Even before Hurricane Florence made landfall in North Carolina on Friday morning, it had an impact: introducing the phrase “poop lagoon” to the nation.

As forecasters cemented the storm’s track, reporters began to warn that it was headed straight toward the heart of North Carolina’s hog farming country, where millions of gallons of pig feces was stored in uncovered pits. These man-made lakes of hog waste risked overflowing into adjacent drinking water sources if they became inundated with rain. And considering Florence’s predicted rainfall totals, they very likely would.

Overflows had also happened before, reporters noted. In 1999, Hurricane Floyd caused manure to spill “over thousands of acres of private and public lands and into the watersheds of four rivers that feed the second-largest estuary system in the nation,” according to the environmental news site Coastal Review. And during Hurricane Matthew two years ago, 14 hog manure lagoons became submerged. Drowned hog bodies were also found floating and decomposing in floodwaters in both instances, which created yet another source of potential disease pathogens.

As Florence approached, CNN, Vice News, NPR, and the Wall Street Journal all warned of a potential pig waste crisis. Less discussed, however, has been why this threat exists and persists, despite years of knowing catastrophic fecal overflows could happen during hurricanes. Surely, there are many reasons. But the most obvious is our appetites.

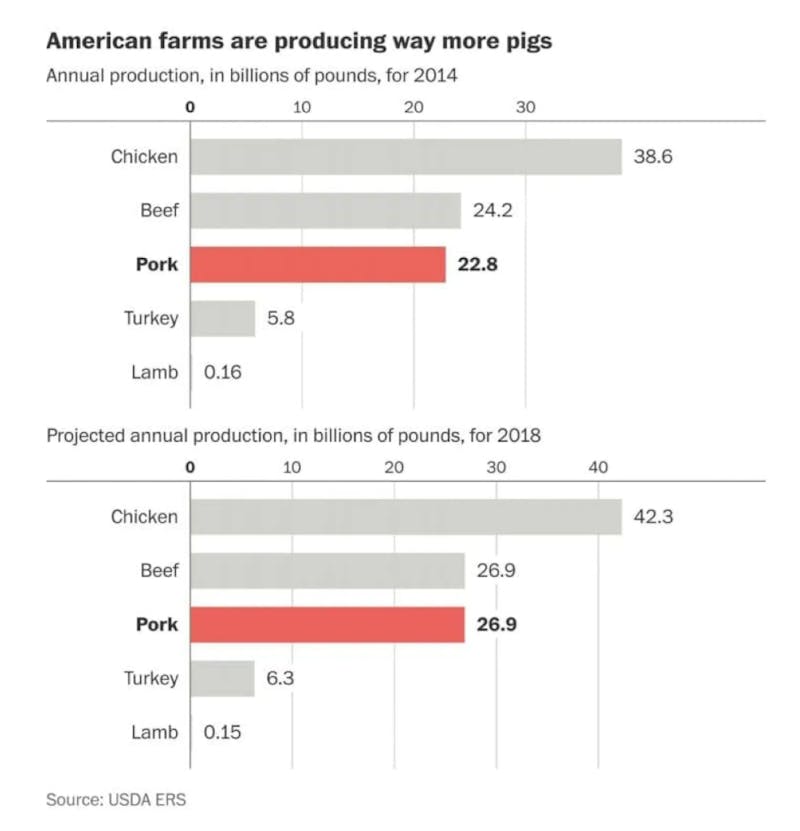

“Americans are eating more pork now than they have in decades,” the Washington Post reported last year, citing Department of Agriculture statistics showing a spike in pork production. That spike was partially because of U.S. farmers exporting pork products to other countries, the Post noted; but also because “Americans have developed a new taste for pork, particularly bacon, as well.” The growing popularity of Asian cuisines have made dishes like bulgogi and banh mi, which often include pork, “among the year’s hottest foods.” The growing popularity of low-carbohydrate diets, too, has contributed to pork’s rise. Pork production may soon outpace beef.

The growing demand for pork, both here and abroad, has been an economic boon for North Carolina. Home to nine million hogs and more than 2,000 hog farms, the state is the nation’s second-largest pork producer. And to keep that pork cheap for U.S. consumers, most of the state’s pigs are kept in concentrated animal feeding operations, commonly called CAFOs. These are industrial farming operations where more than 1,000 animals are confined for at least 45 days or more per year in an area without vegetation.

CAFOs are where the poop problem really comes from. On any type of farm, a grown hog would produce as much waste in a day as two to three grown adults. But on many of North Carolina’s hog CAFOs, as Pacific Standard recently described it, “feces, urine, and anything else that seeps beneath pens’ slatted floors—stillborn pigs, afterbirths, pesticides, blood—form a liquid slurry, which is then pumped into open-earth pits.”

In these deep pits, oxygen becomes deprived, and the waste can’t decompose as quickly. Thus, contaminants from the fecal matter “often leak into the ground,” Pacific Standard reported, citing “everything from noxious gases and heavy metals to over 100 microbial pathogens.” The manure also contains lots of nitrogen and phosphorus, which can spawn toxic algae if too much gets into nearby waterways. Nearby residents—mostly poor, and mostly African American—complain about the stench and runoff from these pits when the sun is shining. Those complaints seem like mere quibbles compared to what Florence could bring.

If American and foreign demand for pork keeps growing as it is now, the result won’t actually be more poop lagoons in North Carolina. In 2007, the state government banned waste lagoons from being built on new pig farms, in part due to the public health crisis Hurricane Floyd wrought in 1999. It does mean, however, that the old poop lagoons will remain in operation for as long as hog farmers feel they can make a profit. Considering America’s love for pork, that could be a very long time—and many more hurricane seasons.