For an artist who specialized in the uncanny, Edward Gorey has become a little too familiar. Perhaps this is the inevitable fate of writers and artists distinctive enough to have an adjective named after them. The word “Goreyesque” immediately conjures a handful of images and tropes: crepuscular mansions, statuary urns, unquiet spirits, desolate moors, and small children meeting untimely ends. He drew this iconography from fin de siècle gothic horror, but the gothic, in Gorey’s work, is never played straight. It’s always mixed, in his biographer Mark Dery’s words, with “a shot of black comedy, a jigger of irony, and a dash of high camp.”

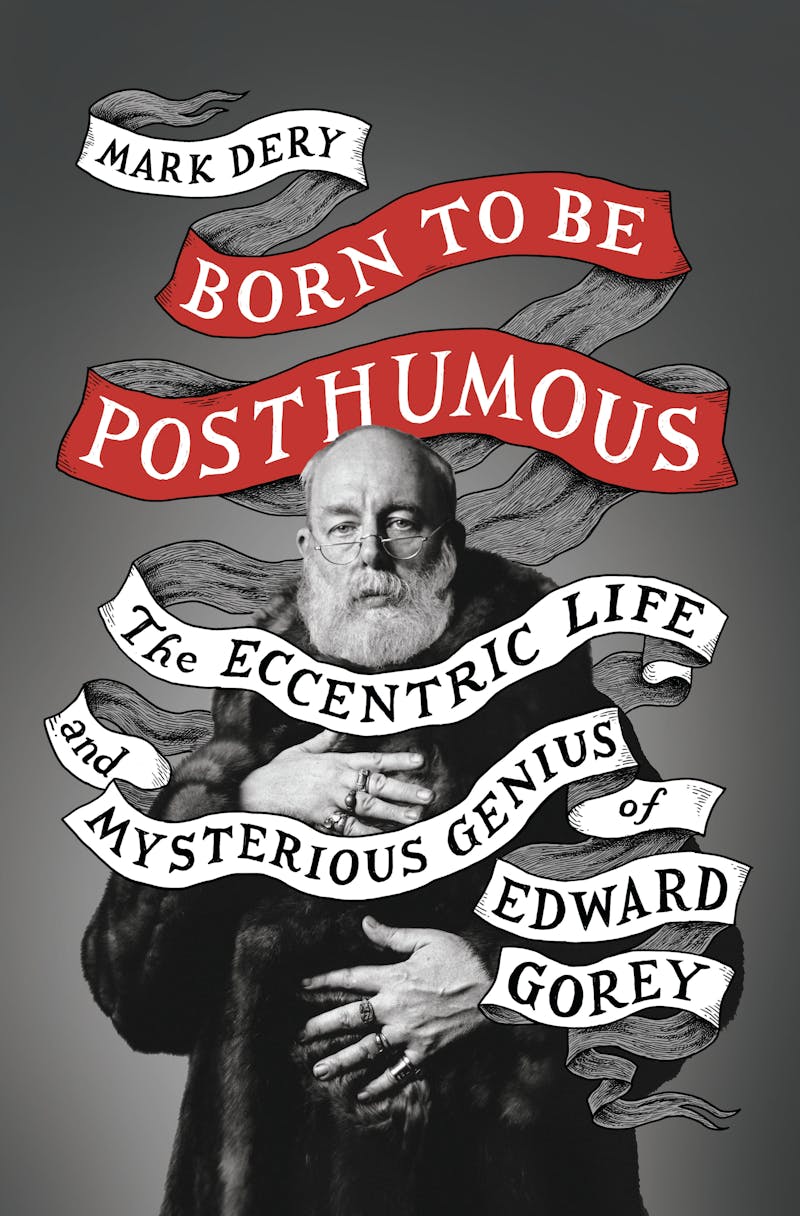

Gorey is widely acknowledged as the master, if not the in- ventor, of this mode. Even people who haven’t read The Doubtful Guest or The Gashlycrumb Tinies will likely recognize Gorey’s elegant, fastidiously crosshatched pen-and-ink drawings of waifish orphans and bald-headed, bearded men in long fur coats and tennis shoes. As Dery points out in Born to Be Posthumous—the first full-length biography of Gorey to appear since his death in 2000—he has exerted a durable influence on popular culture, as Young Adult novelists like Lemony Snicket, Neil Gaiman, and Ransom Riggs have brought his arch aesthetic to a large and fervent audience. His own works, meanwhile—once available only in limited-edition volumes—now adorn coffee mugs, calendars, refrigerator magnets, iPhone cases, and even salad tongs.

One drawback of this popularization is that Gorey is too easily pegged as the peddler of a kind of twee-goth miniaturism: “Dr. Seuss for Tim Burton fans,” as Dery puts it. Even during his lifetime, he resisted being described as “macabre.” “It sort of annoys me to be stuck with that,” Gorey told a journalist in the late 1970s. “What I’m really doing is something else entirely.” The gothic, for Gorey, was one costume among many, and while it’s clearly one in which he felt especially comfortable, his work radiates a melancholy and an existential unease—as well as a formal inventiveness—that none of his imitators have matched, and that small samplings of his work don’t reveal.

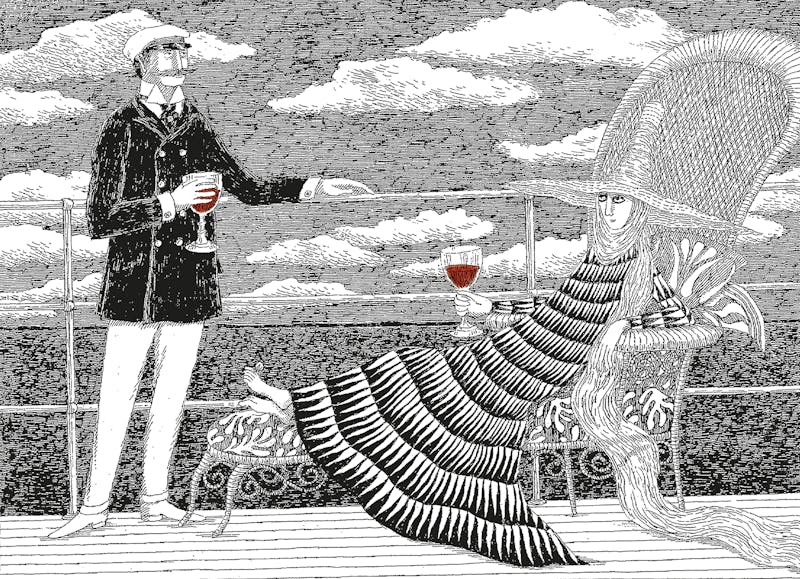

It’s very hard, in fact, to put one’s finger on the Goreyesque—at least as Gorey himself practiced it. His aesthetic, Dery writes, is “an aesthetic of the inscrutable, the ambiguous, the evasive, the oblique, the insinuated, the understated, the unspoken.” It’s easy to forget how little happens in much of Gorey’s work, how essentially atmospheric it is, in both its horror and its humor. A creature of habit (with a habit of inventing creatures), Gorey was at least as attracted to the quotidian as he was to the bizarre. “Life is intrinsically, well, boring and dangerous at the same time,” he told the writer Alexander Theroux late in his life. “At any given moment the floor may open up. Of course, it almost never does; that’s what makes it so boring.”

Although he played up his eccentricities in public, Gorey was fundamentally a shy, private man who seemed to take a perverse pride in the dullness of his own existence. “My life is as near not being one as is possible I think,” he wrote to a friend in 1951, and things didn’t pick up much from there. He had relatively few friends, and virtually no close ones. He lived alone (or, rather, with cats) for decades, first in Manhattan and later in a Federal-style house on Cape Cod. He had no sexual or romantic relationships that we know of, and his rise to relative fame in the 1970s and ’80s changed his lifestyle very little.

Born in Chicago in 1925, the only child of middle-class parents, Gorey taught himself to read at three and a half, and was soon consuming Victorian and Edwardian classics in copious doses, including Dickens and Dracula, as well as the then-new detective novels of Agatha Christie. (All of these left a permanent impress on his imagination: Though Gorey never visited England, he was a lifelong Anglophile; many of his more casual fans still assume he was British.) In 1942, he won a scholarship to Harvard, but the draft delayed his matriculation. He spent the duration of World War II doing clerical work at an Army base in Utah, and amused himself by writing closet dramas under the pseudonym “Stephen Crest.” In these plays, Dery reports, “the characters have names like Piglet Rossetti and Basil Prawn and dress more or less the way you’d imagine people named Piglet Rossetti and Basil Prawn would dress—in purple espadrilles and ‘mauve satin ribbons [that] cling like bedraggled birds to bosom, thigh, and wrist.’” His fellow recruits were, presumably, baffled.

Gorey’s aesthetic idiosyncrasies blossomed when he finally arrived at Harvard in 1946. It was during this period that he adopted the extravagant costume he would later be famous for: Dery describes him “swanning around campus in his signature getup of sneakers and a long canvas coat with a sheepskin collar, fingers heavy with rings.” (Later on Gorey would favor raccoon coats, but he never ditched the tennis shoes.) He also grew a full beard that made him resemble the solemn Edwardian patriarchs who would soon populate his books. He roomed with the poet Frank O’Hara (they shared a fondness for Marlene Dietrich, and had a tombstone for a coffee table) and befriended other future literary luminaries like John Ashbery, Donald Hall, Barbara Epstein, and Alison Lurie.

After college, Gorey moved to New York to take a job at a new paperback imprint called Anchor Books. There he designed book covers for reprints of classic novels by Herman Melville, Henry James, and others, and crucial elements of his style evolved, including his distinctive hand-lettering, which arose from his frustration working with type. It was also around this time that he developed a quasi-religious devotion to the choreographer George Balanchine, the artistic director of the New York City Ballet, where Gorey maintained an almost perfect attendance record between 1956 and 1979; he would later call Balanchine “the great, important figure in my life … sort of like God.” (Dery observes that “Gorey’s characters often strike balletic poses and tend to stand with their feet turned out, in ballet positions,” as Gorey often did himself.)

Gorey’s reputation built gradually. From the start his works were prominently displayed at the counter in the Gotham Book Mart, a legendary independent bookstore in midtown Manhattan, which brought him to the attention of literary tastemakers. His first book, The Unstrung Harp, was published in 1953. It told the story of Mr. Clavius Frederick Earbrass, an author afflicted by writer’s block; Graham Greene called it “the best novel ever written about a novelist.” His small cult following expanded considerably when Edmund Wilson devoted a column to “the albums of edward gorey” in the pages of The New Yorker in 1959. In 1972, Amphigorey, a mass-market omnibus reprinting 15 of Gorey’s little books, became a surprise best-seller. Other milestones were the 1977 Broadway production of Dracula, starring Frank Langella, for which Gorey designed the sets and costumes, and the 1980 premiere of the PBS television series Mystery!, featuring an animated credit sequence based on images from Gorey’s books.

By the time he died in 2000, Gorey was a minor celebrity, much sought after both as a freelance illustrator and as a profile subject. He devoted his last years on Cape Cod, touchingly, to writing, designing, and directing avant-garde plays for a local theater troupe called Le Théatricule Stoïque. One of them, Omlet, or Poopies Dallying, was a collage of garbled texts from early versions of Hamlet, performed with handmade papier-mâché puppets. From Dery’s descriptions, these shows, few of which ever made it off the Cape, were as strange as anything in the Gorey oeuvre, and proof of the strong streak of perversity that never deserted him.

One of the virtues of Dery’s book is its reminder that Gorey’s art was far more subtle, diverse, formally inventive, and just plain weird than his reputation for sinister whimsy suggests. In the 100-odd books that he published during his lifetime—books with three-word titles like The Fatal Lozenge, The Pious Infant, The Blue Aspic, The Disrespectful Summons—he experimented promiscuously with format. He crafted abecedaries (alphabet books), postcard sets, pop-up books, “slice books” (in which the reader can mix and match portions of an image to create new ones), and even a variant of the choose-your-own-adventure story (from 1987’s utterly confounding The Raging Tide: “Hooglyboo crammed Figbash inside a vase. If this strikes you as clever, turn to 11. If all this seems too terrible to contemplate, turn to 29.”)

He was also, more than we tend to think, an artist of his time. While the popular conception of Gorey is of a man born 50 years too late, a stubborn antiquarian who was always, in Dery’s words, “signaling a conscientious objection to the present,” he saw himself as working in the tradition of the twentieth-century avant-garde. “If I had to say I’m like anyone I suppose it’d be Gertrude Stein and Beckett,” he told a reporter in 1992, and he also took inspiration from contemporaries like Jorge Luis Borges and Raymond Queneau. (Gorey, in turn, inspired other avant-gardists: See the Austrian jazz composer Michael Mantler’s 1976 album The Hapless Child, for example.)

Gorey’s avant-garde bona fides are visible in his work’s combination of absurdity with rigorous formalism: The books tend to take essentially arbitrary conceits (a parody of Victorian pornography, a series of very slightly asymmetrical landscapes) and stretch them as far as they can go. The obviously labor-intensive character of Gorey’s immaculately crosshatched drawings, which often resemble Victorian engravings, adds to the sense of provocation. One is constantly moved to think: He put all that work into this?

Surrealism, particularly the collage novels of Max Ernst, strongly influenced Gorey. Some of his books assume the trappings of conventional narrative genres like the detective story or the morality play, but many are really exercises in dream logic. The Object-Lesson, for instance, begins, “It was already Thursday, but his lordship’s artificial limb could not be found,” and proceeds from there through a series of eerie non sequiturs, crescendoing with the immortal lines: “On the shore, a bat, or possibly an umbrella, disengaged itself from the shrubbery, causing those nearby to recollect the miseries of childhood.”

Other books take a Steinian delight in the play of language: the text of The Nursery Frieze, for instance, is a string of recondite single words (“accismus,” “badigeon,” “epistle,” “quodlibet,” “hiccup”) spoken by a stubbornly advancing capybara. In L’Heure Bleue, two dogs wearing burglar masks and matching letterman sweaters engage in a Beckettian dialogue: “It is not the living, it is the being lived on,” one dog sagely observes. “I must remember to write that, along with some other things, down,” the other replies. And a book as bonkers as The Inanimate Tragedy (“‘Death and Distraction!’ said the Pins and Needles. ‘Destruction and Debauchery!’ Almost at once the No. 37 Penpoint returned to the Featureless Expanse.”) is closer in spirit to Marcel Duchamp or Lautréamont than it is to Tim Burton or Lemony Snicket.

Works like these are the best evidence for Gorey’s claim that he’s “doing something else entirely,” or trying to: You can feel him pushing the limits of his chosen medium—the illustrated book—just as Stein and Queneau pushed the novel, Beckett the play, or Duchamp the painting. If Gorey’s work lacks the philosophical heft of his modernist predecessors, he makes up for it with sheer experimental brio, not to mention beauty. He is at once essentially limited and infinitely ambitious.

At over 500 pages, Born to Be Posthumous is a baggier, less discerning biography than Gorey deserves. (He was nothing if not economical in his own work: “I like … leaving things out, being very brief,” he once said.) And yet, despite its length, it often feels factually thin. Although Dery’s research into Gorey’s life brings to light some fascinating details, there are so many lacunae that he frequently resorts to speculation. The book’s pages are littered with qualifications such as “Who knows,” “It’s easy to imagine,” “We don’t know,” “We can only guess,” “We have no idea,” and “Who can say?”

One of the many things Dery can only guess about is Gorey’s sexuality, which features heavily in his introduction, his conclusion, and in several passages throughout. Dery notes that Gorey’s friends were predominantly gay men, and that nearly everyone who met him believed him to be gay, but that he often equivocated about his sexual identity in interviews. He told a journalist who asked him about his sexual preference in 1980 that he was “neither one thing nor the other particularly.” In the original published article, he adds, “I suppose I’m gay. But I don’t really identify with it much.” As a lifelong celibate, he pointed out, he was basically asexual: “I’ve never said that I was gay and I’ve never said that I wasn’t. A lot of people would say I wasn’t because I never do anything about it.” Indeed, though his letters attest to a series of obsessive crushes (all on men), there is no evidence that Gorey ever had sex with anyone, male or female.

It’s perfectly legitimate, of course, for biographers to pay attention to their subjects’ sex lives—or, in Gorey’s case, their lack thereof. But Dery insists on treating what seems like a fairly cut-and-dried situation as a “mystery.” “Of all the contradictions [Gorey] contained, his sexuality was surely the most puzzling,” he writes toward the end of Born to Be Posthumous. “The question of Gorey’s sexuality has all the makings of a good mystery.” But is there really anything very puzzling or mysterious about a man who came of age in the 1950s, and whose life was largely celibate, being reluctant to publicly identify himself as gay? Under the circumstances, Gorey’s answers to this line of questioning seem to have been pretty candid.

Dery is right to point out that “media coverage of Gorey is consistently … oblivious to the gay themes in his art, the gay influences on his aesthetic, the gay origins of his persona.” The Gorey estate has even collaborated, to an extent, in this erasure: In the collection of interviews Ascending Peculiarity: Edward Gorey on Edward Gorey, the addendum to Gorey’s answer about his sexuality (“I suppose I’m gay. But I don’t really identify with it much.”) has quietly disappeared; the text now reads simply, “Well, I’m neither one thing nor the other particularly.” (Dery attributes the deletion to Andreas Brown, one of Gorey’s literary executors.) It’s also undeniable that many of the writers and artists Gorey most admired—Ronald Firbank, Ivy Compton-Burnett, E.F. Benson, Edward Lear, Saki, Stein—were gay. If he was not quite homosexual, in other words, he was certainly queer. (That the word has Victorian overtones only makes it more perfect.)

Yet Dery struggles to produce queer readings of Gorey’s work that significantly enrich our understanding of it. When he tries, the results are clumsy, alternately unconvincing and obvious. He notes that “the image of a man with a well-rounded rear seen from behind is something of a motif in Gorey’s work” and that books like The Gashlycrumb Tinies and The Beastly Baby imply an ambivalent attitude toward children and reproduction—we’re not exactly talking Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick here. After reading Dery, I’m fully convinced that there’s a great book to be written about Edward Gorey as a queer artist. Born to Be Posthumous, unfortunately,

is not it.

There is something quixotic, in the end, about trying to define Edward Gorey according to any one social or historical context—although that, of course, is what biographers do. Gorey loved antiques, and he wanted his books to look like something from another age; at the same time, he wanted to be absolutely modern. His body of work is both utterly consistent and continually surprising, immediately recognizable and aesthetically restless. It makes a mockery of the gothic, placing horrific imagery in quotation marks, but still manages to be genuinely unsettling: Gorey’s parodies of nineteenth-century nightmares remain disturbing in the twenty-first.

It’s hard to imagine that Gorey would approve of the “Goreyesque” as it has been codified since his death. It’s clear that he disliked the very idea of even having a style, let alone lending his name to one. “I hate being characterized,” he once told a reporter. “I don’t like to read about ‘the Gorey details’ and that kind of thing.” Many of his books were not even published under his own name: He frequently preferred pseudonyms, usually anagrams of “Edward Gorey” (Ogdred Weary, Wardore Edgy, Dogear Wryde, Regera Dowdy, Garrod Weedy).

But style is a funny thing: It stands both for something willed, an intended effect, and something inevitable and inescapable that artists are helpless to disguise. The greatest stylists—and Gorey was one of them—struggle with their natural impulses, challenging themselves to avoid falling back on easy habits and recognizable tics. Yet their idiosyncrasies never really disappear. Gorey may be stuck, in the public imagination anyway, with the “Goreyesque”—a familiar, even comforting repertoire of images that fit right in on a refrigerator magnet. But we can always find, on closer look, those moments when the floor opens up, and everything seems strange again.