When former British foreign secretary Boris Johnson spoke out against Denmark’s burqa ban earlier this month, he made it clear he still wasn’t a fan of the veils; the women who wear the “oppressive” garments look like “letter boxes“ or “bank robbers,” he wrote in his Telegraph column, and businesses should be allowed to “enforce a dress code” on their own. Critics denounced the “Islamophobic” comments from the pages of rival publications. Veiled women also reported a spike in racist abuse on the streets after the remarks.

There’s no proposal pending to ban face veils in the United Kingdom. But there is speculation that Johnson, who has his eyes on the conservative party leadership, decided to woo his party’s base by dissing women who wear the veil in Trump-style plain-speak, while citing enough John Stuart Mill to give him some cover for the intolerant remarks. In Denmark—where only around 150 women wear the full face veil but the anti-migrant Danish People’s Party has gotten increasingly popular with voters—the center-right government’s motive for banning the niqab and burqa as of August 1 was not so different.

Earlier this year, the Open Society Foundation published a study that found that 22 out of 28 European Union states are currently debating some kind of legislation regarding Muslim women’s clothing. Mainstream political parties introduced most existing bans after 9/11 amid rising Islamophobia. But the current rash of burqa-ban proposals have largely been championed by far-right parties, whose numbers have swelled due to rising immigration from Turkey, North Africa and the Middle East, especially during the migrant crisis in 2015. Now, more moderate parties are increasingly incorporating elements of far-right platforms into their own agendas.

Facing a hot-headed far-right opponent in 2017, for example, Austrian chancellor Sebastian Kurz drafted an integration packet that included banning full face veils. As in Denmark, very few women are estimated to wear the Islamic veil in Austria. But it is precisely because so few women wear the burqa or niqab in European countries, according to Maryam H’madoun at the Open Society Justice Initiative, that certain centrist politicians think it’s fine to stir up resentment against the women who wear these garments. “They think that the gains in appeasing far-right voters are higher than the losses,” H’amdoun says, “and that they are not really hurting Muslims, because so few women are affected.”

But H’madoun’s research suggests that this is not the case. “Once you have one regulation, it opens the door to other regulations,” she says, including by non-state institutions. A few years after Belgium passed a national ban on the burqa and niqab, a Belgian ice cream parlor saw fit to enact its own mini-ban on customers wearing headscarves.

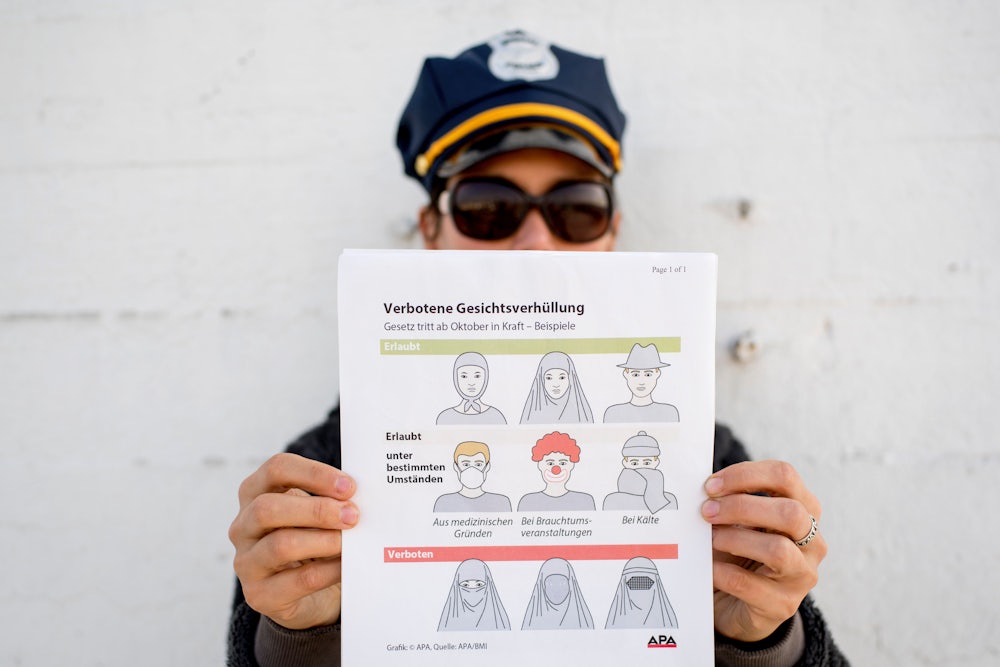

Because their governments don’t want to be sued for religious or racial discrimination, countries like France, Denmark, Belgium and Austria have formally banned all “garments that cover the face in public.” In 2014, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that a French law along these lines encouraged people to “live together,” and was in fact legal. But so far, Austria looks to be the only one of those countries where the police were given clear instructions to enforce this law in a non-discriminatory way. And as a result, since last October, only one woman has been charged for wearing the full face veil, on four separate occasions. The others who were stopped included people in animal costumes and a young man with leukemia who was almost forced to remove his medical mask.

Seemingly unimpressed by the results thus far, Sebastian Kurz’s new government is now trying to pass a ban on headscarves in kindergartens, despite there being no evidence that this is an existing problem. Austria’s states are less than thrilled about the difficulties that will come with enforcing this new “symbolic act.” The country’s biggest tabloid paper, the Kronen Zeitung, which prides itself on not being politically correct (or, as Schmitt puts it, “offering reality, even when it worries people”), has struggled to find concrete evidence of children under the age of 10 wearing a headscarf in Austria’s childcare institutions.

“I have no personal interest in the subject of headscarves,” said Kronen Zeitung’s digital editor-in-chief Richard Schmitt, speaking on the phone from his office in Vienna. “But headscarves in kindergartens are a topic that our users like to discuss with us.”

Back in last year’s pre-election summer, Schmitt personally wrote an article about an “Islamic kindergarten“ in Vienna where “fully veiled mothers drop off the small ones” and “even small girls have to wear a headscarf.” But it turned out Schmitt’s evidence of this trend consisted of two photographs taken not at a kindergarten, but at a youth festival that been hosted by a mosque on the other side of town one year earlier. In the original pictures, there were also young girls not wearing headscarves. To fit the story, Schmitt’s team cropped them out. Schmitt was unembarrassed when I asked him about the erroneous “Islamic Kindergarten“ story. He admitted that he had given the wrong location and place and time, but claimed that he “didn’t want to stir up hate” against the mosque that organized the festival whose online photos he had ripped off.

Two years earlier, the Kronen Zeitung published a picture of some young kids standing next a woman wearing a niqab, under the headline “Teacher in a niqab.” The woman was actually one child’s relative, visiting from Egypt.

For Carla Baghajati of the Austrian Islamic Religious Community in Vienna, the Austrian government’s current plan to ban headscarves in kindergartens—and maybe schools as well—is an insult. Baghajati has worked for years helping parents to support daughters who wish to wear a headscarf in a way such that they also feel free to take it off again if they change their minds. Now, Baghajati says, “Parents are asking: is the state trying to signal to the majority that they can make the Muslims raise their children properly? That they can protect Muslim children from their own parents?”

Whatever the motives behind European “burqa bans,” there is little evidence to suggest that co-opting a far-right party’s agenda will weaken it. Some Austrian politicians today point to Sebastian Kurz as the poster boy for taming the far right. But they forget that ahead of the Austrian elections last year, it was already clear that one of the two centrist parties would end up in a ruling coalition with the far-right Freedom Party. Far from “taming” the extremists, Kurz merely moved toward his future right-wing coalition partners somewhat ahead of schedule. Meanwhile, this fall in Germany, mimicking the far right ahead of Bavaria’s state elections only made the German Christian Social Union more unpopular in the polls.

Nor do these bans usually come alone. In Denmark, the government also recently passed a law that requires children who live in immigrant “ghettos” to receive instruction in “Danish values.” Meanwhile in Austria, the noise around a headscarf ban and prohibition on kosher-halal meat has helped distract from the newly right-wing government’s raid on its own intelligence service, widely presumed to have been a politically motivated move.

As in the United States, anti-Muslim and anti-immigration measures are popular in certain circles, and praised in very specific media outlets. Richard Schmitt doesn’t think it’s a problem that his newspaper’s stories neatly overlap with the social media posts of Sebastian Kurz and his vice-chancellor. “I would be just as happy if the left were to share our articles,“ he giggled. “But unfortunately their minimally popular social media account is still being run by the Social Democrat press office.”

If anything, the backlash against Boris Johnson’s column showed that Britain has not yet succumbed to the idea that anti-Islamic far-right attitudes should become mainstream. Whether that will persist if Johnson succeeds in his scheme to become prime minister is an open question.