America has federal laws about milk that leave little room for interpretation: The product must be produced in sanitary environments to prevent milk-borne disease. It also must be packaged in hermetically sealed containers, to prevent leaks and spoilage. But what is milk, precisely? That’s not as black and white.

Scott Gottlieb, the commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration, took a step toward answering that controversial question on Tuesday. Speaking at a policy summit in Washington, D.C., he suggested that no product that doesn’t come from a lactating animal should be allowed to call itself milk. “An almond doesn’t lactate, I must confess,” he said, drawing laughs from the audience.

For nearly two decades, farmers and dairy trade associations have been asking the FDA to ban terms like “soy milk,” “almond milk,” “hemp milk,” and “oat milk”—and if the agency won’t go that far, then to ban those products from the increasingly competitive dairy section. Those terms not only mislead consumers and harm the industry, they argue, but violate the FDA’s legal definition of milk as “the lacteal secretion, practically free from colostrum, obtained by the complete milking of one or more healthy cows.”

While previous FDA commissioners were sympathetic to this argument, none were willing to aid the dairy industry’s war against plant-based milks—until Gottlieb. He confirmed on Tuesday that the Trump administration is planning to redefine the labeling rules for milk to be more in line with the dairy industry’s wishes. “[The] FDA plans to solicit public comment on the issue soon before taking further steps,” Politico reported, adding that the process will likely take about a year.

The plant-based milks industry is ready to fight back. “If FDA were to ban the use of dairy terms on plant-based products, we would sue,” said Bruce Friedrich of the non-profit Good Food Institute. Several other groups are prepared to do likewise. At stake, they say, is not just the definition of milk, but the future of commercial free speech.

The feud between dairy producers and alternative milk manufacturers began on February 28, 1997, when the Soyfoods Association of North America asked the FDA to allow the term “soy milk.” The FDA said yes, and in 2000, the National Milk Producers Federation made its own request: That the agency “make clear to manufacturers of imitation dairy products that product names permitted by federal standards of identity, including dairy terms such as ‘milk,’ are to be used only on foods actually made from milk from animals like cows, goats, and sheep.” But the FDA refused to weigh in.

The battle spilled into American living rooms in 2012, when the California Milk Processor Board changed the tone of its iconic “Got Milk?” campaign. Ads that once focused on strong bones and milk mustaches were now about the terrifying prospect of plant-based milk. In one commercial, a mother attempts to comfort her son with a glass of soy milk after he awakens from a nightmare. She shakes the soy milk box so vigorously, she becomes demonic. The boy screams and runs right into a wall. “Real milk needs no shaking,” the narrator says. “Got Milk?”

The ad is meant to be funny, but the industry couldn’t be more serious about the issue. “You haven’t ‘got milk’ if it comes from a seed, nut, or bean,” said Jim Mulhern, the president of the National Milk Producers Federation, said in a statement advocating for FDA action. International Dairy Foods Association president Michael Dykes said that plant-based beverages “do not naturally provide the same level of nutrition to the people buying them as milk does.” Putting a “milk” label on those products “can mislead people into thinking these products are comparable replacements for milk,” he added, “when in fact most are nutritionally inferior.”

It’s true that plant-based milks are not as conventionally nutritious as cow’s milk. Compared to soy, almond, coconut, and rice products, dairy milk is “the most complete and balanced source of protein, fat and carbohydrates” according to a recent study in the Journal of Food Science and Technology described by Time. Per serving, cow’s milk has about 8 grams of protein, 9 grams of fat, and 11.5 grams of carbohydrates, the study said. The most comparable plant alternative is soy milk, which per serving has about 8 grams of protein, 4.5 grams of fat, and 4 grams of carbohydrates.

But nutrition is a complicated, often messy scientific field, and what’s “healthy” depends on individual needs and opinions. Soy milk, for instance, contains more fiber than cow’s milk, and reduces cholesterol instead of increases it. Does that mean it’s less nutritious than cow’s milk, but more healthy? Some pediatricians believe it’s not healthy for children to drink non-human milk; others believe it’s very healthy.

Advocates of alternative milks say these debates, while important, are not relevant to the definition of milk. “As the [FDA] Commissioner noted, the dictionary definition of the word ‘milk’ does include coming from nuts, and this is not a new concept,” the Plant Based Food Association said in an emailed statement. Indeed, Gottlieb on Tuesday acknowledged that “if you open up a dictionary, it talks about milk coming from a lactating animal or a nut.”

This is one of several reasons why non-dairy milk companies reject the idea that they’re misleading consumers. “People understand the difference between dairy milk and plant-based choices,” said Michael Neuwirth, a spokesperson for Silk, which sells a variety of nut-based beverages. “We communicate on our products in a way that avoids confusion between dairy and plant-based.” Some advocates argue that consumers would be misled if non-dairy companies stopped calling their products milk. “No one thinks that almond milk or soy milk comes from cows,” Friedrich of the Good Food Institute said. “There is no consumer confusion, but requiring any sort of change would certainly confuse consumers, who have been buying almond milk and soy milk for decades.”

Friedrich believes that the dairy industry’s accusations wouldn’t hold up before a judge. “Multiple courts have considered the issue of consumer confusion,” he said. “All of them have essentially laughed the concept out of the courtroom.” If customers aren’t being misled, they’re not being harmed.

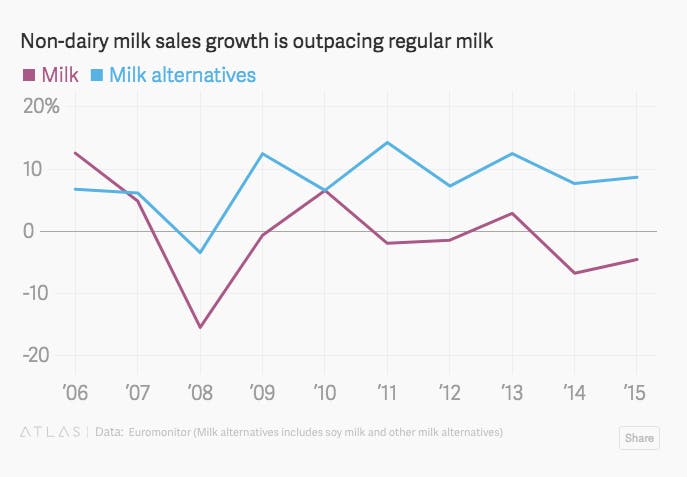

The dairy industry, however, has clearly been harmed by the rise of alternative milks. The New York Times reported last year that dairy milk sales fell from $15 billion in 2011 to $12 billion in 2016, partly because “people switched to other beverages, such as soft drinks, fruit juices, bottled water and soy and almond milk.” Plant-based milks “still represent a fraction of the beverage market,” the Times added, but “they are growing in popularity. According to Nielsen, sales of plant-based milks have surged to $1.4 billion from $900 million in 2012.”

The growth of alternative milks thus represent an existential threat to the dairy industry, which is already reeling from President Donald Trump’s trade war with China and Mexico. But Friedrich argues that the industry can’t control trends in consumer choice by changing the name on a label—nor should they, he said, because it violates companies’ First Amendment right to call their products what they want.

“The government is only allowed to restrict commercial speech if there is a substantial risk of consumer harm and their solution is narrowly tailored to solve the harm,” said Friedrich. “As we discussed in our rulemaking petition, there is no way that the act of censoring plant-based milk makers would be able to clear this clear constitutional bar.” Last year, Friedrich’s group filed a petition asking the FDA to explicitly allow plant-based producers to call their products milk, so long as they use qualifiers like “soy” and “almond.”

But Friedrich is optimistic about the alternative milk industry’s chances against dairy producers. The FDA’s Gottlieb is one of the more qualified members of the Trump administration, he said, with a “laudable record of combining an understanding of scientific nuance with common sense practicality.” But if Gottlieb ultimately sides with the dairy industry, then the question becomes: Got a lawyer?