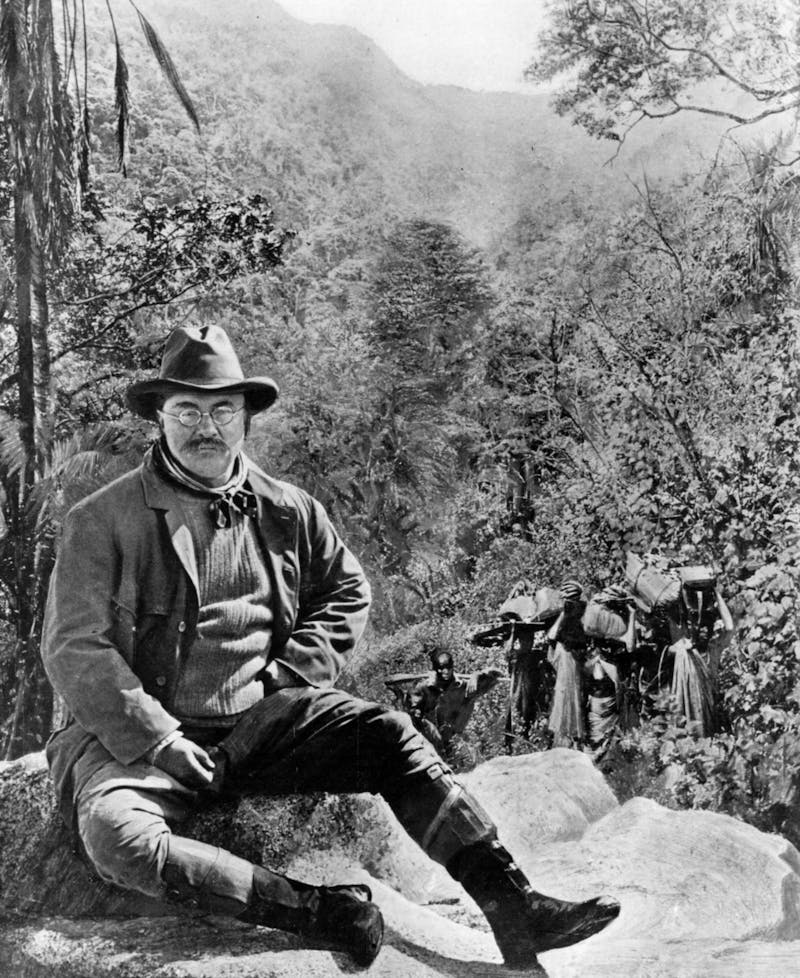

In 1909, after the end of his second term as president, Theodore Roosevelt went on safari in Africa with his son Kermit. Financed by Andrew Carnegie and a $50,000 advance from Scribner’s Magazine, the Roosevelts travelled from Kenya to the Sudan, sending back samples to the Smithsonian as they went. The African porters gave the paunchy ex-President a mocking nickname, Bwana Tumbo (“Mister Stomach”) in Swahili. When he overheard and asked what it meant, they told him it was “the man with the unerring aim.” Perhaps the joke was also metaphorical, since Roosevelt did have quite the appetite—and stomach—for shooting things. By the end of the trip, he and Kermit had personally bagged 11 elephants, 17 lions, and 20 rhinos.

A century ago, these hunting exploits made Roosevelt the toast of the American press—a reaction that is hard to understand today, when social attitudes toward trophy hunting have sharply reversed. As for attitudes toward hunting more generally, the picture is complicated: Some 70 percent of Americans say they approve of it, but only a small proportion now regularly do it themselves—around 12.5 million a year. Meanwhile, the cultural politics of hunting have become thornily intertwined with debates over guns and gun control. Liberals frequently concede a right to bear arms for hunting (although the Constitution specifies no such thing) and conservatives often present gun ownership for hunting and self-defense as politically indistinguishable (even though many hunters support various gun control measures, and self-defense, not hunting, is now the primary stated reason for gun ownership in America).

In his lively and compelling book The Fair Chase: The Epic Story of Hunting in America, Philip Dray acknowledges these tensions, deepening and complicating them by putting them in historical context. His book offers a capacious and erudite history of the practice and meanings of hunting in American life, from settlers trapping beaver on the Colonial frontier to twenty-first century fights over land use and endangered species. If any book might possibly foster “dialogue between nonhunting lovers of nature and adherents of the chase,” The Fair Chase is it. Written with sensitivity and bracketed judgment, it describes a culture and asks questions, telling a story full of paradoxes and nuance.

Hunting in America has always been criss-crossed by social and political faultlines. Like many popular and longstanding American phenomena—from football to racing cars—hunting and its roots are simultaneously aristocratic yet plebian, aspirational and visceral all at once. On the one hand, from the start, American settlers hunted as a matter of day-to-day survival, and appropriated the techniques of Native Americans to that end. But Americans were also drawn to the glamour and cachet of aristocratic British hunting culture. This combination produced a uniquely American hunting culture that was at once cosmopolitan yet local, patrician yet democratic. And what became a core part of the American identity for some, others have strongly rejected.

In England, hunting had long been a pursuit of royal courts and wealthy nobles. Like her father, Henry VIII, Queen Elizabeth adored hunting, and did it in on horseback well into her late seventies. With a keen eye for colorful detail, Dray narrates the elaborate rituals of the English hunting tradition, and samples its rich vocabulary, from “nouns of assembly” (“a sloth of bears” or “a business of ferrets”) to nomenclature (a six-year-old stag that evades a king or queen is dubbed “a hart royal proclaimed”) to flowery euphemisms for different kinds of scat. (Bears, it turns out, do not shit in the woods: They leave “lesses”).

American elites carried on the enthusiasm for hunting of their British counterparts. Whenever he could, George Washington hunted foxes in the British manner, on horseback and with hounds. But colonial and Revolutionary America also had a different kind of hunting elite: backwoodsmen who were deadshot marksmen and who, using techniques often learned from Native Americans, became experts at hunting North American game. Through their service in the Seven Years and Revolutionary Wars, such hunters went from shaggy disreputability to celebrated icons of American self-reliance, patriotism, and mastery over nature.

Dray focuses particularly on the story of Daniel Boone, whose cultural impact he places on the same level as the Founding Fathers. Born in Pennsylvania in 1734, Boone was one of the first whites to settle west of the Appalachian Mountains, and was already a noted Native American fighter and hunter when his story first appeared in 1784. Presented as an adventurous, hardy, and straight-shooting (in all senses) frontiersman, Boone became a living folk hero, and set a template for a certain American character, one for whom hunting was a defining pursuit. (His story was in fact written by a land speculator who hoped that Boone’s example would encourage people to move to Kentucky, and boost returns on his own investment.) Subsequent larger-than-life figures, from Davy Crockett to Buffalo Bill to Theodore Roosevelt would all draw, in different ways, on this archetype.

Whether in cheap broadsheets or erudite philosophical meditations, American writers were instrumental in building up the legendary status of many more figures like Boone. For literate audiences, such stories reinforced a sense of national confidence, and connected urban dwellers with the frontier as America expanded. They also presented hunting as an activity that mixed the “earthy charms” of rustic life with the “manly bonhomie” of aristocratic recreation. A generation before Mark Twain, early nineteenth-century newspaper writers regaled their readers with frontier tall-tales like “Chunky’s Fight With the Panthers” and “How Sally Hooter Got Snakebit.” In this same period, Henry William Herbert, a prodigal son of the British aristocracy turned New York sports writer, adopted the pen name “Frank Forester” and produced an immensely popular series of lightly fictionalized stories about expatriate British gentry hunting in the forests of Warwick, New York.

As America industrialized and middle-class workers spent ever more time in stores and offices, hunting was increasingly presented as an opportunity for healthy, character-building return to nature. “Out upon these scholars!,” proclaimed Ralph Waldo Emerson, “with their pale, sickly etiolated indoor thoughts! Give me the out-of-door thoughts of sound men, thoughts all fresh and blooming.” Emerson himself was a hunter, going in the 1850s on regular excursions to the Adirondacks organized by landscape painter William Stillman, in which Oliver Wendell Holmes, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and naturalist Louis Agassiz also joined.

The fundamental appeal of hunting stories, Dray observes, is the core “unique narrative power” of the hunting story as a genre itself. A quarry is pursued, and challenges are met. It is hard to imagine a more basic (or concisely compelling) formula. Yet the appeal of such stories was far from universal: Some Americans have long had moral scruples about killing animals for sport—and for many Native Americans, wanton hunting by whites was quite literally an existential threat.

As the nineteenth century proceeds, and America’s frontier expands, Dray’s cast of characters multiplies. Big-game-crazed European nobility undertake lavish expeditions in the American West, hunting not just exotic animals but occasionally more idiosyncratic (emotional and sexual) goals as well. Pioneers, hunters, and cowboys make their names—Texas Jack, Calamity Jane, and Bill Hickock, among others—and become dime-novel celebrities. Some scenes are surreal, as when the Romanov Grand Duke Alexis, son of Czar Alexander II, hunts on the Great Plains alongside Buffalo Bill and Colonel George Armstrong Custer. Others are devastating: Dray tells of a German immigrant hunter, Frederick Gerstaecker, who is puzzled by finding so many Native American remains in a Southern forest, until he realizes he is on the path the Trail of Tears:

Many a warrior and squaw died on the road from exhaustion… and their relations and friends could do no more for them than fold them in their blankets, and cover them with boughs and bushes, to keep off the vultures, which followed their route by thousands, and soared over their heads; for their drivers would not give them time to dig a grave and bury their dead.

This last episode suggests something crucial: Any story of whites hunting in America, whatever their class or ethnicity, is also story of native communities being ethnically cleansed from that same territory. Dray does not hesitate to remind the reader of this fact repeatedly.

Nor does he shy away from the frequently queasy aspects of the history he unpacks. For all its grandeur, America’s romance with hunting also reveals unpleasant truths about the country’s capacity for limitless consumption, environmental recklessness, and indifference to both human and animal suffering. Over the course of the nineteenth century, the American appetite for game meat and animal products grew almost incomprehensibly ravenous. Using massive “punt-guns” (basically cannon-sized shotguns), American hunters would down entire flocks of birds, selling them by the penny for pies (a dozen birds in each) or harvesting feathers for a lucrative trade in plumed ladies’ hats. Entire species were driven to the edge of extinction, and some, like the passenger pigeon, over it. “Market hunters” armed with high-power rifles flooded the prairies, killing buffalo at rates as fast as a hundred buffalo per man per hour; tourists sniped buffalo for the thrill of it from stopped trains and then left the carcasses to rot. William T. Hornaday, the first director of the Bronx Zoo and a founding father of American wildlife conservation, documented a loss of fifteen million buffalo from 1867 to 1887.

The loss of these species sparked movements for conservation and against animal mistreatment, from the Audubon Society to the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Sports hunters themselves led much of this groundswell of activism, since they had not only witnessed the ravages of extinction firsthand, but also had a sincere interest in maintaining wild spaces and animal populations for their own use. Indeed, it was largely the efforts of organizations like the Boone and Crockett Club (founded in 1887 by Theodore Roosevelt) that built the political momentum to create the National Park System and enact legislation creating hunting seasons and protecting migrating birds. Hunters and hunting activists formally put forward the idea of a “Fair Chase,” a set of rules stipulating supposed sportmans-like conduct towards game. And the Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act of 1937, known as the Pittman-Robertson Act, established an 11 percent excise tax on ammunition and hunting gear.

All this may be surprising for some readers, particularly for those who view hunting and hunting culture with distaste. Environmentally-conscious liberals are indeed often repulsed by the idea of forming political coalitions with people who, they may argue, are interested in animals only because they want to kill them. “If a person believes it is immoral to shoot and kill an innocent wild animal,” Dray observes, “no counterargument about hunting as a means of maintaining wildlife population levels or people getting back in touch with nature is likely to resonate.” But, as Dray also pointedly notes, the anti-hunting public has often proved unwilling to pick up the conservation slack: Attempts to extend Pittman-Robertson-style taxes to other outdoors gear, like hiking supplies, have all failed.

Meanwhile, many people who oppose hunting are fairly indifferent to the fate of billions of animals kept in abominable conditions for food in factory farms, or to the wild animals inevitably killed in the production of even vegan or organic produce. “If humankind’s presence alone causes animals to die,” Dray observes, “it might lend credence to the hunter’s claim that as man is already deeply involved in animal destruction, hunting is simply its most honest manifestation.”

As The Fair Chase amply demonstrates, the cultural politics of conservation, like the cultural politics of hunting, have always been tangled. William Hornaday, the zoologist who lamented the fate of the buffalo and helped inaugurate the modern conservation movement, was also a scientific racist who put a Congolese pygmy on display in a primate exhibit, and who thought immigrants from Southern Europe were “bird-killing” vermin. And today, left-leaning environmentalists eager to oppose oil pipelines or the de-listing of National Forests must navigate a political landscape in which they may find themselves bedfellows with gun rights activists and firearm industry lobbyists.

As Dray so powerfully demonstrates, debates over conservation, like debates over hunting, have always illuminated certain core contradictions in American culture: tensions between the urban and rural, between the natural world and capitalist extraction, between elites and the general populace. The path forward, if there is to be one, seems to lie in both perceiving these tensions while working with them, one way or another. As an unrivaled history, and an admirably crafted bid to deepen dialogue between groups of Americans who might otherwise view one another as alien or out of touch, Dray’s Fair Chase is a vital intervention.