At a small jail outside San Salvador, Brother David Borja lifted his sunglasses to talk a guard into letting us inside. The cell, originally intended for temporary holding, smelled of sweat and urine. In the center was a roughly ten-by-ten-foot cage, and inside it, a tangle of limbs and hammocks.

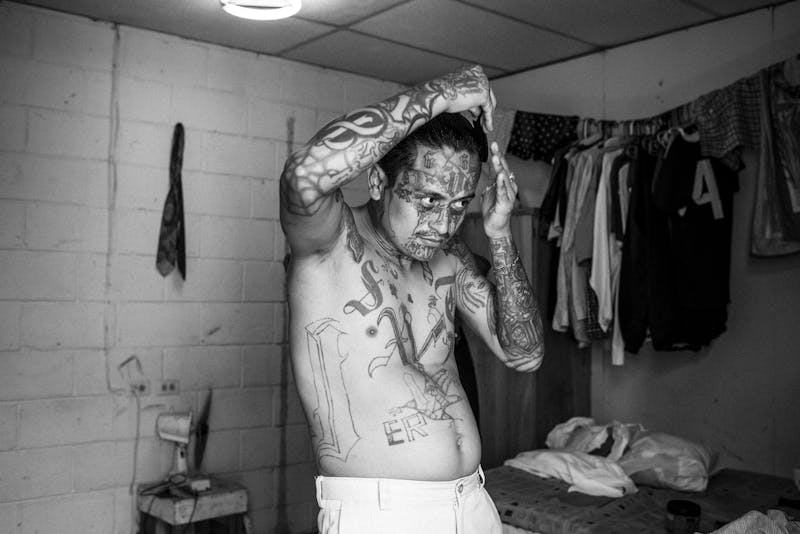

At the sight of Borja, a street preacher from the Baptist Biblical Tabernacle “Friends of Israel” church, bare-chested, tattooed young men began crawling down from the hammocks and pulling on T-shirts.

As Borja started to pray, the men crossed themselves and bowed their heads. A few cried silently; others testified, “Truth.” One stuck his hand out of the bars. He held a bracelet, woven in a flower pattern from colorful plastic bags. Soon, a dozen held out bracelets. Borja collected them without pausing.

Borja closed his Bible and banged on the door, explaining that the bracelets were gifts for street children. As the guard latched the thick steel behind us, we could still hear the men’s applause, and pleas for the pastor to pray for them to be saved.

Founded in 1977, the Baptist Biblical Tabernacle “Friends of Israel” church, known as “Taber,” is now believed to be El Salvador’s largest church. Taber claims a congregation of more than 40,000, with millions of converts and more than 500 churches across the country. The megachurch also owns a handful of TV and radio stations and newspapers, extending its reach. In 1950, El Salvador was around 99 percent Catholic, but Protestantism has shot up since the 1970s, with 40 percent of adults today identifying as Protestant.

That makes Taber one of the most influential institutions in a country otherwise dominated by gangs.

El Salvador’s gang problem is American-made. From 1980 to 1992, Washington poured billions into the country, roughly the size of Massachusetts, backing right-wing military oligarchs battling leftist revolutionaries. The conflict killed 75,000 people, and tens of thousands more fled north. In Los Angeles, Salvadoran immigrants and refugees formed a street gang called MS-13, and began joining rival Barrio 18, a Mexican gang. President Bill Clinton signed a law fast-tracking deportations, and between 2001 and 2010, the United States deported more than 40,000 convicts back to El Salvador, exporting the gangs. Amid the war-tarnished ultra-conservative Catholic clergy and military, and the decentralized, barrio-based Evangelical churches, the gangs thrived.

Today, MS-13 is Central America’s largest gang, having built a transnational brand on brutal violence; one motto is “rape, control, kill.” MS-13 also provides U.S. President Donald Trump with a convenient bogeyman to justify a broader immigration crackdown in the name of protecting the homeland. “When we have an ‘infestation’ of MS-13 GANGS in certain parts of our country, who do we send to get them out? ICE!” Trump tweeted in July, referring to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement—and the upcoming November midterms: “They are tougher and smarter than these rough criminal elelments [sic] that bad immigration laws allow into our country. Dems do not appreciate the great job they do! Nov.”

On October 15, Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced that MS-13 poses a more serious threat to the United States than any designated transnational crime group—even Mexican cartels and terrorist organizations. In reality, while El Salvador’s defense minister has claimed that some 500,000 Salvadorans are involved in gang activity at home, with roughly 60,000 active gang members in a total population of 6.5 million, U.S. authorities have estimated for more than a decade that MS-13’s American membership has remained at about 10,000 members, less than 1 percent of approximately 1.4 million gang members nationwide. There’s little indication that Salvadorans fleeing gang violence have increased MS-13’s numbers north of the border. Still, Trump’s apocalyptic rhetoric has given Salvadoran street gangs’ vicious reputation a global boost.

According to experts, one of the gangs’ golden rules is that members can never leave with their lives. But in the past few years, there’s been a fascinating development: Gang bosses are increasingly granting those under their command desistance—a status change from “active” to “calmado,” meaning “calmed down”—if they convert to evangelicalism. At El Salvador’s San Francisco Gotera prison, about 1,000 ex-gang members have become evangelicals, nearly all of the overcrowded prison’s occupants.

The phenomenon can also be seen outside, at smaller Pentecostal parishes such as Ebenezer, whose ministry to gang members, The Final Trumpet, is known for speaking in tongues. Newfound-religious who stray from the righteous path, however—whether by drinking, doing drugs, beating their wives or girlfriends, or not attending church—can face deadly consequences from their former compatriots.

It’s an open, urgent question whether evangelical megachurches like Taber can use their influence to bring peace to El Salvador—or whether this is just one more union of political convenience that’s doomed to combust.

“This is a powerful book,” said Edgar López Bertrand Jr., raising a Bible at Taber’s massive headquarters in San Salvador.

López Bertrand, his office full of floor-to-ceiling bookshelves and Harley-Davidson paraphernalia, has formally headed the megachurch since late 2017, when his father, Edgar López Bertrand Sr., died. Just after his takeover, El Salvador’s police chief announced that homicides had dropped 25 percent from 2016. Both the gangs and government take credit for the continued decrease in the national homicide rate, but it’s also vindicating for pastors like López Bertrand, better known as Toby Jr., who have put their credibility on the line by supporting gang rehabilitation.

“Churches have huge opportunity and power to change the national narrative from ‘kill them all’ to ‘we need a peace process,’” said Noah Bullock, executive director of Cristosal, an El Salvador-based human-rights nonprofit. “But there’s a lot of political risk.”

The stakes for gang outreach are rising ahead of El Salvador’s 2019 presidential election, as the gangs face a renewed offensive from the combined forces of San Salvador’s security state and President Trump, who has prioritized the war on gangs at the expense of other aid. Both the left-leaning Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front, FMLN, and the opposition party, the conservative Nationalist Republican Alliance, ARENA, have again endorsed gang crackdown as their security strategy, a policy largely indistinguishable and unchanged through two decades of elections.

In 2003, the ARENA government launched mano dura, an “iron-fist” approach imitating the American anti-gang strategy. After FMLN won the presidency for the first time in 2009, even the party’s guerillas-turned-politicians continued the militarized response. In overcrowded prisons, the gangs established control and consolidated power. Homicides continued to rise.

“The challenge for the two main parties is which can present itself as the tougher on crime,” says Jose Miguel Cruz, director of research at Florida International University’s Latin American and Caribbean Center. “That is their race to the bottom.”

Yet as the February presidential election looms, both FMLN and ARENA have largely evaded the gang issue, perhaps responding to voters’ apparent disillusionment with corruption and payoffs to the very criminal groups they rail against. In March legislative and municipal elections, 70 percent of voters defaced their ballots or stayed home rather than vote for either FMLN or ARENA, indicating that for the first time in decades, they’re looking for a third way. Former San Salvador Mayor Nayib Bukele, an anti-establishment, millionaire millennial and 2019 front-runner, backed the March boycott, although voters may not have needed the encouragement: Murders are on pace to average ten per day in 2018, nearly 80 percent of Salvadorans believe state security policies are ineffective, nearly 65 percent say police are violating human rights, and confidence in elections is at its lowest point in decades.

The Salvadoran political establishment’s hardline approach to gangs is supported by the U.S. government, which opposed gang negotiations even under President Obama, but has become a still stronger force against compromise under the Trump administration. In the past two years, the U.S. has deported thousands of Salvadorans, providing both new recruits and new targets for the gangs. The Trump administration has also threatened steep cuts in funding to El Salvador and other countries unless they do more to go after purported gang members, and threatened to choke off aid altogether unless they stop certain migrants. Trump’s lawyer, Rudy Giuliani, served as a “get-tough” security consultant to the Salvadoran government in 2015, and his chief of staff, John Kelly, formerly head of U.S. Southern Command, has long advocated for more support to “professionalize” Central American security forces, despite evidence of human rights violations.

All of this could end up empowering both El Salvador’s Evangelical movement and its criminal groups, which cater to poor and oppressed Salvadorans, including those fleeing to, and deported from, the United States. But whether the churches can use their increasing power to stabilize the country is far from clear. As Taber’s own history shows, not every attempt to spur negotiation has produced progress toward peace.

As civil war erupted in El Salvador in the 1980s, Toby Jr. was working at a Miami McDonald’s and racing motorcycles. Now forty-nine with a salt-and-pepper goatee, he still speaks English like a Miami teen, favoring “like” and “Can you imagine?”

His father was ordained in 1975 at Tennessee Temple University, then brought his family back to El Salvador to found his own congregation. But at 17, a rebellious Toby Jr. left for Florida to join his U.S.-citizen sister and mother.

By the time peace accords were signed and the prodigal son returned, Taber’s empire extended to a Bible academy, an orphanage, a rehab center, soup kitchens, and deportee services. With tattoos, piercings, boots and cargo pants, Toby Jr. publicly butted heads with his more conservative father, making no secret of his impatience for him to step aside and turn Taber’s empire over to a younger, more forward-thinking leader. When he died, the legislature held a moment of silence, and Toby Jr. inherited more than 30 ministries and 500 pastors.

I asked Toby Jr. how he felt about Trump’s attitude toward El Salvador and Latino immigrants. (Trump began his presidency talking about “bad hombres,” and “criminals,” and later moved on to talk of “shithole countries” and “animals.”)

“We’re

always blaming Mr. Trump,” Toby Jr. said. “But I always tell them, ‘The God the

Americans have is the same God the Salvadorans have. Now what is the

difference? You’re making the wrong choices.’”

Years before his father’s death, Toby Jr. began cultivating his own following—and invited controversy for giving gang leaders a platform at Taber.

In 2012, FMLN President Mauricio Funes privately gave his defense minister approval to pursue a truce with the gangs. Raúl Mijango, a former-guerilla congressman, and Fabio Colindres, a right-leaning Catholic bishop, became the primary negotiators. Under the deal, MS-13 and two Barrio 18 factions would lower homicides, and the government would transfer their leaders from maximum-security to lower-level prisons where they could enforce the truce.

Enter Toby Jr. A year into talks, as Toby Sr. was recovering from a stroke, his rising celebrity pastor son stunned Salvadorans by hosting incarcerated leaders from MS-13 and Barrio 18 before 7,000 congregants at Taber’s main church, as well as a national-TV audience. Under high security but without handcuffs, they sat next to each other in slacks and shiny shoes.

“They’d kill each other in a heartbeat! And I sat them down in church with a Bible,” Toby Jr. recounted.

In

the Taber interview with Toby Jr., the gang bosses told voters to boycott

candidates who opposed negotiation with the gangs. Afterward, they returned to

jail. Today, Toby Jr. insists that cabinet officials asked him to invite the

pair. If they did, they clearly didn’t anticipate the outrage from a

public long terrorized by gangs. After the event, the chief of prisons was promptly

dismissed, and as a backlash began in the polls, presidential hopefuls quickly

disavowed any deal with such criminals.

“Guess who got stuck with all the scandal? Me,” Toby Jr. said, insisting of the gang leaders, “I didn’t wash their feet, I didn’t give them Communion, I didn’t kiss them. They were just using us.”

As the truce’s prison transfers began, President Funes denied any quid-pro-quo, while the Catholic hierarchy declared its opposition, and the U.S. Treasury, which designated MS-13 a transnational criminal organization, added MS-13 leaders to its “kingpin” list. Subsequent reports and court testimony revealed that the incarcerated truce-participating gang leaders received everything from fried chicken and flat screen TVs to exotic dancers. Then evidence emerged that both FMLN and ARENA pledged millions of dollars to gang higher-ups to secure votes for the 2014 presidential election.

Still, the truce yielded a miracle: The homicide rate dropped by half. In 2015, when the truce collapsed, homicides spiked to a record 103 per 100,000 Salvadorans.

After FMLN barely held on to executive office amid the continued furor over the truce, newly-elected President Salvador Sánchez Cerén sought to distance himself from any association with negotiation, declaring a state of emergency in the prisons, deploying the military, and inviting extrajudicial killings of suspected gang members. The Supreme Court designated gangs and any collaborators as terrorists, and prosecutors charged dozens involved with the truce with crimes, including former President Funes.

Ahead of the 2019 contest, homicides have continued to drop from their 2015 high, but they remain among the highest in the world, and public confidence has tanked. FMLN is touting progress—but so are the gangs. MS-13 and the two main factions of Barrio 18 responded to Sánchez Cerén’s fervent crackdown by announcing a truce between themselves, independent of the state. The government can’t eliminate the gangs, a bandana-masked spokesman said, because they have the power “to destroy the country’s political establishment.”

In reality, even those claiming to offer a new path—the “anti-establishment” Bukele, for example—realize the necessity of bargaining with the gangs. Despite Bukele’s criticism of FMLN and ARENA for corrupt ties to criminal groups, his administration also made pacts with the gangs to secure projects while he was mayor, investigative site El Faro reported in June.

This is the legacy of the truce: Whatever Trump’s threats, the Salvadoran public, politicians, pastors and pandilleros all know that the road to the country’s salvation runs through gang turf.

In the crowded cafeteria at Taber’s headquarters, Charlie and Manuel, who work as janitors at the megachurch six days a week, quietly told me they’d both come from gang life. Charlie had joined when he was just 11, and each served several stints in El Salvador’s overcrowded prisons.

“Daddy, this is the first birthday you’re here with me,” Charlie’s daughter told him on her ninth birthday. At that, he decided to leave the gang and turn to God, he said.

Both asked that only their first names be used, for protection against reprisal from the gangs and the police. They’re only two of scores of gang converts as desistance continues to spread across El Salvador, but they remain vulnerable.

For a 2017 State Department report, Cruz interviewed nearly 1,200 current and former Salvadoran gang members. Roughly 60 percent said they’d gotten out or were getting out, and almost all said church was the best way. But whether conversion is sustainable is less clear.

“You need the country to create secular opportunities for its young people,” Cruz said—a view echoed by many experts.

Salvadoran and American officials believe gangs are using the Evangelical church as a front to grow their political capital. The reverse could also be true. “The cynical view is they [evangelicals] are getting involved in conversion of gang members in order to not only get political power, but also economic power,” Cruz said.

Increasingly aggressive police actions against the gangs have ensnared many civilians, even pastors—evidence some see as an important caveat to the hope placed in the Evangelical church. In a 2016 operation, authorities issued more than 100 warrants, including for Marvin Ramos Quintanilla, a former-gang-leader-turned-pastor. Prosecutors said Ramos led a double life, using a nonprofit network of Evangelical pastors to facilitate his role as MS-13’s CFO.

The network’s director, Pastor Nelson Valdez, told me that Ramos never used his chaplain credential to conduct MS-13 business. Following Ramos’s arrest, Valdez’s wife suggested he stop working with former gang members, but he hasn’t. “We have to make gangs and police better understand each other,” he said.

The police, and even Ramos’s fellow pastors, sometimes see it differently. Toby Jr. pointed to Ramos’s case as evidence that the gangs have corrupted the Evangelical community. Despite his pride in Taber’s gang converts, he estimates only a fifth of them overall are genuine.

The Salvadoran police seem to share the view. Cops still harass Charlie, now working at his Taber janitorial job, telling him, “You’re a murderer.”

“They see my tattoos and they see me as who I was, not who I am,” he said. “The civil war ended, but blood is still being shed in the streets.”

The next day, outside the thick haze of central San Salvador, Taber’s truck lurched to a stop, and a troupe of preachers clambered out, leaving gleaming Bibles and plastic bags of powdered milk in the flatbed. The steep street was hot and empty, and Brother Borja turned his sunglasses toward an alley that disappeared into colorful homes with corrugated-metal roofs.

“They will come,” he told me.

They did. Older women, young mothers, kids on their own. The crowd wordlessly formed an arc in front of Borja and the preachers. After prayers, the preachers distributed the milk and Bibles, and Borja offered to show us a view of the neighborhood. At the top of the hill, he extended a hand in greeting to two young guys who’d been standing watch—the exchange a tacit permission from the gang lookouts for the preacher to enter.

From the overlook, cinder-block houses built on an old municipal dump disappeared into the capital’s smog. Every narrow street was controlled by gangs, and below, people scattered at the sight of strangers where simply wandering onto the wrong block could be deadly.

Borja called down to a young man who looked up, holding one of the shiny Bibles just given out. Borja gestured for him to display the book, apparently for a photo op. Obliging the pastor, he raised the Bible up, but used it to cover his face.

Reporting for this article was funded by the International Women’s Media Foundation.