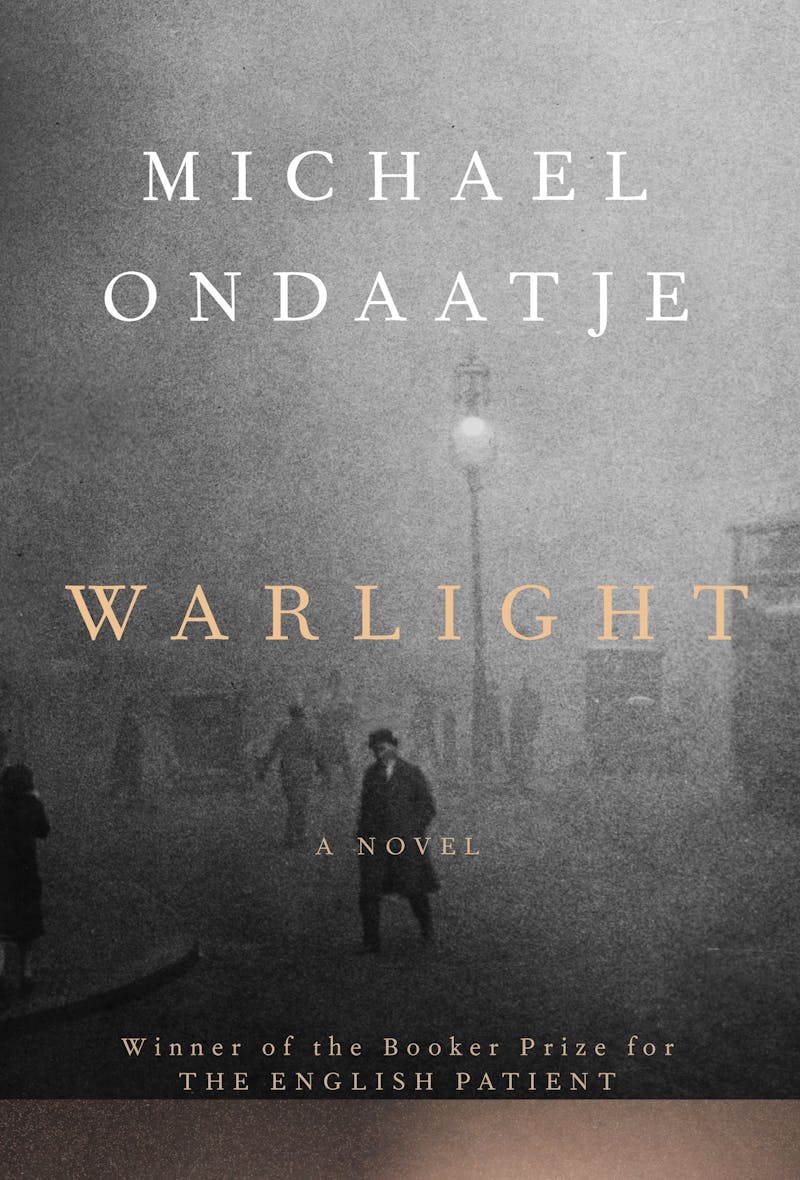

The cover of Michael Ondaatje’s new novel Warlight shows an archival photo of a 1930s London streetscape bathed in fog. The warm glow of a street lamp struggles to cut through the pea soup, but the details of the scene remain indefinite, blurry, faintly mysterious; the people’s faces shrouded in shadow; the sky grainy and gray on the old-fashioned film. It is at once ominous—anything, one feels, could happen in those alleys—and alluring, a magical space suffused with soft light; a lost landscape to sink into and explore. The novel’s plot is much the same: Set in London in 1945, a city still broken from the Blitz, Warlight is a lyrical journey into the past, illuminating, as its title implies, both the traumas and the possibilities of rebuilding a life after war.

It seems right to judge an Ondaatje novel by its cover: The characters in his books are voracious readers who delight in covers, plots, pictures, and epigraphs, the little handwritten notes and doodles in the margins. They read histories to understand their own lives. They read fantasies to escape into other worlds. They listen to each other’s stories to stitch together their community. In Ondaatje’s Booker Prize-winning The English Patient, the protagonist, Hana, writes her own story onto a blank page at the back of a book in the library, “in order to collect herself.” She nails together books from the library to fill in gaps in the staircase, literally climbing up on the spines of the authors who came before. Storytelling, Ondaatje insists, is our greatest invention, a subtle form of knowledge, an essential link to other people, an artistic tool with which to create ourselves anew.

Warlight, an entrancing and masterfully crafted story, is itself stuffed full of other stories. It begins with two teenagers, Nathaniel, the narrator, and his sister, Rachel, who are left in the care of a family friend nicknamed The Moth in post-war London. The Moth may or may not be a thief; their parents have disappeared on a secret mission abroad, perhaps connected with the war and its aftermath. The Moth invites his friends to the children’s house every evening, and together they make up a motley crew of misfits surviving at the edges of society. The first part of the book is appropriately titled “A Table Full of Strangers,” echoing the ragtag bunch of friends and refugees in Ondaatje’s last novel, The Cat’s Table.

Nathaniel rightly describes their house as “an amateur theatre company.” As new characters come briefly onstage, they bring with them entire other lives, backstories half-glimpsed through a quick introduction or an offhand comment. The Moth is a hotel manager and classical music lover who slips away at odd hours of the day and plays Schumann’s melancholic Mein Herz ist Schwer late into the night. The Moth’s closest friend, The Darter, an ex-boxer, is a smuggler and raconteur who takes Nathaniel under his wing. Arthur McCash, a small, shy lover of French literature, hints at being a spy during the war and implies that the children are in danger from their mother’s secret mission. A travel writer and geographer named Olive Lawrence leads Nathaniel and Rachel on a walk through a park in the evening, describing the faraway places she’s seen, unfolding “all these landscapes within her.” “Your own story,” she says, “is just one, and perhaps not the important one.” Then Olive disappears on her own journey, sending back only postcards.

No one in the novel is who they appear to be. Everyone wears a mask. The drama is driven by Nathaniel’s efforts, many years later, to peel off those masks, to uncover the real characters of the people who shaped him as he grew up, “that remarkable table full of strangers who had altered me.” In particular, he is trying to remember his mother. She abandons him in London in 1945 and then returns a year or so later to live with him in a small village in the countryside, only to die soon after in mysterious circumstances, leaving him alone again. The novel is meant to be Nathaniel’s memoir of that time, and “when you attempt a memoir,” he explains, “you need to be in an orphan state.”

Nathaniel works to piece together his mother’s life from the fragments she left behind. But her character remains as indistinct to him as the figures on Warlight’s cover. He keeps a photograph of her as a girl, but even that ostensibly objective evidence is inconclusive. In the snapshot, “her features are barely revealed,” her identity disclosed only by “her stance, some gesture in her limbs.” She is an “almost anonymous person,” Nathaniel says, “balanced awkwardly, holding on to her own safety. Already incognito.” So he fills in her hazy outline with his own experience, recreating her as an imagined character in a story based partly on himself, his memoir blurring into fiction—“I believed something in my mother must rhyme in me.”

Rhyming is Ondaatje’s literary forte. He began his writing life as a poet, and when he shifted into prose, he carried with him a deft touch with metaphor and an uncanny ability to find the little resonances, the rhymes, between the disparate lives of his characters. In Ondaatje’s best book, Divisadero, Anna, the novel’s narrator—herself an echo of Hana in The English Patient—writes that life is “like a villanelle,” a recursive poem held together by its repeated rhymes. We return to “events in our past,” Anna says, “the way the villanelle’s form refuses to move forward in linear development, circling instead at those familiar moments of emotion. Only the rereading counts… We live permanently in the recurrence of our own stories, whatever story we tell.” Crucially, when we tell our own stories, we recover lost connections with the people we have known. “There is the hidden presence of others in us,” Anna writes. “We contain them for the rest of our lives.”

Ondaatje’s characters clearly retain the impressions made by others, but they also tend to lose each other, often painfully. In Warlight, Nathaniel declares that when their parents left, he and his sister “began a new life,” and that he is “still uncertain whether the period that followed disfigured or energized” him. When his mother returns, she has been literally disfigured, her arms covered in scars, her movements wary, her conversation guarded, even around her son. Rachel, in turn, is permanently hurt by being left behind; her split with their mother is “irreconcilable,” and she effectively cuts off Nathaniel too when he chooses to live with their mother. When he returns to London long after, Nathaniel is unable to reconnect with Rachel, who is now working as an actress. He cannot reassemble the people who used to sit at his table full of strangers.

Nathaniel eventually gets a job working for British Intelligence as a historian reviewing after-action reports from the last days of World War II. When he breaks into secret files at work, he discovers that his mother was indeed something of a spy. She “operated on the periphery of war,” he explains, in “an unauthorized and still violent war that had continued after the armistice, a time when the rules and negotiations were still half lit and acts of war continued beyond public hearing.” Ondaatje is referring to the ongoing partisan combat in the years immediately after WWII, in 1946 or 1947, in places such as Greece and Yugoslavia. It was an extension of hostilities after the conflict was putatively over, a time of shifting alliances and betrayals, great power politics by England and others, a post-war war whose lines were less clear than the stark confrontation with Hitler that came before.

Nathaniel sees his job as a historian and narrator, “a generation later,” as “unearth[ing] whatever evidence might still remain of actions that history might consider untoward.” As he dives into the archives of the past, finding civilian casualties wrought by the Allies in a world of “continual war,” it comes to seem “no longer possible to see who held a correct moral position” amid the shadows of covert action. Hence the need to probe the archives for what really happened: In our cultural memory of the wars of the past, only the rereading counts.

Ondaatje’s literary career in many ways echoes Nathaniel’s task. Warlight, Divisadero, The English Patient, and Ondaatje’s Prix Médici-winning Anil’s Ghost all circle around war and the challenge of remembering and recovering from war. Together, they sketch a century of modern warfare, from World War I to the War on Terror. Divisadero, most representatively, follows a series of intersecting characters whose lives are broken repeatedly by World War I, World War II, Vietnam, the First Gulf War, and then the Second. In one scene, Anna imagines her long-lost sister listening to the bombing of Baghdad on the radio in 2003, feeling “as if coupled in another time, at an outbreak in the Hundred Years War.” In Anil’s Ghost, Ondaatje similarly writes of the civil war in Sri Lanka, “It was a Hundred Years’ War with modern weaponry, and backers on the sidelines in safe countries,” a quintessentially contemporary low-intensity war of terror, torture, insurgency, state violence, and mass civilian death.

There is thus an intensely present focus in Ondaatje’s poetic recreation of the past. By returning to similar events from a long century of conflict, he seeks to understand our own world of endless war. There is, of course, a danger in substituting broad sentiment for a careful critique of today’s unjust wars: The causes of the War on Terror and ongoing low-intensity civil wars are not the same as the causes of the Hundred Years War, and a poignant novel about post-traumatic recovery won’t get a real-life war refugee past the border patrol. But perhaps at a time when so much of warfare is difficult to see—special forces operations, cyberattacks, mass surveillance, and drone strikes—a novel can illuminate the human suffering of war by looking at it askance. If that is true, then Warlight is a novel for today’s wars: an invitation, indeed a demand, that we recognize our dependence on others and the profound responsibilities that brings.