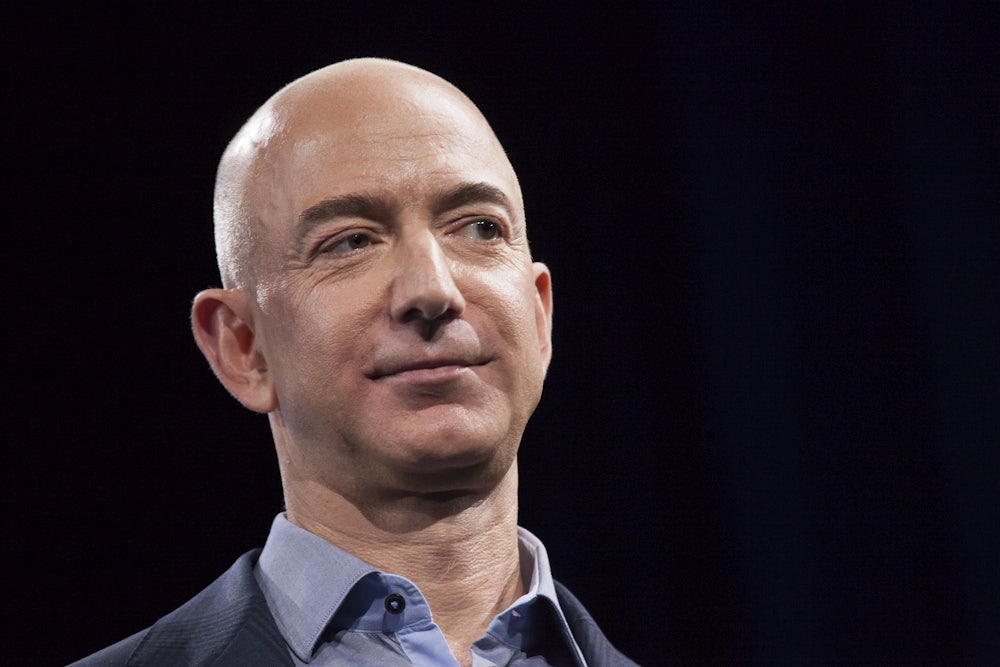

The world’s richest man had a week unlike any in his life. Last Thursday, in a long post on the website Medium, Jeff Bezos accused the National Enquirer of extorting him with compromising photos. The tabloid had published lurid texts that proved that the Amazon founder and CEO, whose divorce from his wife of 25 years was already pending, was having an affair. His 2,200-word gambit didn’t just neutralize the alleged scheme; it brought Bezos seemingly universal adulation. “I think he single-handedly changed the first line of his obituary, from Silicon Valley billionaire to First Amendment defender,” Poynter vice president Kelly McBride told CNN’s Brian Stelter. “And that’s quite remarkable.’’

The Washington Post, which Bezos owns, didn’t go quite that far, but its editorial board lauded him for choosing “to expose what lies behind the National Enquirer’s claim to be a practitioner of newsgathering.... Mr. Bezos’s action has exposed the truth: that its business lies not in honest journalism but in sleazy tactics and dirty tricks.”

Since purchasing Post for $250 million in 2013, Bezos has become one of the most important figures in journalism. Never particularly interested in the industry before, he has spent hundreds of millions of dollars revitalizing the paper, which now employs around 900 journalists, with bureaus around the world. This has brought him into conflict with President Trump, who repeatedly threatens Amazon over what he believes is unfair coverage in the Post. But the Post, and the political influence it has brought Bezos, has also created a crucial moat for him and for Amazon at a time when Congress is scrutinizing the company’s business practices and the public’s opinion of Big Tech is souring.

Despite Bezos’s victory over the National Enquirer—and by extension the president, who enjoys a mutually beneficial relationship with the paper’s publisher, David Pecker—there’s growing tension between Bezos’s role as the savior of one of America’s most important news organizations and his role overseeing an anti-democratic corporate behemoth. Or there should be, anyway. His missive against the Enquirer may have been righteous, but someone with Bezos’s enormous economic and political power—especially given Amazon’s myriad controversies—deserves much more skepticism and much less hero worship.

As Bezos was being applauded for his takedown of the Enquirer, Amazon was stepping up its fight with lawmakers in New York City, who had questioned the billions of dollars in tax breaks and incentives that the city and state had offered to one of the world’s most successful companies. On Friday, less than 24 hours after Bezos’s Medium post went live, the Post reported that Amazon was considering pulling out of New York altogether if skeptical members of the city council and state Senate didn’t get on board. “No specific plans to abandon New York have been made,” the Post reported. “And it is possible that Amazon would try to use a threat to withdraw to put pressure on New York officials.”

It was, as the Seattle Times’ Danny Westneat noted, a different kind of extortion scheme. “Sure it may seem a little mobbed up when they threaten to shoot your economy, even as they’re also showing up at a meeting to supposedly ‘negotiate,’” Westneat wrote. “It’s just business to them.” That same week, Amazon signed a deal with Virginia that would grant the company generous tax breaks and incentives—and would require the state to give a “heads up” to the company if anyone submitted Freedom of Information Act requests about the company. That’s not exactly the kind of behavior you would expect from a “First Amendment defender.”

This is how Amazon does business, as Seattle knows all too well. Last fall, Amazon recently halted construction of new buildings there—and threatened to leave the city altogether—in protest of a new tax on large companies to fund affordable housing. The Seattle area has the third-largest homeless population in the country, behind only New York and Los Angeles, according to federal statistics. But Amazon’s threats got the city’s attention. “That really changed things overnight,” Katie Wilson, of Seattle’s Transit Riders Union, told The Atlantic. “People got scared.” Westnead, in his column, cast it as another mafioso move: “Nice economy you’ve got there, Seattle. Shame if something happened to it.” The city council repealed the tax less than a month after passing it unanimously.

Amazon’s ruthless behavior isn’t limited to its dealings with city and state governments. The company began as an online bookstore which ruthlessly undercut publishers; Bezos reportedly instructed the company to “approach these small publishers the way a cheetah would pursue a sickly gazelle.” While definitive data doesn’t exist, Amazon is routinely blamed for the downturn in bookstores over the past two decades and the decline in author earnings. For much of its existence, the company skimped on sales tax, which it only recently began paying in all 50 states. Over the last several years, there have been a series of investigations into the poor treatment of the company’s warehouse and delivery workers, who often endure long shifts in deplorable conditions—sometimes literally working themselves to death.

And yet, Amazon has proved largely immune to this negative press. Like other Big Tech companies, notably Google, it has stayed popular with the general public, even as it has become one of the most powerful entities on the planet. Polling released last fall found that Amazon was more trusted by Americans than the government and the press—and that, for Democrats, it was the most trusted institution in the entire country. The low cost and convenience of Amazon surely has a lot to do with that, but Bezos’s ownership of The Washington Post likely has helped, particularly with elites.

But Amazon’s immunity is unlikely to last. People are slowly growing more skeptical of the Silicon Valley giants. In the aftermath of Facebook’s Cambridge Analytica scandal, the favorability of Amazon—and other tech companies—plunged, a sign that increased scrutiny of one tech company can adversely impact the others. It ended the year both popular and trusted, but the earlier dip suggests that sustained scrutiny of the tech giant could lead to lasting damage.

The biggest threat to Amazon’s reputation is itself. As the company expands its operations to Washington, D.C, and New York City, more Americans will experience firsthand what Seattle residents have lived with for years—and those Americans happen to live in the two biggest journalism markets in the country. The ensuing battles with residents, activists, and politicians, as well as stories of worker trauma, will gain significantly more national coverage than before.

At the same time, there is an increasing bipartisan consensus that tech companies like Amazon—which has enormous economic power in a number of retail sectors—have grown too large and too powerful. The public testimony of Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg and Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey last year was just the beginning of a larger project that will draw greater attention to the misdeeds of every large technological company. Several Democratic presidential candidates, notably Elizabeth Warren and Amy Klobuchar, have called for increased scrutiny and regulation of tech giants like Amazon.

Bezos may see the Post and his other extracurricular projects as armor for these fights. Citing the paper’s grandiloquent motto, “Democracy Dies in Darkness,” he has made the case that owning the Post is a higher civic calling. “Certain institutions have a very important role in making sure there is light, and I think The Washington Post has a seat, an important seat to do that, because we happen to be located here in the capital city of the United States of America,” Bezos told Post editor Marty Baron back in 2016. In last week’s Medium post, he wrote, “The Post is a critical institution with a critical mission. My stewardship of the Post and my support of its mission, which will remain unswerving, is something I will be most proud of when I’m 90 and reviewing my life...”

But Bezos did not become one of the wealthiest people in the world out of a commitment to civic engagement. On the contrary, in building Amazon into a $1 trillion company, he has often worked against the public interest. He is a cunning and ruthless man, and there’s every reason to believe he bought the Post for strategic, not civic reasons: to wield greater power and influence in Washington, where Amazon’s lobbying spending has skyrocketed in the years that Bezos has owned the paper.

Bezos’s Medium post, much like his purchase of the Post, has been portrayed as daring when in fact it was calculating. The essay was simply the wisest course of action for him, given the situation. American Media Inc, the Enquirer’s parent company, wanted to neutralize the Post’s coverage of its relationship with Trump, so it demanded that Bezos release a statement that he has “no knowledge or basis for suggesting that AMI’s coverage was politically motivated or influenced by political forces.” Bezos knew that he would forever lose the loyalty of the Post staff with such a statement. He also knew that the compromising photos might leak anyway. But above all, perhaps, he knew that he would receive near-unanimous praise from the Fourth Estate, including the large plot that he owns.