pound) and two more (on Wyndham Lewis and James Joyce) on the way. By 1958, the year in which Questioning Minds begins, Kenner, although only four years Davenport’s senior, was much more firmly established in the literary world. Davenport was still a graduate student while Kenner was ensconced as head of the English Department at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and an important, if controversial, voice in literary criticism.

Critics, especially liberal and leftist ones, treated the early Kenner with wariness. His intelligence was undeniable, but the anti-liberal undercurrent of his work rankled. Writing in Partisan Review in 1954, Irving Howe sneered, “When a charlatan like Wyndham Lewis is revived and praised for his wisdom, it is done, predictably, by a Hugh Kenner in The Hudson Review.” Stung by this hostility, Kenner cast about for allies. He found one in the form of William F. Buckley, whom he met at a party in 1957. Buckley and Kenner became tight friends, with Kenner emerging as a frequent contributor to Buckley’s National Review.

As a conservative modernist, Kenner occupied a precarious position: Liberals distrusted him for his conservatism, conservatives for his modernism. During his tenure as National Review’s poetry editor, Kenner had to fend off readers upset by the vers libre and left-wing politics of William Carlos Williams. “National Review has some of the dumbest readers in the world,” Kenner lamented. The magazine, Kenner noted, had a “stodgy tendency to equate conservatism with resistance-to-all-change-of-preconceptions.” On the flip side, Denise Levertov withdrew a poem from National Review when she discovered the magazine’s politics.

In his search for allies, Kenner set his sights on Davenport. His early letters work toward the twin goals of recruiting Davenport to join him at the University of California and to write for National Review. Davenport never took the job—he settled for the University of Kentucky, nearer his South Carolina family—but he did become one of the most prolific National Review essayists, even though he did not share the magazine’s politics. (Davenport always voted Democratic, until Bill Clinton drove him into the arms of Ralph Nader in 1996; in his fiction, he took imaginative pleasure in exploring the ideas of the utopian socialist Charles Fourier.)

Davenport the public writer was born in these essays. As National Review’s jack-of-all-trades, he tackled everything from Tarzan to Tchelitchew, from Toulouse-Lautrec to Tolkien. This National Review writing formed the seedbed for The Geography of the Imagination (1981), the much-cherished Davenport collection that was a National Book Awards finalist in 1982. With characteristic slyness, Davenport enjoyed sneaking in praise of same-sex love and androgyny to the pages of William F. Buckley’s magazine. (Though National Review wasn’t always the most congenial home for Davenport’s thoughts: In 1970, he wrote a review tracing back Hemingway’s prose to Walter Pater’s aestheticism. This was an idea Kenner would return to in his own work. But a National Review staffer scoffed and added a note at the beginning of the issue complaining, “He’s comparing Hemingway to that purple faggot Walter Pater!”)

The real drama of the Davenport-Kenner correspondence is to see two prickly, isolated minds start to flower in the warmth of mutual understanding. Time and again, Kenner can be seen prodding Davenport to turn his private passions into public art. Charmed by Davenport’s Max Beerbohm–style cartoons of writers, Kenner recruits him to illustrate two of his critical books, The Stoic Comedians (1962) and The Counterfeiters (1968). Impressed by ad hoc translations Davenport supplied in the letters, Kenner eggs him on to publish his quirky, sharp-worded translations of Archilochus and Sappho. “Curious as it may sound, you are the first person who has ever encouraged me in my work,” Davenport wrote Kenner in 1962.

Davenport, for his part, turned Kenner into a much more daring writer. Kenner’s pre-Davenport books are assertive but still operate under the conventions of normal scholarship. Having Davenport as a sympathetic reader, Kenner let loose his ambition to write books about modernism that mimic modernist literary techniques: They are nonlinear, boldly jumping from topic to topic, juxtaposing disparate scenes with the expectation that the reader will fill in the gaps. Kenner modeled The Counterfeiters and The Pound Era on Pound’s Cantos, a fragmented epic that combines lyrical observation and radical juxtapositions with historical sweep. The Counterfeiters is a juggling act of a book that, under the umbrella of mechanical reproduction, links together Gulliver’s Travels, the early computer designs of Charles Babbage, the impact of empiricism on bad poetry, Jorge Luis Borges, the evolution of Latin abstract nouns, Buster Keaton, Andy Warhol, and Alan Turing’s speculations on artificial intelligence (among many other topics). The sum is the funniest book of literary criticism ever written.

One of the revelations of Questioning Minds is that Kenner freely mined Davenport’s correspondence for ideas and phrases. The first chapter of The Pound Era presents a defense of Pound’s translation of Sappho. Reading the letters, you can see how Kenner’s book reworks Davenport’s ad hoc explanation of the translation to Kenner. Davenport’s lessons on working with torn papyrus lead to a key insight of The Pound Era, that the modernists used fragments the way archaeologists do, not as ruins to be mourned but as rich sources of knowledge.

In 1963, Davenport visited Ezra Pound’s childhood town, Wyncote, Pennsylvania, and gathered stories about the last visit the poet ever made there. Davenport wrote this up in a beautiful letter, which, distilled, became the last paragraph of The Pound Era. None of this amounts to plagiarism. Not only did these borrowings have Davenport’s approval, but the two men had also by then formed a mind-meld that made it impossible to separate out their thoughts. Asked by Davenport if he could write on topics Kenner had touched, Kenner responded, “There is no property in the things of the mind.” Earlier, Kenner’s friendship with McLuhan foundered when the media sage unjustly accused his disciple of stealing his ideas. In fact, Kenner had written up ideas developed together in conversation, with a lucidity McLuhan was incapable of. With Davenport, Kenner found a more congenial collaborator.

One of the enthusiasms Kenner and Davenport shared in the 1960s was for the architect and futurist Buckminster Fuller, who popularized the idea of synergy and coined the term “synergetics.” The word has now unfortunately passed into management consultant cant, but the friendship of Kenner and Davenport illustrates a truly remarkable kind of relationship. Writing to Davenport in 1963, Kenner tried out an idea, “I am coming to think that the key to the Pound Era is the discovery of synergy.” Modernism, by this account, was a vortex, a joining together of talent that created something greater than the sum of its parts. Hence Kenner’s fascination with the synergistic event or happy collaboration: Pound’s extensive editing of The Waste Land, Pound’s use of Ernest Fenollosa’s notes to reinvigorate the translation of Chinese poetry, even something as lowly as Pound buying the impecunious Joyce a new pair of shoes.

While Davenport is chatty and revealing from the earliest letters, the tone of Kenner’s correspondence goes through an important change as he grapples with the cancer of his first wife, Mary-Jo Kenner, in 1963 and 1964. Prior to that crisis, Kenner tended to be aloof and professional. During those years, Kenner was on a leave to teach at the University of Virginia, which allowed Davenport to make visits, and he became a source of comfort for the family. In his letters, Kenner opens up as never before, writing about such intimate matters as his decision, shared by his dying wife, to convert to Catholicism. After Mary-Jo Kenner died in December 1964, Davenport helped Kenner look after his five children during the funeral. John Kenner, who was ten at the time, told me, “Guy Davenport once spent a weekend drawing with me, distracting me from my grief over my mother’s death.”

After Davenport returned home from the funeral, Kenner wrote, “How wonderful to have you around: especially as your dealings and doings with the children have helped me to realize what an achievement that family is: and it is her achievement. They are, singly and collectively, her memorial. Everything perhaps perishes but tradition.” With these words, Kenner is articulating the central theme of The Pound Era: the power of a living and creative tradition as a stave against loss. The Pound Era would be dedicated to the memory of Mary-Jo Kenner. Kenner remarried the following year, with Davenport as part of the groom’s party and William F. Buckley as best man.

Taking to heart Ezra Pound’s injunction to “make it new,” Kenner and Davenport wrote letters alive with fresh language. Here is Davenport’s account of riding with a student on the back seat of a motorcycle on the way to New York’s Museum of Modern Art (with a nod to Davenport’s military service):

With knees kissing, now this, now that entire flank of a taxi, we threaded fifty blocks of traffic. Only in mountain climbing or in firing 8” Howitzers with a cold breech does one feel as helpless: life means nothing and everything. But I had a captive audience to lecture to, explaining the whole damn museum in three hours.

Here he is describing Buckminster Fuller, briefly comparing him to a student named Robert Gallway (given the epithet Erewhonian, from Samuel Butler’s novel Erewhon):

He’s a dwarf, with a worker’s hands, all callouses and squared fingers. He carries an ear trumpet, of green plastic, with world series 1965 printed on it. His smile is golden and frequent; the man’s temperament is angelic, and his energy is just a touch more than that of the Erewhonian Gallway (champeen runner, footballeur, and swimmer). One leg is shorter than the other, and the prescription shoe worn to correct the imbalance comes from a country doctor deep in the wilderness of Maine.

And here is Kenner trying to comprehend the cancer that would soon kill his first wife: “We are all dying, but at different rates.” Questioning Minds is chock-full of countless sentences of like quality: chewy, savory, nutritious.

Some of the more pernicious sides of Pound, however, also left a mark. In his letters, Pound liked to refer to languages with ethnic slurs (referring to Italian, for instance, as “wop”). Both Kenner and Davenport echo their master in this juvenile habit, a failure of the humanism that is the hallmark of their best work. It also mirrors one of the few significant failures of The Pound Era, the lack of full reckoning with Pound’s anti- Semitism. Ezra Pound was a cyclops: a giant cursed with tunnel vision and easily blinded. Kenner and Davenport, frequently brilliant and at times blinkered, also belonged to the tribe of one-eyed geniuses.

It’s hard to know what Kenner, as a traditionalist Catholic, made of Davenport’s bisexuality. In The Stoic Comedians, Kenner made a strange offhand jibe about “sodomy.” In National Review, Kenner aligned himself with the socially conservative wing of the magazine, praising Joseph Sobran’s book of essays against abortion, feminism, and gay rights. Davenport was formed in the pre-Stonewall world and wasn’t public about his sexuality. But he didn’t quite hide it either. It was more of an open secret. When he took up writing stories again in 1969, his work was unabashedly homoerotic, often dealing with the sexual awakening of queer boys. In his letters to Kenner, Davenport doesn’t identify his boyfriends as such but certainly speaks of them with the same openhearted warmth that he uses for his girlfriends. And Davenport also wrote to Kenner about the love life of his gay friends, such as the poets Jonathan Williams and Ronald Johnson.

Kenner and Davenport never stopped being friends, but starting around 1975 their relationship cools. Letters become less frequent and more perfunctory. “We, you and I, are beginning to drift out of synchronicity,” Davenport wrote Kenner in 1977. In his introduction to Questioning Minds, Burns speculates that “perhaps as Davenport’s homoerotic interests emerged in his fictions and in his drawings Kenner withdrew from contact with him.” Arguing against this is Kenner’s continued praise of Davenport’s fiction; in 1996, Kenner wrote a rave review of Davenport’s last story collection, The Cardiff Team, (even commending one homoerotic story for its “sexiness”) as well as an affectionate introduction to Guy Davenport: A Descriptive Bibliography, 1947–1995.

Kenner’s personal coolness and silence could perhaps have resulted from the fact that he and Davenport had just gone on separate career paths, with Davenport increasingly focused on creative work that precluded scholarly collaboration. Or it could have been a matter of aging. William F. Buckley also felt that in his last few years Kenner was becoming more distant. Whatever the cause of the diminished friendship, Davenport was left baffled and hurt. “From Hugh I’ve heard nothing,” Davenport complained to the publisher James Laughlin in 1990. “We used to be the best of friends.”

In 2002, Kenner wrote his last letter to Davenport. It reads in part: “We’ve been separated for too long; here I am in the final months of my 79th year.” Hugh Kenner died the following year; 14 months later, so did Guy Davenport. The penultimate sentence of The Pound Era is a quote from The Cantos: “Shall two know the same in their knowing?” It’s followed by a sentence first written by Guy Davenport in a 1963 letter, which Kenner got permission to appropriate: “Thought is a labyrinth.”