On a frigid December day in 2017, Oleg Kalugin opens the door of his house in Rockville, Maryland, an upper-middle-class suburb of Washington, D.C., to meet me. Nothing in particular distinguishes his split-level suburban home from those of the other professionals in the neighborhood, but the man who lives there is very much out of the ordinary, a former KGB spymaster who is now an American citizen.

Born in St. Petersburg (then Leningrad), Kalugin, at 83, now lives just half an hour’s drive from the White House, which for decades was dead center in the crosshairs of the KGB, the dreaded secret security forces he served as head of counterintelligence. A genial host, Kalugin gives a guided tour of his sprawling library spread over three rooms and reveals himself to be a man of history, a veritable Zelig of the Cold War.

When it comes to Soviet leaders Yuri Andropov, Mikhail Gorbachev, and Boris Yeltsin, Kalugin knew them all and can regale you for hours with stories about them. He was even the boss of a promising young KGB officer named Vladimir Putin.

Of medium height, immaculately groomed, clad in dark blue slacks, a striped shirt, and a light blue jacket, Kalugin was congenial and utterly disarming when I met him. As John le Carré wrote, when he interviewed Kalugin nearly 25 years ago, he is “one of those former enemies of Western democracy who have made a seamless transition from their side to ours. To listen to him you could be forgiven for assuming that we had been on the same side all along.”

Kalugin is of special interest these days because his experience as head of counterintelligence for the KGB makes him a master of the tradecraft that was used to ensnare Donald Trump. The operation began during a 1978 trip to Czechoslovakia not long after Trump’s marriage to Ivana, in which the newlyweds piqued the interest of the Czech Ministry of State Security (also known as the StB) enough that a secret police collaborator began observing Ivana and met several times with her in later years.

Keeping tabs on Czechs who had left the country was standard operating procedure for the StB. “The State Security was constantly watching [Czechoslovak citizens living abroad],” said Libor Svoboda, a historian from the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes in Prague. “They were coming here, so they used agents to follow them. They wanted to know who they were meeting, what they talked about. It was a sort of paranoia. They were afraid that these people could work for foreign intelligence agencies. They used the same approach toward their relatives as well.”

According to the German newspaper Bild, starting in 1979, encrypted StB files say, “the phone calls between Ivana and her father were to be wiretapped at least once per year. Their mail exchange was monitored.” The agent who reported on Ivana used the code names of “Langr” and “Chod.” The StB files are stamped “top secret,” bear the code names “Slusovice,” “America,” and “Capital,” and indicate an ongoing attempt to gather as much information about Trump as possible.

“The StB thought there was a chance that the U.S. intelligence agencies could use (Ivana Trump). And also they wanted to use Trump to gather information on U.S. high society,” said Svoboda.

The StB archives also show that Ivana’s father, Miloš Zelníček, was monitored by the secret services and that during his 1977 trip to the U.S. for Ivana’s wedding, Zelníček was subject to an StB-ordered search of his possessions at the airport. “He provided information that the secret police found out anyway from other sources,” said Petr Blažek of the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes, who suggested that the search was a warning shot telling Zelníček that cooperation was the only way such trips would be permitted in the future.

Far from handing over compromising materials, Zelníček may have simply delivered the minimal amount of information necessary to keep the StB off his back. “Ivana’s father was registered as a confidant of the StB,” Czech historian Tomas Vilimek told the Guardian. “However, that does not mean he was an agent. The CSSR authorities forced him to talk to them because of his journeys to the U.S. and his daughter. Otherwise, he would not have been allowed to fly.”

In the end, we do not know exactly when the KGB first opened a file on Donald Trump. But it would have been common practice for the Czech secret police to share their intelligence on the Trumps with the KGB. More to the point, Trump was so highly valued as a target that the StB later sent a spy to the U.S. to monitor his political prospects for more than a decade.

It’s unclear how much Trump himself knew about his in-laws’ encounters with Czech intelligence, but when Mikhail Gorbachev, the last leader of the Soviet Union, rose to power in 1985, and put forth the policies of perestroika (literally “restructuring” in Russian) and glasnost (“openness”), which eased the tensions of the Cold War, Trump became deeply infected with a severe case of Russophilia.

In the past, his participation in politics had been confined to getting his mentor Roy Cohn to push through tax abatements, changes to zoning restrictions, and the like—or making political donations to accomplish such goals. Suddenly, Trump reinvented himself as a pseudo-authority on nuclear arms and asserted that he could play a key role in strategic arms limitations.

Trump took the issue up in an interview with journalist Ron Rosenbaum in the November 1985 issue of Manhattan, Inc. magazine, in which he asserted of nuclear proliferation, “Nothing matters as much to me now”—an extraordinarily unlikely passion for a man who personified conspicuous consumption.

Trump started by telling Rosenbaum about his late uncle John Trump, an MIT professor, who explained that nuclear technology was becoming so simplified that “someday it’ll be like making a bomb in the basement of your house. And that’s a very frightening statement coming from a man who’s totally versed in it.”

What was taking place was decidedly un-Trumpian. Rosenbaum, who was anything but a Trump enthusiast, said the real estate developer “seemed genuinely aware of just how much danger nukes put the world in.” He even passed up a chance to tout the glories of Trump Tower. Instead, Rosenbaum told me, Donald Trump preferred to be seen as being in “on some serious stuff. The fact that his uncle was a nuclear scientist gave him the right to make these pronouncements.”

Trump made a similar pitch to The Washington Post. “Some people have an ability to negotiate,” he told the paper. “It’s an art you’re basically born with. You either have it or you don’t.”

Lack of confidence was not his problem. “It would take an hour-and-a-half to learn everything there is to learn about missiles,” he said. “I think I know most of it anyway.”

Which did not mean Trump was above seeking out expertise. A few months later, according to The Hollywood Reporter, in 1986, he insisted on meeting Bernard Lown, a Boston cardiologist best known for inventing the defibrillator and sharing the Nobel Peace Prize with Yevgeny Chazov, the personal physician for Mikhail Gorbachev.

After accepting their Nobel medals in Oslo, Lown and Chazov went to Moscow and spent time with Gorbachev, the new Soviet leader. Not long after he returned to the United States, Lown got a message from Trump. At the time, Lown had never even heard of him but secretly hoped Trump might contribute to the Lown Cardiovascular Research Foundation, which was low on funds at the time.

They met in Trump’s offices on the 26th floor of Trump Tower. “I arrived totally ignorant about his motives,” Lown told me. “We sat down for lunch and Trump was very grim looking, very serious.”

“Tell me everything you know about Gorbachev,” Trump said.

After 20 minutes or so recounting his experience with the Soviet leader, however, Lown became painfully aware that Trump wasn’t listening. “I realized he had a short attention span,” Lown said. “I thought there was another agenda, perhaps, but I didn’t know what that was.”

Lown cut to the chase. “Why do you want to know?” he asked Trump.

At that, Trump revealed his grand plan. “If I know about Gorbachev, I can ask my good friend Ronnie to make me a plenipotentiary ambassador for the United States with Gorbachev.”

“Ronnie?” Lown asked.

Lown was unaware that Trump had retained the powerful lobbying firm of Black, Manafort & Stone shortly after it opened shop in 1980, and its three name partners—Charles Black, Paul Manafort, and Roger Stone—had just played vital roles in Ronald Reagan’s 1984 landslide victory.

“Ronald Reagan,” Trump explained.

Then he clapped his hands together, Lown says, and went on to say how within one hour of meeting Gorbachev, he would end the Cold War.

“The arrogance of the man, and his ignorance about the complexities of one of the complicating issues confronting mankind! The idea that he could solve it in one hour!”

Thanks to Gorbachev, the Russian bear had finally put on a friendly face, but the KGB had not. It remained the most effective and most feared intelligence-gathering organization in the world with more than 400,000 officers inside the Soviet Union and another 200,000 border guards, not to mention an enormous network of informers. And that didn’t even include the First Chief Directorate (FCD), the relatively small but prestigious division in charge of gathering foreign intelligence. It had about 12,000 officers and was headed by General Vladimir Kryuchkov, a hard-liner who seemed to be swimming against the tides of history.

Gorbachev’s dovish overtures to the West notwithstanding, Kryuchkov, according to ex-KGB general Oleg Kalugin, was still very much “a true believer until the end, eternally suspicious of the West and capitalism.”

Kryuchkov is of special interest not simply because of his unreconstructed hard-line views. Thanks to a compendium of his memos during this period entitled “Comrade Kryuchkov’s Instructions: Top Secret Files on KGB Foreign Operations, 1975–1985,” we know that by 1984 he was deeply concerned that the KGB had failed to recruit enough American agents. To Kryuchkov, absolutely nothing was more important, and he ordered his officers to cultivate as assets not just the usual leftist suspects, who might have ideological sympathies with the Soviets, but also various influential people such as prominent businessmen.

And so, as if orchestrated by Kryuchkov, the political education of Donald Trump began in March 1986, when he met the Soviet Ambassador to the United Nations Yuri Dubinin and his daughter Natalia Dubinina. Dubinina, who was part of the Soviet delegation to the U.N., was an interesting figure herself in that the Soviet mission was widely known to harbor KGB agents. As she told the Russian daily Moskovsky Komsomolets, when her father arrived in New York City for his very first visit, she took him on a tour, and one of the first buildings they saw was Trump Tower on Fifth Avenue.

Natalia said her father “never saw anything like [Trump Tower], that he was so impressed that he decided he had to meet the building’s owner at once.” And so, Soviet Ambassador Yuri Dubinin and his daughter Natalia, in a highly unusual breach of protocol, went into Trump Tower, took the elevator up to Trump’s office, and paid him a visit.

It is unclear whether prior arrangements were made to set up this extremely irregular meeting between a highly placed Soviet diplomat and Trump. But a few months later, at a luncheon given by cosmetics magnate Leonard Lauder, Trump happened to be seated next to Yuri Dubinin, who proceeded to flatter the young real estate mogul shamelessly.

Trump later rhapsodized about the conversation in The Art of the Deal. “[O]ne thing led to another,” he wrote, “and now I’m talking about building a large luxury hotel across the street from the Kremlin, in partnership with the Soviet government.”

For the KGB, Kalugin told me, recruiting a new asset “always starts with innocent conversation” like this.

As Natalia Dubinina explained, the Russians were off to an auspicious start. “Trump melted at once,” she said. “He is an emotional person, somewhat impulsive. He needs recognition. And, of course, when he gets it he likes it. My father’s visit worked on him [Trump] like honey on a bee.”

As to what Trump was really after in his quest to reinvent himself as a statesman/politician, he may have revealed part of the answer when he told The Washington Post that the man who was egging him on was none other than the mentor he so looked up to, a man for whom motives were simple. Primal. There was always money. There was always a deal. There was always an angle, and a fix.

“You know who really wants me to do this?” Trump asked rhetorically. “Roy [Cohn].”

The more Trump expanded his business and saw the spotlight, the more he sought a bigger stage. In January 1987, Trump received a letter from Ambassador Dubinin that began, “It is a pleasure for me to relay some good news from Moscow.” The letter added that Intourist, the leading Soviet tourist agency, “had expressed interest in pursuing a joint venture to construct and manage a hotel in Moscow.” Vitaly Churkin, who later became ambassador to the U.N., helped Yuri Dubinin set up Trump’s trip.

On July 4, Trump flew to Moscow with Ivana and two assistants. He checked out various potential sites for a hotel, including several near Red Square.

He stayed in a suite in the National Hotel where Vladimir Lenin and his wife had stayed in 1917. According to Viktor Suvorov, an agent for the GRU, Soviet military intelligence, “Everything is free. There are good parties with nice girls. It could be a sauna and girls and who knows what else.”

All of which sounded great, except for one thing: Everything was subject to 24-hour surveillance by the KGB.

After the trip, The New York Times reported that while Trump was in Moscow, “he met with the Soviet leader, Mikhail S. Gorbachev. The ostensible subject of their meeting was the possible development of luxury hotels in the Soviet Union by Mr. Trump. But Mr. Trump’s calls for nuclear disarmament were also well-known to the Russians.”

But in fact, Trump’s meeting with Gorbachev never really took place. The report, apparently, was merely Trumpian self-promotion. Moreover, there are many unanswered questions about exactly what transpired during Trump’s visit. It is not clear whether Trump understood that Intourist was essentially a branch of the KGB whose job was to spy on high-profile tourists visiting Moscow. “In my time [Intourist] was KGB,” said Viktor Suvorov. “They gave permission for people to visit.”

Nor is it clear if Trump was aware that Intourist routinely sent lists of prospective visitors to the first and second directorates of the KGB based on their visa applications, and that he was almost certainly being bugged.

As to what activities the KGB may have captured in its surveillance, Oleg Kalugin, as the former head of counterterrorism for the KGB, is well versed in the use of video to produce kompromat (or compromising materials), particularly of a sexual nature. At the time, it was a widespread practice for the KGB to hire young women and deploy them as prostitutes to entrap visiting politicians and businessmen, and to use Intourist to monitor foreigners in the Soviet Union and to facilitate such “honey traps.”

“In your world, many times, you ask your young men to stand up and proudly serve their country,” Kalugin once told a reporter. “In Russia, sometimes we ask our women just to lie down.”

Which, according to Kalugin, is what probably happened during Trump’s 1987 trip to Moscow, during which he would have “had many young ladies at his disposal.”

To be clear, Kalugin did not claim to have seen such material or have evidence of its existence but was speaking as the former head of counterintelligence for the KGB, someone more than familiar with its tradecraft and practices. “I would not be surprised if the Russians have, and Trump knows about them, files on him during his trip to Russia and his involvement with meeting young ladies that were controlled [by Soviet intelligence],” he said.

On July 24, 1987, almost immediately after Trump’s return from Moscow, an article appeared in a highly unlikely venue, the Executive Intelligence Review, that strongly suggested something mysterious was going on between him and the Kremlin. “The Soviets are reportedly looking a lot more kindly on a possible presidential bid by Donald Trump, the New York builder who has amassed a fortune through real estate speculation and owns a controlling interest in the notorious, organized-crime linked Resorts International,” the article said. “Trump took an all-expenses-paid jaunt to the Soviet Union in July to discuss building the Russians some luxury hotels.”

Were the Soviets really supporting a Trump run for the presidency? Was Trump seriously considering it? Answers to the second question began to materialize less than two months after his return from Russia, when Trump turned to Roger Stone, a Nixon-era dirty trickster then with the firm of Black, Manafort & Stone, for political advice. Trump had met Stone and his colleague Paul Manafort through Roy Cohn. Although they worked in somewhat different spheres—Cohn was a hardball fixer, Stone a political strategist and lobbyist—to a large extent, they were cut from the same ethically challenged cloth.

Under Stone’s tutelage, on September 1, 1987, just seven weeks after his return from Moscow, Trump suddenly went full steam ahead promoting his newly acquired foreign policy expertise, by paying nearly $100,000 for full-page ads in The Boston Globe, The Washington Post, and The New York Times calling for the United States to stop spending money to defend Japan and the Persian Gulf, “an area of only marginal significance to the U.S. for its oil supplies, but one upon which Japan and others are almost totally dependent.”

The ads, which ran under the headline “There’s nothing wrong with America’s Foreign Defense Policy that a little backbone can’t cure,” marked Trump’s first foray into a foreign policy that was overtly pro-Russian in the sense that it called for the dismantling of the postwar Western alliance and was very much a precursor of the “America First” policies Trump promoted during his 2016 campaign.

“The world is laughing at America’s politicians as we protect ships we don’t own, carrying oil we don’t need, destined for allies who won’t help,” he wrote. “It’s time for us to end our vast deficits by making Japan and others who can afford it, pay. Our world protection is worth hundreds of billions of dollars to these countries and their stake in their protection is far greater than ours.”

Given the extraordinary success of the Western alliance as the underpinning of American foreign policy since World War II, one can only wonder who, if anyone, helped Trump come up with policies that were so favorable to the Soviets. Even more startling, an article published the next day in the Times suggested that Trump might enter the 1988 Republican presidential primaries against George H. W. Bush, then the incumbent vice president. “There is absolutely no plan [for Trump] to run for mayor, governor or United States senator,” said a Trump spokesman. “He will not comment about the presidency.”

That tease—a refusal to comment on a question that no one had asked—did not take place in a complete vacuum, however. Earlier that summer, a Republican activist named Mike Dunbar from Portsmouth, New Hampshire, had approached Trump with a proposal to speak before the Portsmouth Rotary Club, an obligatory stop for presidential candidates in the first presidential primary state. After proclaiming that Vice President George H. W. Bush, the odds-on favorite to be the GOP nominee, and Senator Bob Dole, another contender, were “duds,” Dunbar said that he raised money and collected 1,000 signatures to put Trump on the 1988 primary ballot.

But Bush had a commanding lead in the race for the Republican nomination, and Trump himself had another issue he needed to deal with. Trump had felt Ivana’s awkward English and heavy Czech accent would be liabilities on the campaign trail. It was not a happy relationship and in fact his marriage was an issue he wanted to resolve before making a serious presidential run. Nevertheless, Donald Trump’s presidential quest was under way.

Trump’s White House ambitions did not make an especially deep impression on American voters in the 1980s, but foreign agencies took notice. Several months after Trump’s visit to New Hampshire, Ivana returned to her homeland, where the Czech StB continued to keep a close eye on her. StB agents suggested Ivana was nervous throughout the trip because she believed U.S. embassy officials were following her at a time when she was supposed to be meeting with Czech security operatives. Twice, the American ambassador to Prague, Julian Martin Niemczyk, invited her to visit the embassy. But Ivana declined.

Meanwhile, the Czech secret police filed a classified report dated October 22, 1988, saying that “as a wife of D. TRUMP she receives constant attention ... and any mistake she would make could have immense consequences for him.”

In addition, the StB report made two noteworthy revelations. For the first time, it was clear that Trump had decided he would run for president. The question was timing. “Even though it [his presidential prospects] looks like a utopia,” the awkwardly translated report said, “D. TRUMP is confident he will succeed.” Only 42, the report added, Trump planned to run as an independent candidate in 1996, eight years hence.

Finally, the StB file made one more curious observation about Trump’s political future: It said he was being pressured to run for president. And exactly where was the pressure coming from? Could it have been kompromat from the honey trap in Moscow? Unfortunately, the answer was unclear.

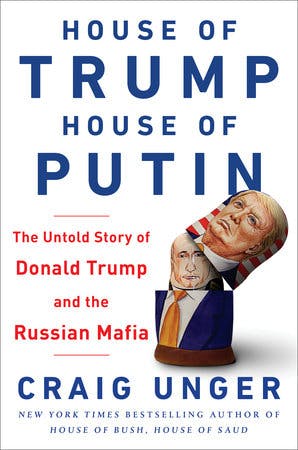

This article was adapted from House of Trump, House of Putin by Craig Unger, published this month by Dutton. Copyright © 2018 by the author.