No matter when, or how, Donald Trump leaves office, he will have dramatically remade the federal judiciary. His administration has struggled to achieve its goals on health care, the border, and infrastructure—but succeeded all too well with the courts. Trump took office with 105 vacancies in the federal district and appellate courts, almost twice the number Obama had in 2009, and Republicans have rushed to fill them, installing more than 50 judges. The impact of these jurists will be lasting; on the circuit courts, they are on average just 49 years old.

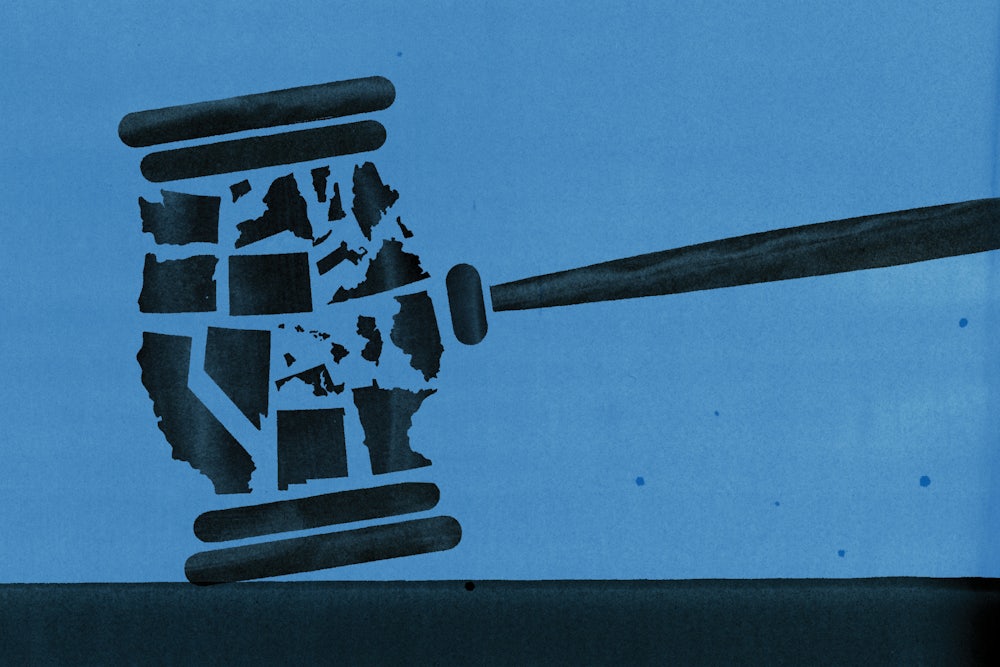

Whatever Trump does at the federal level, Democrats still have a fighting chance in the states. Neither Congress nor the president can control the selection of state judges. Term limits and regular elections make them more responsive to popular sentiment than their federal counterparts, who remain in office for life. (Until his death in August, there was a federal judge nominated by JFK on the bench.) This means that even in states like North Carolina, which Donald Trump won in 2016, there can still be a liberal majority on the Supreme Court; and crucially, their decisions are rarely overturned by the federal Supreme Court, which typically avoids interpreting state constitutions.

Some Democrats seem to understand the opportunity this presents. “Everything from family law to much of criminal law to our education system here has been affected by a decision of the state Supreme Court,” said Anita Earls, a civil rights lawyer running for a seat on North Carolina’s top court. Those courtrooms may soon be among the last remaining venues in which to pursue a liberal legal agenda. “The state courts are going to be a place where we’re going to be fighting about all of the issues that are important to people’s liberty, people’s equality,” said Samuel Bagenstos, a law professor from Ann Arbor, Michigan, who is running for the Supreme Court there.

In some states, they already are fighting. In Massachusetts last year, the court ruled that state and local police could not detain immigrants solely to buy time for federal law enforcement to take them into custody. In Pennsylvania this past January, the Supreme Court forced the state to redraw its congressional map, which was so gerrymandered, the justices wrote, that it “clearly, plainly, and palpably” violated its constitution. And in Iowa, in June, the state Supreme Court ruled that “reproductive autonomy” was protected under the state constitution, meaning that abortion would be legal in the state even if Roe v. Wade were overturned.

A more liberal judiciary in other states could make similar rulings possible. While the Michigan Supreme Court has handed down staunch conservative rulings in recent environmental and labor cases, its ideological balance could shift this November, if Bagenstos and one other liberal can win. In Texas, three seats on the Supreme Court are also on the ballot, and if a single Democrat is elected, he or she would be the first liberal to sit on the court in 24 years. Two Democratic candidates for seats on Ohio’s Supreme Court could provide a vocal liberal minority to challenge conservative rulings on voter suppression and gerrymandering. And in April, Wisconsin elected Rebecca Dallet, a candidate backed by state Democrats, to its Supreme Court, which until now has consistently ruled in favor of Republican Governor Scott Walker’s agenda on such issues as public sector unions and his own recall election.

Meanwhile, some states are considering amending their constitutions to address issues that federal courts, now that they are increasingly conservative, won’t address. Florida, for instance, will vote on a major amendment to end felon disenfranchisement, a racially discriminatory practice that the U.S. Supreme Court has repeatedly upheld as constitutional. If the amendment passes, and the measure is challenged legally, the state Supreme Court, no matter its political leanings, would have to expand ballot access. Colorado, Michigan, and Utah have also advanced state constitutional amendments that, if implemented, would allow independent commissions to redraw gerrymandered districts instead of state lawmakers—a key issue as legislators prepare for redistricting after the 2020 census. And Hawaii’s voters will even decide whether to hold a convention to rewrite their state’s constitution in its entirety.

Republicans understand the stakes and in some instances have resorted to extreme measures to take, or retain, control of the state courts. In August, the West Virginia House of Delegates voted to impeach all four sitting justices on the state’s highest court. Lawmakers defended the move as an effort to restore good government—the justices were accused of lavish and ethically dubious expenditures, including the purchase of a $42,000 desk and a $32,000 couch—but critics saw it as an effort by the Republican state government to seize control. (One of the justices has already retired; the other three will remain on the bench pending a trial to remove them in the state Senate, when they would almost certainly be replaced by more conservative jurists.) In North Carolina, Republican legislators went even further to take back the state court: They have added a constitutional amendment to the ballot in November that would let them pack the Supreme Court with two additional judges. If passed, it would turn a 4–3 Democratic majority into a 5–4 Republican majority.

A dogged focus on the courts is not new for Republicans. “They have made judicial appointments a priority in this country for a long time,” Bagenstos told me. “And on the other side, there has been much less attention until very recently.” Through the Federalist Society and Judicial Crisis Network, conservatives have been able to drive attention—and money—to key fights. When Trump nominated Neil Gorsuch to the Supreme Court, for example, conservative groups outspent liberals nearly 20 to one. Judicial Crisis Network reportedly spent $17 million. There are a few similar Democratic organizations, including Demand Justice, but it was founded just six months ago. Run by Brian Fallon, Hillary Clinton’s former spokesman, it has not yet weighed in on state races. As opportunities at the federal level dwindle, however, that could change.

Donald Trump’s legacy at the federal level may be assured, but the state courts are another matter. The November elections will decide the fate of the House and Senate. But state court races may prove more eventful for Democrats.