More than 100 years ago, at the height of the last Gilded Age, Congress passed its first law prohibiting corporations from spending money to influence election campaigns. From the start, the wealthy chafed against this limit, and some sought to test it in court. Alcohol manufacturers—terrified of high taxes and Prohibition—might not have seemed the ideal candidates to take on this fight. But they were nonetheless the first to challenge the law, contributing cash to candidates in state and federal races and then arguing that any effort to keep money out of politics was no less than an unconstitutional limitation on free speech.

At that time, state and federal courts rejected these arguments out of hand. To the Michigan Supreme Court, for example, it was self-evident that a local brewery had no “right to participate” in elections. The company, wrote the chief justice in a 1914 decision, was created not to engage in politics, but “for the purpose of manufacturing beer.” In a different case involving the Brewers Association, a federal court ruled that corporations “are not citizens of the United States,” and that as far as the franchise went, they must “at all times be held subservient to the government and the citizenship of which it is composed.”

Yet the beermakers finally had their day in 2010, when the Supreme Court issued its ruling in Citizens United. In a reversal of last century’s common sense, the Court found that corporations did have free speech rights after all and that campaign finance laws placed an intolerable restriction on those rights. In the next presidential election, corporate spending soared. Companies gave over $70 million in disclosed contributions to super PACs and likely hundreds of millions more in “dark money” donations to political groups that do not have to make public the details of their financing. Donate to one of these organizations and, as one fund-raising pitch put it, “No politician, bureaucrat, no radical environmentalist will ever know.”

For many critics, this sluice of cash was not the only troubling feature of Citizens United. It reflected a vision of society in which successful businesses and their leaders, as the winners in the marketplace, are seen as having earned a form of authority. To restrict their capacity to influence public opinion would be to impose a limit on the most talented and deserving people and unfairly favor the masses. The shift toward this view grew directly out of the rightward surge of the late twentieth century, a period of intense activism on the part of conservatives and business leaders. The case that led to the ruling had been brought by a libertarian political organization that sought to finance a film attacking Hillary Clinton, while the decision itself came down from a fiercely partisan Court, dominated by conservative jurists.

Yet the decision was no short-lived, ideologically driven detour. In his new book, We the Corporations: How American Businesses Won Their Civil Rights, Adam Winkler, a law professor at UCLA, makes the case that Citizens United was the logical result of 200 years of jurisprudence that clearly establishes constitutional rights for corporations. This body of law is itself the result of a lengthy campaign by the business class to win a set of rights for its companies and thus to expand its own political reach. There has been, Winkler suggests, a literal “civil rights” movement for corporations, led by people who have the financial means and social connections to hire skilled lawyers, the acumen to choose promising test cases, and the patience to wait for Supreme Court decisions. In this way, Winkler’s book is more than a legal history: It is a history of the forces that make the law.

Scholars, activists, and writers on the left have long treated the corporation as (to quote Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis) a “Frankenstein monster.” By patching together scraps of wealth to form an uncanny whole, a corporation becomes an immortal being that can outlive any individual investor, even when it bears a founder’s name. Some, like Brandeis, have seen in the rise of such companies a threat to older dreams of individual freedom. For him, as for many throughout the nineteenth century, owning your own land or small company was a prerequisite of genuine political and cultural independence, while waged work was associated with being reliant ultimately on the whims of an employer. Corporations fundamentally transformed what it meant to own property, by bringing together, the economists Adolf Berle and Gardiner Means wrote in the 1930s, the wealth of “innumerable individuals” and surrendering it to a “unified direction.” The leaders of these new entities were virtual “princes of industry, whose position in the community has yet to be defined.”

Their growing power stoked a long-standing anxiety about the ability of concentrated wealth to shape politics. Beyond this, many feared that the corporation—the ultimate embodiment of the power of technology and capital—would come to dominate and drive the human society that created it. For C. Wright Mills and other skeptics in the 1950s, the individuality of employees disappeared within the gray-suited structure of the corporation. Later, the libertarian ideologies of Silicon Valley celebrated the anarchic entrepreneur as a force disrupting stable corporate hierarchies. More dramatically, Canadian law professor Joel Bakan has made an analogy between corporations and psychopaths, arguing that corporations act as pathological, fantastical “individuals” shorn of any moral compunction, driven by the absolute imperative of profit alone.

Winkler’s approach is different from the outset. He does not see corporate behemoths as a deviation from the ideal of a land of small entrepreneurs. Nor does he see the corporate form—the structure that allows a business entity to have a degree of independence from those individuals who found it—as inherently menacing. The British colonies, he points out, were settled by private organizations such as the Massachusetts Bay Company and the Virginia Company, entities that had stockholders and were governed by charters—essentially, by corporations. “Democracy and constitutionalism,” as he puts it, “were intimately tied up with the corporation from the very beginning.”

The powers of corporations were very different in those early days. In the first decades of the republic, people seeking the benefits of incorporation would obtain a charter from the state for a particular purpose. The legislature had the capacity to revoke or change the charter, as the needs of the community shifted. It was not even clear that corporations had the independent ability to conduct lawsuits; this was established only early in the nineteenth century, when the First Bank of the United States won the ability to sue in federal court, a decision Winkler describes as the first step in the winning of civil rights for corporations.

Then, in 1819, the state of New Hampshire got embroiled in a dispute among the board of trustees of Dartmouth College and sought to revise the school’s corporate charter. The original trustees sued, saying that the state had no right to interfere with private contracts. They made the excellent decision to hire Daniel Webster, an alumnus of Dartmouth who would become one of the leaders of the Whig Party as well as the foremost constitutional lawyer of his generation, to argue their case before the Supreme Court. The Court ruled that corporations were private entities with their own legal rights, and that the legislature could not simply change their charters. Previously, the legislature was supposed to be the ultimate authority. But in Dartmouth College, the private corporation was found to possess an autonomy upon which the government had no right to infringe.

The concept of corporate rights broadened still further in the years after the Civil War. In the antebellum era, most businesses were small-scale enterprises that produced and sold to local markets. This was beginning to change even before the war, and in the second half of the nineteenth century, new companies—led by the railroads and followed by the oil and manufacturing giants—that did business on a national level began to emerge. They employed thousands of workers, rather than dozens; they had offices in multiple cities and regions; the capital they amassed dwarfed anything in the earlier period. Such massive entities needed a legal structure that went beyond the individual partnership, and their leaders embraced the corporate form, for the autonomy and stability it offered as well as the protections for individual investors.

Winkler suggests that the corporate turn also afforded the rich a new way to push for more rights. Canny businessmen in the late nineteenth century laid claim to the 14th Amendment to argue that its purpose was not so much to preserve the citizenship rights of the formerly enslaved people of the South, but to articulate new rights for corporations—in particular, their rights to be free of taxes and regulations. When the railroads confronted new taxes from state governments, they engaged in what Winkler describes as “civil disobedience”: They refused to pay the taxes, made public arguments in the press about their illegitimacy, and ultimately sought out lawsuits as test cases.

In a case before the Supreme Court, Roscoe Conkling, a former Republican politician turned railroad lawyer, claimed to have documentary evidence showing that the language of the 14th Amendment had been chosen specifically in order to include corporations, rejecting the term “citizen” in favor of “person” so that the amendment would apply to corporate persons. Conkling seemed a credible witness: He had served on the Joint Committee on Reconstruction that had drafted the 14th Amendment (indeed, by 1882 he was its sole surviving member), and he pointed to a never-before-published record of the deliberations of the committee to make his case. While the document itself was legitimate, a closer reading by later historians found that it simply didn’t say what Conkling claimed. The committee had never made the changes he insisted it had and certainly had not done so in order to extend the amendment to corporations.

But even as the Court expanded the rights of corporations, Winkler suggests that it did not take the position that they were simply “people” who had to be afforded the exact rights due any individual citizen. On the contrary, the justices who took the most expansive view of corporate rights did so primarily because they saw corporations as collections of individuals who still retained all their own constitutional rights and who had the right to exercise them, even through the association of the corporation. The precise arguments aside, the willingness of business to bring cases to the Supreme Court enabled corporations in the early twentieth century to eke out a set of rights under the Fourth and Fifth Amendments—the right not to be searched without warrant and the right to due process (although Winkler points out that these were more limited than those afforded to individuals).

In a sense, corporations had been able to lay claim to many of the freedoms and protections afforded by the Constitution, while avoiding the myriad limitations of being an actual human person—after all, a corporation can’t be thrown in jail for breaking the law.

Throughout the twentieth century, corporations continued to make gains in the courts. Some of the rulings that anticipated Citizens United are surprising: A corporation was first found to possess First Amendment rights in the 1930s, in a case that pitted Louisiana Governor Huey Long against the major urban daily newspapers in his state. Long had attempted to impose an advertising tax on large dailies in an act of political retaliation against them, since many had published criticisms of him. The Court ruled that such a tax on the corporation would limit the “circulation of information” which the First Amendment sought to protect.

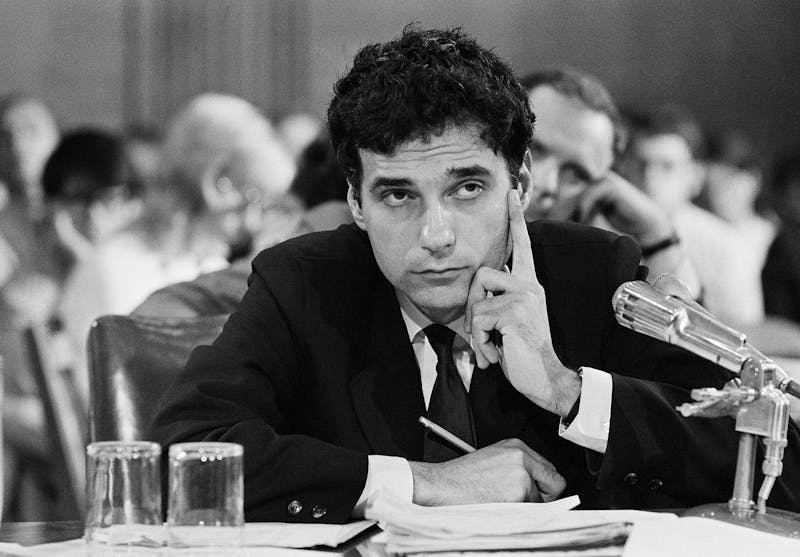

Corporations gained still more ground in the 1970s, when Ralph Nader’s Public Citizen Litigation Group challenged a Virginia law that prevented pharmacists from advertising the price of the drugs they sold. Although pharmacies could choose how much to charge for drugs, at that time the only way consumers could find out the price was by visiting or calling the pharmacy to ask. Placing limits on the speech of companies in this way, Nader’s lawyer argued, abridged the “rights of listeners”—in this case the consumer, who could not compare prices while shopping for medications. The Court went 7–1 in his favor, with William Rehnquist the only dissenter, and The New York Times described the decision as a victory for consumers’ rights.

But only a few years later, Nader’s victory would have unintended consequences. In 1977, the Court heard First National Bank of Boston v. Bellotti, in which the First National Bank of Boston and several other corporations claimed their right to fund a campaign against a ballot referendum in Massachusetts. The Court used the reasoning from the pharmacy case to argue that the State of Massachusetts could not restrict the bank’s spending and the speech it financed, because people had the right to hear what the bank might say: “It is the type of speech indispensable to decision-making in a democracy, and this is no less true because the speech comes from a corporation rather than an individual.” That decision was authored by Lewis Powell, who had famously written a secret memo to the Chamber of Commerce prior to his confirmation to the Court, urging business to take a strong stance against a rising “attack on free enterprise,” and so helping to spark a new era of conservative activism.

In the decades that followed, businesses and the wealthy would begin to organize with great fervor, responding to the challenges of the labor movement and the New Left in the 1970s, as well as to the worldwide economic decline of that time, with an offensive intended to roll back the power of unions, taxes, and regulations. This movement was not ideologically or strategically monolithic—it ran the gamut from expanded lobbying in Washington, D.C., by particular corporations, to the creation of new business organizations, such as the Business Roundtable, which aimed to provide a way for the CEOs of Fortune 500 companies to communicate their views to elected officials, to the spread of anti-union consulting firms. At once pragmatically, politically, and ideologically ambitious, the mobilization ranged from groups such as the American Legislative Exchange Council, pressing for business-friendly laws at the state level, to intellectual organizations and think tanks like the Heritage Foundation and the Cato Institute, which sought to rise above legislative jockeying and carve out a haven for conservative political ideas over the long term. Taken together, all this amounted to a tremendous intellectual and political effort to shift the political culture toward support for the interests of the very wealthy.

Citizens United itself emerged directly out of this re-energized conservative movement. The case is named for a right-wing group led by David Bossie, who would serve as Donald Trump’s deputy campaign manager in 2016. The group used corporate donations to finance a film bashing Hillary Clinton, titled Hillary: The Movie. Because of this funding, the Federal Elections Commission barred the distribution of the movie during the run-up to the 2008 election. One of the lawyers who worked with Bossie to bring the case to the Supreme Court was a libertarian activist who had been bringing cases for two decades challenging government regulation of money in politics. (He had once argued on behalf of a student who took on a college’s $100 spending limit in races for student government.) Another lawyer on the case had been a member of Bush’s legal team in Bush v. Gore in 2000—one of a number of elite, expensive lawyers who have been unusually successful bringing cases to the Supreme Court.

When the decision arrived, it echoed the rhetoric of the 1970s ballot referendum case, suggesting that political speech was “indispensable,” and that this was the case even when it came from “a corporation rather than an individual.” The Court argued that the government could not distinguish between different speakers, allowing speech by some and not others. The opinion resonated with the old idea that corporations were simply “associations” of individuals who possessed the right of free speech; their rights did not disappear simply because they were acting through a corporation. In short, Winkler writes, the decision was “the culmination of a 200-year struggle for constitutional rights for corporations,” not the “ungrounded invention” of a corporate-leaning Court.

In his argument that the recent legal victories for corporate rights have their roots deep in the past, Winkler joins historians such as Jefferson Cowie and N.D.B. Connolly, who have made the case that the rightward shift of American politics over the past few decades must not be seen as an anomaly. The conservative surge, as these scholars have argued, builds on long legacies of racism and inequality, and taps into an unquestioned faith in the virtues of individualism and private property and the genius of business executives. The recent ascendancy of the right takes elements that were always present and twists them in new ways. So, too, it seems, does the growing power of the corporation.

What does one do with a politics so deeply rooted? Winkler’s greatest strength as a writer is his capacity to convey detailed legal arguments in surprisingly pleasurable prose—no small accomplishment. But at some points, as though carried away by the sheer fun of legal argument, he seems to suggest that the best way to counter the expansion of corporate rights would simply be to take corporations at their word and treat them as people. That would not mean saying they can do as they please. The implication is that this new argument might lead the courts to see corporations as “legal persons but not necessarily the same as human beings,” and thus that they might be “afforded fewer and more circumscribed constitutional rights.” This, in turn, potentially could give the courts greater latitude to limit their political spending.

This emphasis runs counter to the rest of the book, which is otherwise so good at making the argument that the legal rights that are associated with the corporate form reflect something about social power. Winkler brings out just how difficult it is to get a case to the Supreme Court in the first place, the immense legal skill and resources that are necessary to accomplish this, and the ways that the entire process is most responsive to those people who have the time and money to command legal resources and marshal them toward winning constitutional decisions. Throughout the book, the reader is reminded that the law is neither steady nor fixed, but that it is created over time. What really matters—more than the specific doctrine of “corporate personhood”—is the people who stand behind the corporation, who have waged a long campaign to use the legal form to augment their political power and their economic might.

The Supreme Court handed down Citizens United, after all, in the wake of a mobilization of the American elite that has transformed public institutions and private life alike, reshaping the daily lived experience of workers, the policy ideas debated in think tanks, the legal education of justices, and everyday economic common sense. The spending of wealthy individuals such as the Koch brothers (whose power to make political contributions as individuals was hardly affected by the Citizens United ruling on corporations, as journalist Doug Henwood has noted in his newsletter, Left Business Observer) helped to make this change happen. So did the attempts of corporate management to proselytize to their own workers by, for instance, requiring workers to attend campaign rallies or forcefully communicating their political ideas in internal letters and memos—something for which they did not need additional legal permission (although Citizens United actually expanded their rights here as well).

It is unlikely, for all the reasons Winkler amply illustrates, that the courts will be the front lines of any challenge to the political power of the rich. As in the other civil rights movements of the twentieth century—most of which, it should be noted, have required that people take personal risks much greater than those taken by the corporate lawyers Winkler chronicles—this must involve changing the broader sensibilities of the nation through acts of confrontation large and small alike. Only then will the idea that people with more access to money should be able easily to dominate political life come to seem the absurdity and the affront that it truly is.