When it comes to the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow, there are two kinds of monuments in America. There are memorials that seek to honor this country’s fitful march toward civil rights. Then there are the statues of generals and politicians—as well as the highways and schools that bear their name—who broke from the union to preserve slavery as a way of life. So much of this country’s racial history is marked by nothing more than a tree, an empty space—sites of forgotten trauma. On April 26, two new kinds of monuments will be unveiled in Montgomery, Alabama: The Legacy Museum and the Memorial for Peace and Justice, the latter being America’s first national monument to victims of lynching.

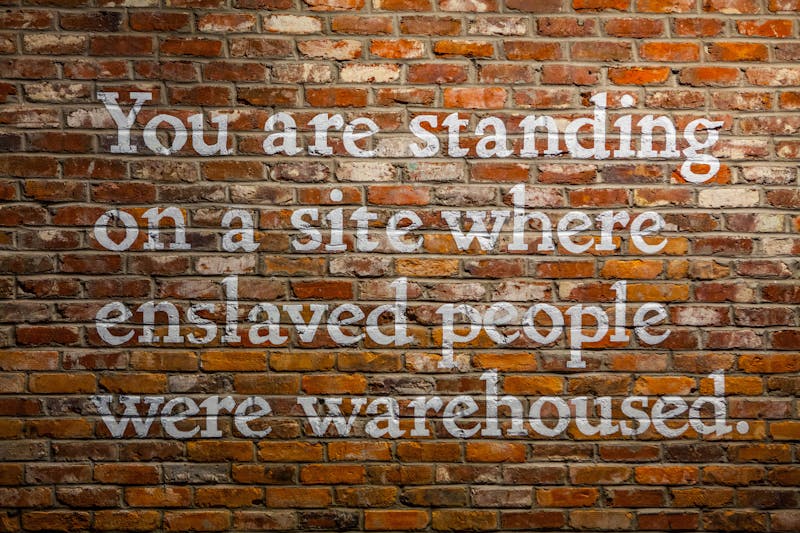

The museum sits on the site of a former warehouse where black slaves were imprisoned, between an infamous slave market and the dock that received blacks from the domestic slave trade. Relying on cutting-edge research and first-person accounts, it will leverage technology and a variety of media to showcase the tragedy of slavery, lynching, segregation, and more. The memorial, located on an elevated spot overlooking Montgomery, is a landmark structure: hundreds of columns suspended in air, like bodies dangling from branches, that represent the counties in America where lynchings took place. Together, the museum and memorial are unrivaled in the way they force the viewer to confront America’s violently racist past.

The monuments are the brainchild of Bryan Stevenson, founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, which unearthed approximately 4,400 incidents of lynching in nearly 800 counties, culminating in a 2015 report entitled “Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror.” The idea behind Stevenson’s project is that truth and reconciliation are not “simultaneous,” as he has said—they are “sequential.” And in his opinion, America has “done a terrible job of truth-telling in this country about our history of racial inequality,” instead skipping to the reconciliation part.

As a result, memorializing racial tragedy can lead to a double-forgetting of those afflicted—forgotten because the truth is bypassed in the rush to reconciliation, and forgotten yet again because the victims were terrorized in parts of the country that are routinely neglected. These monuments avoid the trap of double-forgetting by emphasizing the brutal truth about racial terrorism, and where it happened. They are a lesson for all such efforts going forward, including Tulsa’s Race Riot Centennial Commission, which seeks to “educate all citizens” about the 1921 massacre that decimated the black community there.

The Legacy Museum’s exhibits address everything from bondage to mass incarceration, and make declarative political statements about the America we live in today. It underscores “the destructive violence that shaped our nation” and reveals how that violence “traumatized people of color and compromised our commitment to the rule of law and equal justice.” It has taken cues from museums that have memorialized the tragic “histories of genocide, apartheid, and a host of human rights abuses in other countries,” including the Apartheid Museum in South Africa, the Genocide Memorial in Rwanda, and the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.

Americans may not be used to such unflattering comparisons. And there has been some discomfort with the Legacy Museum’s less-than-forgiving approach, which departs from the customary model of focusing on civil rights heroes, their accomplishments, and their embrace by white America. For instance, Dick Brewbaker, state senator representing Montgomery, critiqued the museum and memorial by asking, “Why is racially motivated violence worse than any other kind of violence?” With former Governor Robert Bentley’s removal of the Confederate flag from the capitol, Brewbaker believed that the “imbalance has been corrected.” He noted Montgomery’s museums dedicated to Rosa Parks and the Freedom Riders, suggesting that the city has enough tributes to the civil rights movements. But the Equal Justice Initiative believes that when those honorariums “are not accompanied by meaningful engagement with the difficult history of systematic violence perpetrated against black Americans, such celebrations risk painting an incomplete and distorted picture.”

Just a 15-minute walk from the museum lies the stunning Memorial for Peace and Justice, which compels the visitor to confront those 4,400 lynched bodies. The columns, made of Corten steel, surround visitors like a rust-colored forest. As they proceed further into the memorial, the columns rise higher to convey that these atrocities occurred in the public square. In the interior courtyard, they crowd around the visitors as if to remind the living of their judgment by the dead.

Identical columns outline the exterior of the memorial, but with the hope that they will only do so temporarily—the goal is that they will be claimed by and placed in the 800 counties where these lynchings occurred. The atrocities of these lynchings won’t be as easily forgotten when the columns sit in front of libraries, town halls, churches, and shopping districts. Instead of walking carefree on grounds once used to display and humiliate black bodies, residents of these towns will have to reckon with a truth obscured by our collective appetite for reconciliation.

I grew up nearly 725 miles away from Montgomery, in a part of the country that is arguably even more forgotten. Tulsa was once home to what was known as Black Wall Street, or Little Africa, which in the early 20th century boasted one of the country’s highest concentrations of black excellence. A beneficiary of Oklahoma’s oil boom, Black Wall Street featured a thriving business district and a professional class of lawyers, doctors, educators, and more.

On May 30, 1921, a simple accident between a black shoeshine boy and a white female elevator operator was intentionally misconstrued in a local paper as assault. White Tulsans took this as just cause to burn Black Wall Street to the ground. Over 5,000 black residents were arrested, approximately 300 were killed, and even more were injured. The fires consumed 1,256 homes, 191 commercial sites, some churches, and even schools, a hospital, and a library.

In Tulsa, reconciliation has outpaced reflections on truth. As a child, I never reflected on Ida B. Wells’s description of lynching: “the nineteenth century lynching mob cuts off ears, toes, and fingers, strips off flesh, and distributes portions of the body as souvenirs among the crowd.” Without second thought, I’d traipse around the grounds of what was Black Wall Street and saunter past the John Hope Franklin Reconciliation Park. I failed to see the devastation visited upon the community nearly a century ago. The memory of the hope that Little Africa once offered serves as the inspiration of commemoration efforts nearly a century later.

The Centennial Commission is considering the best ways to memorialize the devastation. Its efforts so far have focused on the progress to come—on hopes for reconciliation. But historical exercises that do not weight their reconciliation with painful truth often become pain suppressants. They do not relieve the deep pain that exists. At risk is a double-forgetting of what happened in 1921.

Forgetting is enabled by the language we use to describe the horror of that day. Calling it a riot minimizes the truth. It allowed insurers to escape the responsibility of paying benefits to the households and businesses set ablaze, leaving most of the financial burden of the community’s reconstruction to the victimized. The truth is: This was a massacre.

Today, the stain of this massacre and subsequent events have left black life fragile in Tulsa. The life expectancy of 74126, the zip code of much of black Tulsa, is 10.7 years less than that of 74137, a more affluent, predominantly white community.

Sixty-seven years old is the average life expectancy in 74126—if people can make it that long. Terence Crutcher barely reached 40 before a white police officer shot him, unarmed, just north of where Black Wall Street burned 98 years before. It’s an all too familiar story: white police officer shoots an unarmed black man without facing any prison time. As a community, Tulsa blew past the truth that historical context could bring. Instead, the city rushed to reconciliation in the usual places: churches, community centers. There were somber mayoral press conferences, and a gentle protest at the same Reconciliation Park.

But what if that same police officer who shot Crutcher had to see the names of the lynched on those steel columns as she drove by her local precinct to work every day? What if, staring Tulsans in the face, were the true stories of those afflicted by racism? That is the duty standing before the Centennial Commission: to anchor reconciliation in truth.

Such frank reflections on the truth might dissuade individuals like U.S. Senator James Lankford from serving on the commission. His proposed solution to racial strife is “Solution Sundays,” in which Americans are encouraged to invite someone of a different race to dinner. But instead of the commission’s “reconciliation committee,” perhaps what Tulsa needs is a “truth-first, then-reconciliation committee.” It need not look any further than Montgomery to understand that the way forward lies in the past.