“Beach, eat, drink, dance, repeat.” These are Rihanna’s favorite things to do in Barbados. In a June 7 interview with Conde Nast Traveller, the pop star gushed over her home country, a small island nation in the middle of the Caribbean. “When I’m in Barbados, all is right with the world,” she said. But not all was right with Barbados.

The same day, the local The Daily Nation newspaper reported on an “invasion of the Sargassum seaweed”—a brown, leafy algae that had washed up in thick mats on the white-sand beaches of the island’s eastern shores. The next day, the country’s government declared it a national emergency. Seen from afar, the bloom looked like a coppery oil spill slicking the sea. But a closer look revealed dead wildlife entangled within it.

The June Sargassum invasion in Barbados claimed the lives of three sea turtles, six dolphins, and “countless” fish and eels, The Daily Nation reported. But surely more have perished in the months since, as sheets of the bulbous-tipped seaweed—sometimes several feet deep—have become regular visitors to the country’s eastern and southern shorelines.

“We’ve had mass mortality of sea turtles that have gotten trapped under ever-thickening piles,” said Hazel Oxenford, a Barbados-based fisheries biologist at the University of the West Indies. “When the turtles try to come up for air, they drown.” Because these Sargassum beachings are primarily happening during nesting season, which runs from March until the end of October, baby turtles attempting to crawl from their eggs toward the ocean are also getting caught in it.

Barbados isn’t alone. In the last six months, more than 700 beaches across the Atlantic Ocean, Caribbean Sea, and Gulf of Mexico have been hit with mass beachings. Mexico, Belize, Guadeloupe, Martinique, and the British Virgin Islands are covered in it, taking a toll on tourism and fishermen alike. “The fishermen could not go to sea for two or three days,” a worker in Dominica told Hakai Magazine. “They couldn’t get the boats out because it was so thick.” South Florida, too, has seen an “assault.” It’s the worst year for Sargassum beachings ever.

There’s not a lot of history to trace, though. Sargassum algae only started becoming a real problem seven years ago. The true origin of these mass invasions, and the cumulative impacts of them, are thus not fully known. Some experts speculate there could be positive impacts along with the negative ones. But much of the story of this new phenomenon remains a mystery.

Sargassum researchers do appear confident in two things, though. The first is that these algal blooms constitute a new type of natural disaster—one that, like hurricanes, can be expected every single year. The second is that this new risk is not entirely natural. Humans have made these blooms far more likely.

There are more than 100 different species of Sargassum in the world, but two types in particular keep popping up on Caribbean beaches: Sargassum natans and Sargassum fluitans. Unlike most other types of seaweed, which begin life attached to the ocean floor, these species reproduce vegetatively on the ocean’s surface. They’re also thought to originate in the Sargasso Sea in the North Atlantic, the only named sea that never touches land; it’s bound only by ocean currents, leaving the sea itself relatively still.

The floating mats of Sargassum within the Sargasso Sea are so vast and thick, they often look like land masses. Out there, that’s always been a great thing. As the National Ocean Service explains, Sargassum mats provide “essential habitat for shrimp, crab, fish, and other marine species that have adapted specifically to this floating algae.” Threatened and endangered eels, sharks, and dolphinfish spawn there; birds use it for food. Commercial fish like tuna also feed on the algae, making the Sargasso Sea a fisherman’s dream.

Problems with Sargassum only started to arise in 2011. Seemingly out of nowhere, the seaweed began to amass in huge quantities on “beaches across the Caribbean, trapping sea turtles and filling the air with the stench of rotting egg,” according to a report in the journal Science. The foul odor stems from hydrogen sulfide, which the seaweed releases when it rots on land.

The 2011 event was originally considered a freak occurrence. “We thought it was all over,” Oxenford said. “But it came back in 2014, and then again in 2015 in a big way, and it spread much further.” This year, the Sargassum onslaught has stretched out over more than 1,000 square miles of the Caribbean Sea alone. And it’s not the only sea affected this year, according to a map of 2018 beachings.

Where did it all come from? Naturally, scientists originally assumed the Sargasso Sea. But in 2016, a team of researchers published a paper asserting it came from a huge patch of Sargassum floating in the tropical Atlantic, east of Brazil. “None of it ever tracked northward into the Sargasso Sea,” University of Southern Mississippi marine biologist James Franks, who worked on the paper, told Science. He believes ocean currents are sweeping this new source of Sargassum up the Brazilian coast toward the Caribbean.

Brian LaPointe, an algal bloom expert at Florida Atlantic University, said he also believes the tropical region near Brazil is the nursery from where it all came.* His research asserts the seaweed has a “dynamic existence,” continually moving from the equatorial currents toward the Caribbean and the Gulf Stream, with some eventually settling in the Sargasso Sea.

LaPointe considers all the Sargassum beaching events to be part of one big algal bloom: “The largest harmful algal bloom on our planet,” he said. And if he knows one thing about algal blooms, it’s that they thrive off of two things humans keep putting into the ocean: heat and nitrogen.

More studies will be required to fully understand Sargassum’s rapid spread, but a growing number of researchers feel comfortable pointing to humans as a culprit.

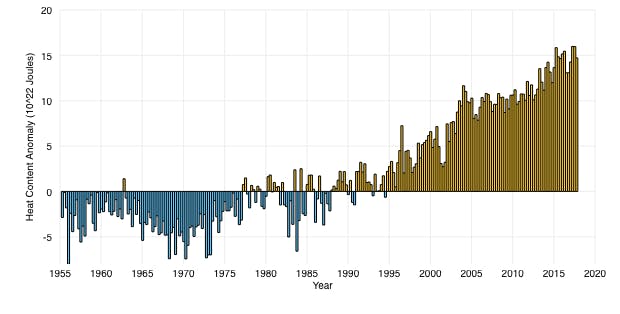

“This is another symptom of climate change and ocean pollution,” Oxenford said, pointing to how humans have warmed the ocean. As InsideClimate explains, “More than 90 percent of the excess heat trapped by greenhouse gas emissions has been absorbed into the oceans that cover two-thirds of the planet’s surface.” In particular, the heat content of the ocean surface—where Sargassum grows—has increased dramatically since the 1950s. A 2017 study published in Biogeosciences cites “high anomalously unprecedented positive sea surface temperature” as a potential factor in the blooms.

Lew Gramer, a marine scientist at the University of Miami, has also described a possible “correlation” between climate change and Sargassum’s spread due to changes in ocean circulation. “An unusual pattern of winds and ocean-surface circulation over the Sargasso Sea in late 2009 and early 2010 preceded the first mass beachings,” he said. “And this pattern actually coincided with an anomaly in a sea-level air pressure index that is also studied by climate scientists, the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO).” Some researchers have linked changes in the NAO to global warming.

Another factor appears to be nitrogen, which humans have continuously poured into the ocean via fertilizer runoff and overflowing sewage systems. Nitrogen pollution is widely known to feed algal blooms, including Sargassum, and is a possible cause of the red tide plaguing the Gulf coast of Florida.

The main source of this pollution is still in dispute. The 2017 Biogeosciences study, for example, asserts the pollution responsible came from agricultural runoff into the Amazon River, as well as “deforestation, agroindustrial and urban activities in the Amazonian forest.”

LaPointe, however, believes the Sargassum infestations are fed by all land-based nutrient pollution—from the Amazon, but also the Congo and the Mississippi, among other places. “We have greatly altered the nitrogen cycle on this planet,” he said, adding that local sources of nutrient pollution near Sargassum beachings are exacerbating the issue. In places like Florida and the Caribbean, those sources are most often inadequate wastewater infrastructure. “Human sewage is creating a much bigger role than anyone wants to admit,” he said.

If one thing is clear, though, it’s that the people who helped cause Sargassum’s spread are not all affected by Sargassum beachings. For Oxenford, that’s a frustrating reality. “It’s yet another man-made problem that’s been thrown at the Caribbean that isn’t our doing,” she said. But if the Caribbean and other affected areas are to thrive, they must figure out how to fix it—or at least prevent it from causing more damage.

Nancy Jones Peterson has seen the impact of Sargassum beachings up close. Earlier this summer, as she walked the beach at Phipps Ocean Park in Palm Beach, Florida, she came across a small but thick mat of brown algae. The registered nurse took a closer look, and found three dead baby sea turtles.

“There they are,” she said in a video posted to Facebook, her voice shaking. “The poor babies tried to get out to the ocean, and all these seaweed—caught up in the seaweed and they didn’t make it out.”

The Barbados Sea Turtle Project has been documenting similar discoveries on its Facebook page. In one video, a woman digs out an adult turtle from a pile of Sargassum even taller than she is.

This phenomenon has Oxenford particularly worried about the health of local marine environments. “As the seaweed stats to rot, the bacterial population grows enormously and you have huge oxygen demands,” she said. “It starts suffocating organisms.” The thickness of the seaweed mats also block sunlight from getting to sea grass and corals, threatening those organisms, too.

But Oxenford is adamant that not all is lost for local marine life or the tourism and fishing industries. Far from it. “We still have our sunshine and our clear water and beaches with no sargassum,” she said.

Due to ocean currents, Sargassum beachings are also only really happening on eastern and southern parts of Caribbean islands; the western and northern shores are clear. Sea turtle populations overall should be able to survive the beachings, as many nesting sites are not on affected beaches. Some tourist towns in Mexico have installed floating barriers to keep the seaweed from washing ashore. The U.S. has sent two Sargassum boats to help with cleanup in Quintana Roo region of Mexico, which includes Cancun and Playa del Carmen.

“I see this as a solvable problem,” Oxenford said. But not solvable in the sense that the Sargassum will ever go away. “It’s the same way hurricanes are not solvable,” she said. “But we’ll learn to live with it.” Living with it will require a new system where algal blooms are treated like hurricanes. Blooms will be predicted and forecasted, with different levels of alerts to denote the scale of the Sargassum event. Countries will need to implement management and response plans—and fund them appropriately. Ideally, Caribbean countries won’t have to pay for all of it, since they’re aren’t solely or even largely to blame for it.

It’s a daunting task, for sure, but Oxenford isn’t alone in looking at the silver lining. On a different walk on the beach a few days later, Peterson found another sheet of Sargassum—this one containing whole nest of dead hatchlings. “Around 50 to 100, they were all in the seaweed,” she said.

But this time, one was moving. There was no time to waste. Immediately, she said, she took it to the Loggerhead Marine Life Center in Juno Beach, where it she was told it would be rehabilitated and released. Her video from that day has a happy ending.

*Correction: A previous version of this story incorrectly described Brian LaPointe’s research on the origin of massive Sargassum blooms. He does not believe they originated in the Sargasso Sea.