It’s hard to find anyone who will admit to it now, but when the CenterPoint Intermodal freight terminal opened in 2002, people in Elwood, Illinois, were excited. The plan was simple: shipping containers, arriving by train from the country’s major ports, were offloaded onto trucks at the facility, then driven to warehouses scattered about the area, where they were emptied, their contents stored. From there, those products—merchandise for Wal-Mart, Target, and Home Depot—were loaded into semis, and trucked to stores all over the country. Goods in, goods out. The arrangement was supposed to produce a windfall for Elwood and its 2,200 residents, giving them access to the highly lucrative logistics and warehousing industry. “People thought it was the greatest thing,” said Delilah Legrett, an Elwood native.

In addition to bringing more containers and warehouses, the Intermodal promised to foster vital growth and development. In a town without sidewalks, grand pronouncements were made in the run-up to the Intermodal’s debut. There would soon be hotels, restaurants, a grocery store; flower shops and bars would follow. Property values would surge, schools would be flush with cash. Most importantly, there would be great, high-paying jobs, the kind that could sustain a community devastated by farm failures and the wide-scale deindustrialization of the Midwest. In Will County, of which Elwood is part, the unemployment rate soared to a high of 18 percent in the 1980s, before gradually coming closer to the national average in the 1990s. In Joliet, the nearest urban center, it hit 27 percent in 1981.

An opportunity as great as the Intermodal came with a cost. First, to help seal the deal, the town had to offer the developer, CenterPoint, a sweetener: total tax abatement for two decades, until 2022. Second, the town would have to put up with an influx of truck traffic. No matter: With large-scale manufacturing shifting to the Pacific Rim at the turn of the millennium, the warehousing and logistics industry offered a chance to get back in the good graces of a global economy that had, for decades, turned its back on rural America. Elwood yoked its hopes to warehousing, which would carry the town to the forefront of America’s new consumer economy.

In a few short years after the Intermodal opened, Elwood became the largest inland port in North America. Billions of dollars in goods flowed through the area annually. The world’s most profitable retailers flocked to this stretch of barren country, while the headline unemployment rate plunged. Wal-Mart set up three warehouses in Will County alone, including its two largest national facilities, both located in Elwood. Samsung, Target, Home Depot, IKEA, and others all moved in. Will County is now home to some 300 warehouses. A region once known for its soybeans and cornfields was boxed up with gray facilities, some as large as a million square feet, like some enormous, horizontal equivalent of a game of Tetris.

Fifteen years before Amazon’s HQ2 horserace, Elwood had won the retail lottery. “Nobody envisioned what we have out here,” said Jerry Heinrich, who sat on the board of the planning commission that first apportioned the land for development in the mid-1990s. “It was never anticipated that every major business entity would end up in the area.”

But this corporate valhalla turned out to be hell for the community, which suffered a concentrated dose of the indignities and disappointments of late capitalism in the 21st century. Instead of abundant full-time work, a regime of partial, precarious employment set in. Temp agencies flourished, but no restaurants, hotels, or grocery stores ever came, save for the recent addition of a dollar store. Tens of thousands of semis rumbled through Will County every day, wreaking havoc on the infrastructure. And as the town of Elwood scrambled to pave its potholes, its inability to collect taxes from the facilities plunged it into more than $30 million in debt.

And that was before Big Tech rolled in. Just four years ago Amazon didn’t even have one facility in the region; now, with five fulfillment centers, it’s the county’s largest employer. Growth, once arithmetic, became exponential. Plans were made to build a new facility, this one bigger than the original Intermodal, with room for some 35 million additional square feet of industrial space.

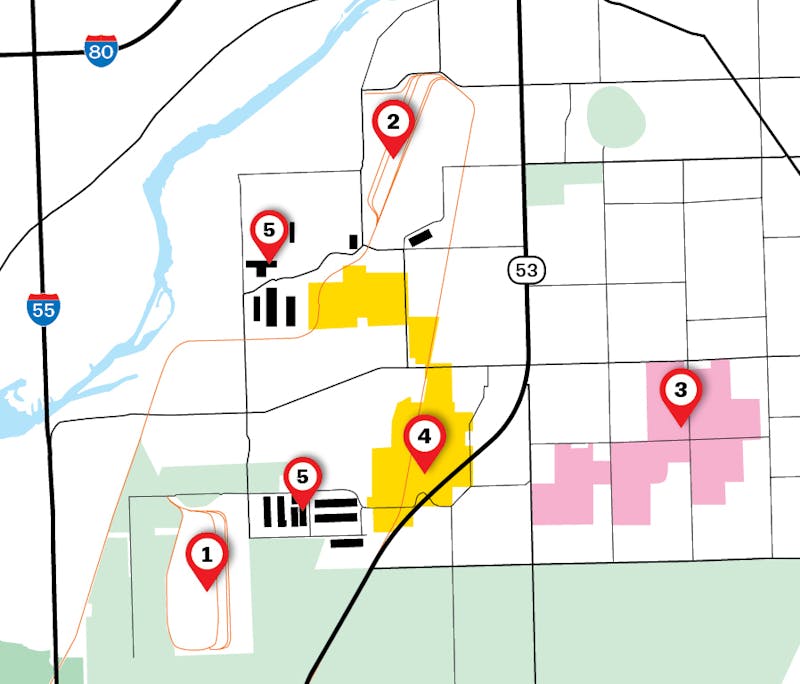

NorthPoint, a Kansas City-based developer, began quietly buying up the necessary parcels of land. In June 2017, a map of the proposed project was leaked on Facebook. Some residents, like Legrett, saw their homes up against a new industrial park. “Some of my friends’ houses had buildings on top of them,” she said. Others fared worse. Julie Baum-Coldwater spotted her family’s farm smack in the middle of the facility. “When I saw the plan I just freaked,” she told me.

The town mobilized to stop the new warehousing development. Signs reading “Just Say No to NorthPoint” and “No More Trucks” sprouted on front lawns. Doors were knocked on. By the time the Elwood planning and zoning commission convened in December 2017 to vote on whether to recommend the facility to the town’s board for approval, tensions were high. Some 400 attendees crammed in the Elwood Village hall, with more still turned away. The meeting ran long, as did a second one, then a third, which had to be scheduled at the gymnasium at Elwood School, with bleachers packed and folding chairs on the basketball court. An overflow room with a livestream was set up in the cafeteria. Altogether, 800 people turned up, in the dead of winter, more than a third of the town’s population.

Nearly 100 speakers commented publicly; only four were in favor. Amid tears and a chorus of boos, the committee voted 3-to-1 to approve the new facility. If the people of Elwood wanted to save themselves and their town, they would have to fight for it.

In Elwood, geography is destiny. For homesteaders and farmers heading west in the 19th century, the flat terrain and quality soil made the region a major draw. “This area is kind of like a fertile crescent,” said Baum-Coldwater, whose 540-acre farm has been worked by her family for 160 years and counting. The Coldwaters are one of many multi-generational farming families in the area, producing soybean seeds, primarily, as well as corn and oats. From the front porch, they can still see the original residence Julie’s husband’s great-great-grandfather built in 1858, as well as the houses his grandmother and grandfather each grew up in, before they married.

Even the most thorough tour of Elwood doesn’t last long. The town’s nucleus sits on the west side of a highway, where a small strip mall, home to Silver Dollar restaurant and the Dollar Tree, leads to a handful of municipal buildings and a few blocks of housing. That denser development quickly gives way to a broad campestral swath, with the occasional farmhouse identifiable only because the area is so flat.

But it wasn’t topsoil that caught the eye of industry—it was Elwood’s serendipitous proximity to the country’s major infrastructure. Six class-1 railroads and four interstate highways pass through the region, which is situated a day’s drive from a full 60 percent of the country. Chicago is some 40 miles northeast as the crow flies.

For much of the 20th century, Elwood sat in the shadow of the Joliet Arsenal, an Army facility built in 1940 that churned out bombs and TNT to feed the American war machine from World War II through the Cold War. But once the Vietnam War ended, its utility subsided. In 1976, the facility was shuttered.

What to do with 23,500 idle acres became the subject of great debate. Mining and asphalt plants were suggested; a coal-fired power plant was proposed; so, too, was a new landfill. The passage of the Illinois Land Conservation Act in 1996 enshrined a solution. Nineteen thousand acres were converted into protected prairie land, where 73 head of bison currently roam. The Abraham Lincoln National Cemetery, the country’s second-largest military cemetery, was also established. That left 2,000-odd remaining acres, officially a Superfund site, too spoiled to farm. This remaining tract was zoned for light industry. For Jerry and Connie Heinrich, who headed up the effort to preserve the region’s prairies, it was the best of all possible outcomes, considering the alternatives. “The Greens were excited,” Jerry told me.

Soon after, CenterPoint came through with its proposal for the Intermodal. The deal sounded good. CenterPoint, which is now owned by CalPers, the California public sector pension group, bought the land for an undisclosed amount. In addition to the tax abatement, Elwood, then shy of 1,700 people in total, agreed to build out a big-league water and sewer system for the facility, and extend municipal fire and police protection. In anticipation of the population and economic growth to come, they even built a new town hall, a tan, multi-story structure complete with a backyard pond and a fountain, referred to playfully as the Taj Ma-hall.

When the facility opened in 2002, it was centered around the Burlington North Santa Fe (BNSF) railroad, which subsequently bought the loading zone. Warehouses were constructed nearby. The plan proved to be an immediate success: An ambitious forecast claimed that within eight to ten years the facility would see 500,000 containers annually; that threshold was surpassed in four.

That was enough to attract the eye of a notable investor: Warren Buffett, who made a pilgrimage to little Elwood in the late 2000s to survey the facility. According to one version of local legend, Buffett took in the scene of BNSF trains unloading containers onto trucks, and the trucks casting off into all corners of the United States, and declared, “This is the future of logistics.” On November 3, 2009, Buffett bought BNSF in its entirety—and with it, the Intermodal.

After that, it was on. The success of the BNSF Intermodal, no doubt aided by the star power of Buffett, inspired railroad rival Union Pacific to set up a smaller, copycat facility across the street. The country’s richest families moved in, at least in name. In addition to two Wal-Mart warehouses, each between 1.6 million and 1.8 million square feet, Elwood got a Walton Drive, named after the Walton dynasty that owns the big-box chain.

For Delilah Legrett, a lifelong resident of the area and mother of four, the drawbacks came quickly—starting with all the trucks. Property values were supposed to skyrocket, but Legrett didn’t even feel comfortable letting her children play in front of their house with the semis hurtling through the town, sometimes as fast as 40 or 50 miles per hour. With toddlers, the persistent diesel exhaust was concerning. “We had problems with our baby monitor because it would pick up frequencies” from passing truck radios and warehouse dispatchers, she told me.

According to the Will County Center for Economic Development, at least 25,000 tractor trailers a day come through the Intermodals. That amounts to three million containers annually, carrying $65 billion worth of goods. A staggering $623 billion worth of freight traversed Will County infrastructure in 2015 alone, roughly equivalent to 3.5 percent of the U.S.’s total GDP.

For Paul Buss, the 77-year-old highway commissioner of Jackson Township, the unincorporated land that sits to Elwood’s north, the trucks unleashed the chaos of the global supply chain on what was once a provincial post. “When I started, all these roads were dirt,” he told me as we drove around in his raised red Ford pickup. Once, a few slow tractors on the highway constituted a traffic jam. Now, the nearby interstates—the I-80 and the I-55—are swollen with semis at all hours of the day, while cataracts of trucks have spilled onto local highways and country roads. Potholes abound, and serpentine traffic jams have roiled residents. Trucks have backed over gravestones at the local cemetery after taking wrong turns. In 2016, a train derailed and hit a semi, throwing debris across the grounds of an elementary school, which was subsequently shuttered permanently for safety reasons. On the day I arrived, there were three accidents alone on I-80.

The inconvenience of a gridlocked infrastructure pales in comparison to the horror of increasingly commonplace traffic fatalities. In recent years, a pregnant mother was killed on I-80, and an eight-year-old girl was killed off highway 53. In 2014, a truck driver fell asleep at the wheel and killed five people on I-55. After a fatal accident outside the two newest Amazon fulfillment centers, cops had to take over traffic control during the afternoon shift change. “You think it would be a big news story,” said Legrett, “but it happens all of the time.”

Buss is responsible for the country and local roads around highway 53, a ribbon of four narrow lanes that connects the interstates with Elwood. Sometimes all four lanes will be occupied by baby blue Amazon trailers featuring the company’s signature curved arrow, four immense white smiles all in momentary alignment. The facilities run 24 hours a day, and the three shift changes—morning, afternoon, and just before midnight—are particularly harried. Backups of hundreds of cars and semis are frequent. Municipalities have struggled to maintain the roads—one stretch of 53 was repaved three times last summer alone.

The turmoil has only been exacerbated by changes in the trucking industry, which has pivoted to an owner-operator model, relying on independent contractors over full-time employees. Oftentimes, truckers are paid per load—$50 to $70 to pick up a container from the Intermodal and drop it off at a warehouse. For independent contractors, responsible for their own gas and operating costs, speed is tantamount to profitability. A traffic jam can turn the trip from profit to loss. So truckers often take shortcuts down small residential roads, unequipped for weight and traffic, to shave valuable minutes off their commute. Sometimes they’ll get stuck in narrow intersections. “No Trucks” signs are ubiquitous, but they’ve been of little use as deterrents.

“Truckers are different than they used to be,” Buss told me. “They’re just some guy off the street who bought some junk truck.” Later, we spotted a semi heading into a residential neighborhood, surging past “No Trucks” warnings. Buss flipped his lights on and sped to overtake the truck, swinging his pickup in front of it to bring it to a stop. “It’s gonna be a problem trying to get him out of here,” Buss grumbled. “There’s no training now. Most of these guys don’t know how to back up.”

Sure enough, the escape proved challenging. As the driver pulled forward to line up a three-point turn, the truck teetered dangerously on the edge of the road. Buss had to get out and wave the driver through the process. Ten minutes later, the truck finally made its exit. “It’s like this every day,” Buss said. “Every day.”

The only thing more common in Will County than the “No Trucks” signs are the hiring notices from temp agencies. The county is home to 99 in all—one of the highest concentrations of staffing agencies in the country. They share lofty, aspirational monikers, like Paramount, Accurate, and Elite. Amazon has its own preferred staffing agency: Integrity.

Temp agencies existed before the Intermodal came along—they played a crucial role in breaking the union stranglehold on labor in the Joliet Caterpillar plant. But the arrival of the logistics industry created a whole new market for temporary work. On the day I arrived, my hotel in Joliet was hosting a job fair for a staffing company called Geodis, which was looking for seasonal workers to help box Legos. After I inquired, they told me they’d be willing to hire me on the spot and start me on Monday, provided I could lift 50 pounds. They asked me to sign a 90-day contract, “temp-to-hire,” after which I’d be evaluated for a potential full-time role.

Antonio Suarez drove 45 minutes from the suburbs of Chicago for the opportunity to interview with Geodis. He was hired right away. “It seems too good to be true,” he joked nervously. Suarez told me he was expecting to work 30 hours a week for Geodis, which would complement the 30 hours he was working as a special needs caregiver. He also worked part time for his mom’s catering company, and was on his way to yet another gig delivering pizzas. He expected he would soon be brought on full-time by Geodis.

While “temp-to-hire” may sound promising, the latter stage of that progression can prove elusive. A full 63 percent of the warehouse workforce in Will County is temp labor or provided by staffing agencies. At a recent hearing in Joliet to deliberate the establishment of two new companies, one group claimed that only 23 of their 147 workers had been placed in permanent full-time jobs. “And that’s their own data!” said Roberto Clack, associate director of Warehouse Workers for Justice, a Chicagoland advocacy group. “I’m not sure we believe it’s even that high.”

While Will County’s reliance on temp labor force may seem extreme, it’s part of a larger national trend. A 2016 study by Harvard and Princeton researchers dug into federal employment numbers and found that “94 percent of the net employment growth in the U.S. economy from 2005 to 2015 appears to have occurred in alternative work arrangements,” which include temp workers, on-call workers, independent contractors, and freelancers.

In Will County, alternative work is gained haphazardly and with great effort. Prospective workers use shuttle buses to skip from warehouse to warehouse because the cost of maintaining a car is often prohibitively expensive for temp laborers. (Sometimes workers will bike or walk, adding yet another element of danger to the area’s beleaguered highways.) The first shuttle from Elite Staffing in Joliet leaves at 3:45 a.m. When I first stopped by Elite, there was a line of hopeful workers out front. I was offered the chance to work that night, but denied the chance to ride on the shuttle because there were 16 people for 14 seats and those were “for the less fortunate.” A few days later, on Sunday morning, it was less crowded. The shuttle headed to the “cold stores,” a series of heavily refrigerated food preparation warehouses in nearby Bolingbrook. The first stop was Greencore, the world’s largest sandwich maker, preparing sandwiches for chains like 7-Eleven (Greencore recently agreed to sell its U.S. operations to Hearthside Food Solutions). The workers customarily don’t know if there are hours for them until they arrive, but on this day all were given a shift.

Charles Lovett worked for Elite Staffing for years, across multiple different facilities, often spreading condiments on sandwich bread or boxing A-1 steak sauce. He got into warehousing at the recommendation of his family—his aunt, cousin, and brother have all worked in warehousing. “Everyone goes in at some point,” he told me.

For those who can’t afford a car, the shuttle is a lifeline. But it can also be a burden. Sometimes, Lovett mentioned, the shuttle departed before workers had confirmed a shift, leaving them stranded at the facility for hours at a time. It was only in July that temp agencies became legally required to provide return transportation from warehouses. And though recent reforms require them to pay their workers for time spent in transit, collecting that money can be challenging. These frustrations led Lovett to finally quit. Now, he works in the Dollar Tree in Joliet, making $8.90 an hour.

Brandin McDonald, a 38-year-old African American with a stocky build and a scar under his left eye, grew up in Joliet, where he got into trouble as a kid. In ninth grade, he was thrown out of Joliet Central High School for fighting. He spent time in juvenile detention as a teenager and did two stints in jail in his twenties, disqualifying him from much full-time work. In his younger years, McDonald worked construction. But with a booming warehouse industry just down the road, he decided to try his hand at it.

Between 2010 and 2014, he worked at the Wal-Mart facility in Elwood. There, he unloaded trucks and pallets, everything from light inventory, like artificial Christmas trees, to the unwieldy, like trampolines. That distinction was important, because McDonald, like many others, was paid not by the hour, but by the truckload. For 999 pieces unloaded, “you’d get $45, split between two people,” he told me. Small objects could be unloaded in an hour or two, but bulkier items could take three to five hours.

He hung on at the same warehouse, but his employer wasn’t Wal-Mart, historically one of the pioneers of subcontracting. As John Greuling, the CEO of the Will County Center for Economic Development, told me, “You’ll not find one Wal-Mart employee” anywhere in Elwood. The facility is run by Schneider, a third-party logistics firm, which subcontracts further, sometimes to four or five staffing agencies at a time. That arrangement has chilled any prospects of union organizing. “Under the law they’re legalized as five separate employers, you’d have to organize literally five separate companies at the same time,” Clack explained.

In his estimation, McDonald worked for “at least six or seven” different temp agencies during his three-plus years at Wal-Mart. Sometimes his 90-day “temp-to-hire” contracts would expire, not to be renewed, or they’d be extended repeatedly with the promise of full-time employment on the horizon. Inability to serve last-minute, mandatory overtime resulted in termination and a place on the “DNR” (Do Not Return) list. Illinois is already an “at-will” state, meaning an employee can be dismissed for any reason, without cause, at any time.

When a contract ended with one temp agency, he’d seek work from another, and get sent right back to the same warehouse, in the same role. During a stint with one particular agency, he did not receive benefits, sick days, or paid vacation for a whole year. Raises were out of the question. He drove to the warehouse every day just to find out if they had hours for him. At least he lived in Joliet: Some temp employees come from places as far as Chicago, southern Illinois, and Indiana, and can commute over an hour each direction.

With nearly 100 staffing agencies promising access to the same low-wage workforce, offering a competitive cost advantage to warehouses looking to staff up is nearly impossible. That pressure leads to corner-cutting of all sorts, which often includes wage theft, in the form of paying piece rates, skimping on hours, or having workers pay for their own drug tests, a process that was only recently outlawed. “How else are you going to cut costs?” posited Clack. “It’s this race to the bottom mentality.” McDonald ultimately filed a suit against Reliable Staffing for wage theft and won a couple thousand dollars in a settlement—but not before the agency tried to declare bankruptcy to avoid a payout. “That’s what they do,” he said, “they file bankruptcy so they don’t have to pay people.” (None of the staffing agencies contacted for this article responded to request for comment.)

Reliable eventually rebranded: It’s now called Dependable Staffing Group. McDonald now works at Wendy’s.

All Elwood’s problems—the choking traffic, the precarious work conditions, the crumbling infrastructure—have been compounded by an original sin: the decision to forego tax collection. With little money coming in, the village issued bonds to finance the town hall, the gleaming new sidewalks, and the stop signs that are observed only voluntarily. “At the end of the day, it turns out they cut a very bad deal,” Greuling told me. “They issued bonds for a water and sewer system that was too large. They built all of this capacity and now they have this huge debt. That’s the next chapter: How are they going to find a way to retire this debt?”

Elwood, down $30 million and counting, isn’t the only town in a hole. Neighboring towns wanted a piece of the fast-burgeoning industry, and cut their own tax incentive deals with warehouse developers. Nearby Bolingbrook, where Weathertech, Ulta, and Goya Beans moved in, is now $200 million in debt. Romeoville, home to Sony and one of the county’s five Amazon facilities, is $89 million in the red. “The area grew so rapidly that we lost the ability to regulate,” said Jerry Heinrich, who continues to advocate for the region’s prairie as head of the Midewin Tallgrass Prairie Alliance, a local environmental group. “There are a lot of hard feelings,” Delilah Legrett told me. Elwood “was a small village and they were taken advantage of by a big corporation.”

The numbers are extreme, but they’re far from unusual. Despite research indicating that tax incentives rarely motivate corporate relocation, such deals are being doled out at record rates, tripling since 1990. This year, the town of Mount Pleasant, Wisconsin (population 26,000), famously borrowed hundreds of millions of dollars to help bankroll a $760 million incentive package to Foxconn, from which they wouldn’t break even for some 30 years. Smaller, but no less ridiculous, deals pervade—in 2016, a town in Maryland offered Marriott $62 million to move its headquarters just five miles down the road.

By the time NorthPoint proposed creating what could amount to a third Intermodal, one that would bring a sprawling industrial park of 30-plus warehouses spanning Elwood and the neighboring village of Manhattan, the people of Will County had had more than enough of these development schemes. The developer promised a better deal, offering to make a one-time payment to Elwood to wipe out its towering debt. (It also claimed that this facility would bring the prosperity that the previous development had failed to deliver.) But closer examination of the paperwork showed that the company would’ve made that money back over time via the generous tax structure it was hoping to secure.

Even those promises did not assuage concerns. There were suspicions that the new facility would be hooked up to a rail line, resulting in the creation of a 270-degree perimeter of development around the town. “We would be totally boxed in,” said Julie Baum-Coldwater, who began to worry that, at that point, her family farm could be targeted for eminent domain.

Frustrated residents began to organize in opposition. Legrett and a group of fellow objectors, none of whom had experience in political activism, founded the group Just Say No to NorthPoint. They started small, ten people in a town hall in Jackson Township. But they quickly made their presence felt. Members showed up in the dozens at village board meetings. They printed yard signs, circulated petitions and group emails. Their Facebook group swelled to a thousand members, building an explicitly nonpartisan coalition that included both avowed progressives and MAGA-hat wearers. (Elwood overwhelmingly voted for Donald Trump in the 2016 election.)

After the planning and zoning board recommended the project to the Village of Elwood board for final approval, Just Say No to NorthPoint upped its activity. They teamed up with environmental groups like the Sierra Club and the Joliet branch of the worker advocacy group Warehouse Workers for Justice. They orchestrated demonstrations. “It was really impressive the way they built it,” said Roberto Clack, whose organization got involved with the campaign in the last 12 months.

The group put pressure on local politicians. Elwood Village President Todd Matichak, who was careful not to take too firm a position on the development, resigned days ahead of the planning and zoning meeting in December 2017, after just eight months on the job. “I guess the seat just got too hot for him,” said Jackie Traynere, a Will County Board Member from nearby Bolingbrook. The group also won the resignations of numerous pro-development Elwood board members. Finally, in April 2018, it was announced by interim President Doug Jenco that the project did not have enough votes to go through. The fallout was significant: Multiple board members left their posts, with one, who had proclaimed the NorthPoint development “a gift from God,” selling his house and leaving the area altogether.

It was a major victory. “What happened was the community organized, they resisted and they won,” Clack told me. “But there’s a round two.” Once news broke of Elwood’s refusal, the developer submitted an application with the Will County board, hoping to override local authority. Hearings will begin again sometime in 2019.

As summer turned to fall, Just Say No to NorthPoint trained their efforts on the Will County board. They organized a climate march in September, where environmental activists from as far Chicago marched alongside Elwood’s farmers to the BNSF facility, interrupting traffic in the process. The Coldwaters, who participated in the march, even sent a letter to Warren Buffett. “[T]he legacy you seek to leave behind by your generosity will, in reality, be tarnished by the personal hurt and damage done to others in the name of ‘business,’” they wrote. So far, Buffett hasn’t responded. (BNSF also declined to comment for this article.)

In early November, the city of Joliet rejected the applications for the two new staffing agencies it was considering, another small victory that would’ve seemed unthinkable a year ago. Nearby towns have begun negotiating better deals with warehouse developers. “A lot of people saw the campaign and then became empowered by it,” said Stephanie Irvine, one of the founders of Just Say No to NorthPoint.

But when it comes to the long-term prospects for the region, optimism is scarce. Paul Buss’s son, who works as a building inspector in Joliet, told his dad there’s concern “these companies are gonna come in, they’re gonna build these buildings, and they’re gonna use them for however long they can get a tax break on them, and then they’ll move someplace else.” The threat of empty warehouses looms large.

So, too, does the threat of automation. In 2017, it was estimated that 20 percent of the work in any given Amazon warehouse is automated, a figure that is expected to rise. This fall, IKEA opened up a new warehouse, 1.5 million square feet in total. “Fully automated,” John Greuling told me, it will have about 200 employees. Incredulous, I counted all the spots in the parking lot: 226.

Brandin McDonald told me he was concerned that they’d be left with a bunch of warehouses empty of people, terrible jobs having given way to no jobs at all. Legrett said she was worried about it, too. “What are all these buildings going to look like in 10 years?” she asked.