To stop kids from smoking, Food and Drug Administration Commissioner Scott Gottlieb wants to stop nicotine from tasting like candy. So he proposed two new restrictions on cigarette and e-cigarette products on Thursday.

One proposal, which has dominated the media coverage, would make flavored e-cigarettes—also known as vape pens, or vapes—much harder to access. Gas stations and convenience stores would only be allowed to sell tobacco- or menthol-flavored vapes, since those are often used by cigarette smokers who are trying to quit. Vape flavors like cotton candy and raspberry would be relegated to “age-restricted, in-person locations” such as liquor stores and specialty tobacco shops. Online sales would be more closely monitored.

The announcement is already having an impact: Juul, the market leader in e-cigarettes, announced that it will stop selling most of its flavored products in stores.

Gottlieb’s other proposal has drawn less attention, but is more controversial: an outright ban on menthol cigarettes. “I believe these menthol-flavored products represent one of the most common and pernicious routes by which kids initiate on combustible cigarettes,” he said in his statement.

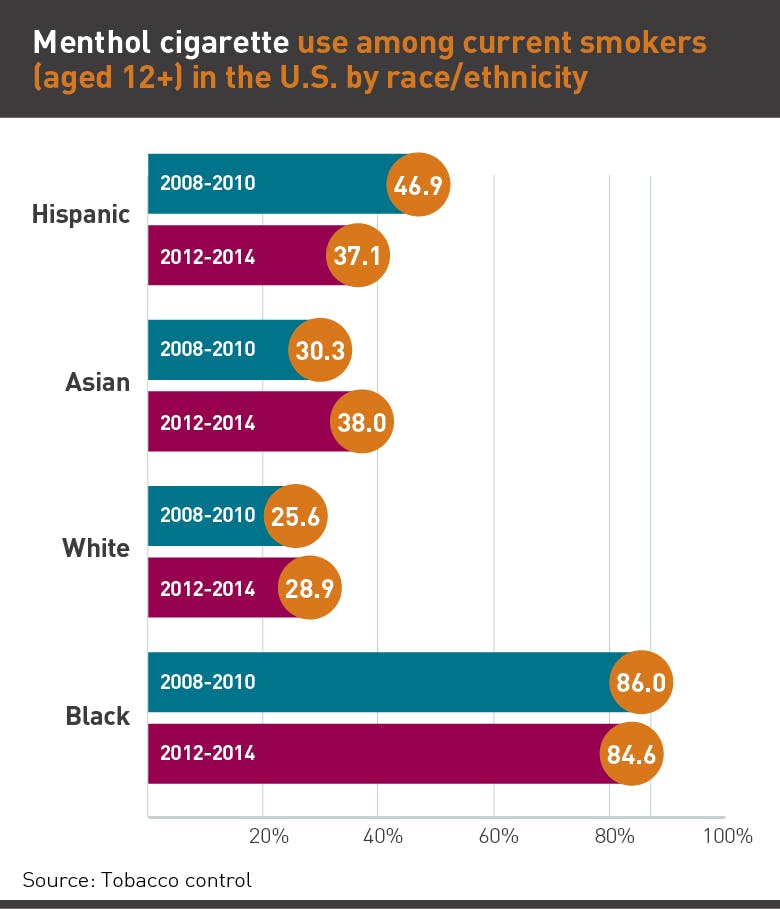

Young people have been shown to be more likely to try a menthol cigarette over a regular one, since the minty flavor masks tobacco’s harsh taste. But young Americans aren’t the predominant smokers of menthol cigarettes. Black Americans are. According to Truth Initiative, a non-profit tobacco control group, nearly 85 percent of black smokers prefer menthol cigarettes, compared with only about 29 percent of white smokers. So Gottleib’s announcement caused some on Twitter to wonder: Is the proposed ban racist?

The question is not a new one. It came up frequently in 2010, when the FDA was considering a similar ban. Though it eventually failed, that proposal “caused a rift among forces that advocate on behalf of blacks’ interests,” NPR contributor Deron Snyder wrote at the time. Groups like the NAACP and the African Tobacco Control Leadership council were supportive, saying it would reduce rampant health problems in the black community. Groups like the National Black Chamber of Commerce, however, saw the ban as a racially targeted infringement on black smokers’ freedom of choice. “Menthol simply is a taste preference preferred by African Americans and it should not be singled out for a ban,” the group’s co-founder Harry Alford said in 2011.

Snyder agreed. “Why would the government ban the cigarettes that I prefer, while the estimated 78 percent of non-Latino, white smokers who prefer non-mentholated cigarettes are allowed to keep on puffing?” he wrote, adding that a cigarette ban should not be applied unless all cigarettes were banned. Reason magazine made a similar argument in 2017, as several cities passed ordinances banning the sale of menthol products. “It is true that black smokers use menthol cigarettes at a greater rate than the average American smoker,” Christian Britschgi wrote. “But does that mean the proper anti-racist response is to crack down on menthol? Indeed, is it not perhaps a tiny bit discriminatory to prohibit a product primarily because of the race of the people buying it?”

Proponents, however, argued that banning menthol cigarettes is actually an anti-racist policy—a way to combat the tobacco industry’s racist marketing strategies. “Cigarette companies know that most African-American smokers prefer menthol cigarettes and they exploit this preference in their marketing efforts to African Americans, in general, and to African-American kids, in particular,” the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids wrote in a memo that compiled research on the subject.

It’s true: Menthol cigarettes are disproportionately advertised in predominately black communities, and the ads in those communities are disproportionately directed at young people. A 2010 study by the Harvard School of Public Health comparing tobacco marketing in two racially disparate neighborhoods found that the predominantly black one “had more tobacco retailers, and advertisements were more likely to be larger, promote menthol products, have a lower mean advertised price, and occur within 1000 feet of a school” than the predominantly white one.

That strategy has had profound consequences for the health of black communities. Smoking-related illness is the largest cause of preventable death among African Americans—more than homicides or even car accidents. According to the CDC, “Although African Americans usually smoke fewer cigarettes and start smoking cigarettes at an older age, they are more likely to die from smoking-related diseases than Whites.” It’s not clear why that is, but the CDC notes that black smokers are less successful at quitting cigarettes than other ethnic groups. Menthol cigarettes also have been shown to be harder to quit than regular ones.

Further complicating the debate, tobacco companies have given millions of dollars to black organizations and politicians. The National African American Tobacco Prevention Network referred to it in 2015 as the industry’s “informal mutual aid pact with some black organizations,” including the NAACP and the United Negro College Fund. In return for donations, “some of the groups have helped the industry fight anti-smoking measures. Other times, critics say, they have simply turned a blind eye to the harmful impact of tobacco on the black community.” A Mother Jones investigation from 2015 found that “half of all black members of Congress received financial support from [tobacco company] Lorillard, as opposed to just one in 38 nonblack Democrats. To put it another way, black lawmakers—all but one of whom are Democrats—were 19 times as likely as nonblack Democrats to get a donation.”

With a menthol ban in the offing again, these relationships are sure to see renewed scrutiny. But Gottlieb has made clear where he stands. “I believe that menthol products disproportionately and adversely affect underserved communities,” he said in his Thursday statement. “And as a matter of public health, they exacerbate troubling disparities in health related to race and socioeconomic status that are a major concern of mine.”