Linguists have figured out a lot about the many different regional dialects of American English. They know why Brooklynites say “cawfee,” for example, and why Bostonians say “Hahvahd Yahd.” They’ve traced the history of our accents and phrases: how migration patterns influenced their development, and how technology shaped their recent evolution. But what do they know about how Americans will talk in the future?

Not a lot. Outliers in the field believe that the dialects of American English will die—or at least slowly fade—as technology expands connections between people from different regions. But everyone agrees that Americans won’t always speak like we do today. And one of the best ways to predict those future changes is to study places where American speech is shifting right now.

One of the most interesting such transformations is happening in New Orleans, according to Katie Carmichael. The linguistics researcher and assistant professor at Virginia Tech has been researching the Southern Louisiana city’s unique drawl for years. “It changes every six months, who lives there and what they’re arguing about,” she said. “Every time I go back there, it’s such a different place.”

In years of conversations with New Orleans residents, however, Carmichael has noticed one thing that’s always the same. “There’s not a single person who doesn’t bring up Hurricane Katrina,” she said. That observation led Carmichael to develop a unique hypothesis: Maybe the hurricane that devastated New Orleans in 2005 did more than just change the city’s physical and cultural landscape. Perhaps it altered how New Orleanians speak, too.

New Orleans English can be confusing to those who aren’t familiar with it. “Some of them speak with a familiar, Southern drawl; others sound almost like they’re from Brooklyn,” Jesse Sheidlower, the former editor-at-large of the Oxford English Dictionary, wrote in a definitive explainer of the dialect in 2005, shortly after Katrina. “Why do people in New Orleans talk that way?”

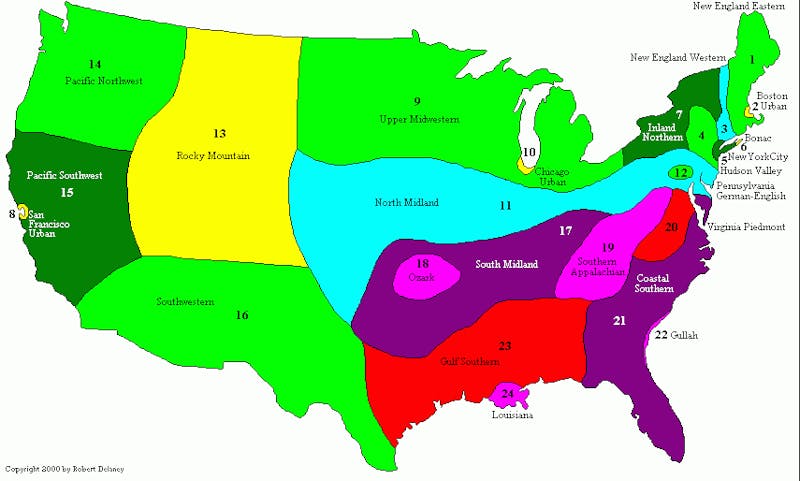

The “rich level of linguistic diversity” in New Orleans stems, in part, from its diverse migrants, he wrote. There were the French and Acadian settlers, of course, as well as Spanish, German, Irish and Italian immigrants. New Orleans was also “a gateway for the slave states, which brought in speakers of a variety of African languages.” The result was the hodgepodge of subdialects that exist there today, which change depending on the neighborhood or ethnic group.

Carmichael can’t yet say specifically how New Orleans English has changed since Katrina. But last week, the National Science Foundation awarded a $250,000 grant to Carmichael to explore her hypothesis, along with Tulane University linguistics professor Nathalie Dajko. Together, they “will interview 200 lifelong residents of different ethnic backgrounds and neighborhood origins to collect the largest and most diverse data sample ever assembled in the city,” according to a press release. The results could help researchers predict other dialect changes that might occur as sea-level rise and more severe storms force Americans away from the places that once shaped their speech.

Carmichael’s hypothesis is based on two known impacts of Katrina that are also known to spur dialect changes: Widespread displacement of native speakers from the region and widespread migration of non-native speakers into it.

Katrina’s flooding displaced 400,000 people—nearly the entire population of the city. A year later, only about 53 percent of those people had returned—“less than a third at the home they’d lived in prior to Katrina,” according to CityLab. Today, the city has around 80 percent of the population it once had, but it’s been difficult to track with precision how many are newcomers and how many are longtime residents. But one thing is for sure: New Orleans is a smaller, whiter city than it used to be. There is thus concern that some New Orleans subdialects could be at risk of disappearing. After all, Carmichael said, “Some of our major cities in the South no longer sound Southern because economic prosperity brought Northerners in.”

A severe example of climate change–fueled displacement is happening not far from New Orleans at Isle De Jean Charles, a Louisiana island that’s slowly sinking into the ocean. The community there is one of the last vestiges of Louisiana Regional French, and some scholars worry that an exodus of residents—who are often called America’s first climate refugees—will eradicate that dialect. “Sometimes when people move away, they leave the language behind,” said Dajko, who is writing a book about linguistic changes on the island.

There is hope, though, for both New Orleans English and Louisiana Regional French, and it rests in part on the strong sense of identity that comes with a unique way of talking. If people feel their identity is threatened—that their dialect is fading—they may work harder to preserve it. Carmichael hypothesizes that as a result of Katrina, some ethnic populations in New Orleans may retain their unique older dialects for longer than they would have otherwise.

While she and Dajko work to figure that out, though, they hope the mere idea of their research will provoke others to think about how climate change might affect American English in the future. “These mass migration scenarios are more likely to happen again,” Carmichael said. That’s not only because of hurricanes, which are getting more intense, but also due to sea-level rise.

If warming continues unabated, up to 13.1 million Americans living in coastal areas could be permanently displaced. More than one million people are at risk in Louisiana, further threatening the regional dialect. But so are 900,000 in New York, 800,000 in New Jersey, and 400,000 in Texas. “Climate change is going to be a catalyst for a mass migration that will result in language change,” Dajko said. What that heralds for y’all and yous guys remains to be seen.