Donald Trump owes his presidency to the Electoral College more than any other factor, even Russian interference. This constitutional quirk also gives a hint of irony to an unusual bill passed earlier this week by Maryland’s Democratic-controlled State Senate.

The senators voted 28-17 on Monday, largely along party lines, to require presidential candidates to file copies of their tax returns with the state board of elections two months ahead of Election Day, so the filings can be made public. Failure to comply would result in the candidate’s removal from the state ballot that November.

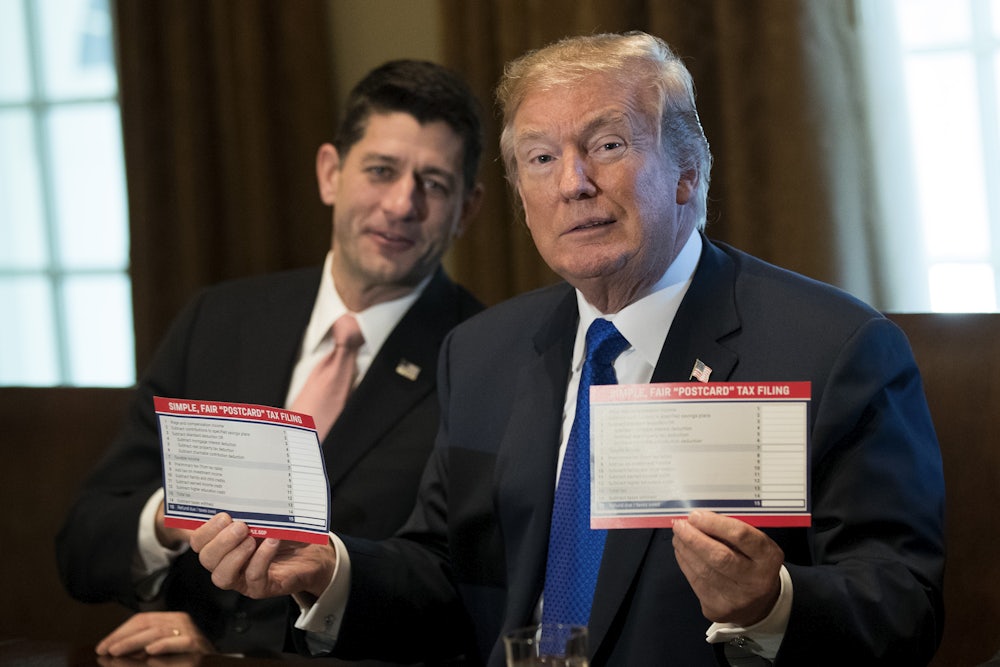

The bill’s target is clear: Trump, who broke a forty-year precedent by refusing to release his tax returns during his campaign. Now that he’s in the White House, the most reliable accounting of his wealth and debts is something of a state secret: the Internal Revenue Service keeps his returns (and those of other presidents) in a locked and guarded room that even the agency’s commissioner can’t access alone. States like Maryland are now working to fill that transparency void—and may be on solid constitutional footing to do so.

Rick Hasen, a U.C. Irvine law professor who specializes in elections, explored the possibility in a March 2017 article for Politico. At the time, he noted that almost half of the state legislatures were considering some kind of measure that would compel future presidential candidates to disclose their tax returns. The optimal path for this reform is through each state’s power to determine how it selects its presidential electors.

Today, the states invariably leave the choice to the voters. But the earliest American presidential elections saw a variety of methods ranging from popular vote to selection by state legislators. There’s no formal barrier that prevents a return to the old ways, either. “In other words, if the California or Texas state legislature wanted to directly choose the state’s presidential electors in 2020, the state could do so,” Hasen noted.

Since the states can tinker with the method of choosing electors, he explained, the argument follows that they could impose other barriers like the mandatory release of tax returns:

The logic then goes like this: If a state legislature can take back from the voters the right to vote at all for president, it may be able to use ballot-access laws to limit the candidate choices presented to voters. And doing so would not impinge on the Qualifications Clause in Article II because Congress ultimately counts the Electoral College votes and can police that Clause. If a state legislature, for example, chose electors supporting a candidate under the age of 35, the U.S. House of Representatives, which counts the Electoral College votes, could disregard those votes after deeming the underage candidate unqualified.

Hasen acknowledges that the tax-return maneuver is more of a “gambit” than a surefire strategy. “The Supreme Court might, if faced with the issue, hold that state legislators cannot require tax returns of presidential candidates even given state legislatures’ much greater power over presidential elections,” he wrote. He also warned that Republican legislators would almost certainly retaliate in state legislatures that they controlled.

Existing legal precedents regarding states’ power (or lack thereof) to restrict federal candidates pertain mainly to congressional candidates rather than presidential aspirants. The most famous episode involved Adam Clayton Powell Jr., the legendary New York City congressman who represented Harlem during the civil rights era. House members who grew weary of scandalous reports turned on him after his 1966 re-election and voted to exclude him from the legislative body. After three years of legal battles, the Supreme Court sided with the congressman in Powell v. McCormack.

Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote for the court’s majority that “in judging the qualifications of its members, Congress is limited to the standing qualifications prescribed in the Constitution.” Since Powell met those qualifications, “the House was without power to exclude him from its membership,” he concluded.

Another qualifications issue surfaced in 1992 when Arkansas voters approved an amendment to the state’s constitution to impose term limits throughout the state government. It also barred candidates seeking a fourth term in the U.S. House of Representatives or a third term in the U.S. Senate from having their names printed on election ballots for those offices.

That provision drew a legal challenge from a group of Arkansas voters, who argued that it went beyond what the Constitution authorized. The Supreme Court agreed, striking down the amendment’s restrictions on federal officeholders. Once again, the justices took an exclusive view of the Constitution’s qualifications.

“Allowing individual states to adopt their own qualifications for congressional service would be inconsistent with the Framers’ vision of a uniform national legislature representing the people of the United States,” Justice John Paul Stevens wrote for the majority in U.S. Term Limits Inc. v. Thornton. “If the qualifications set forth in the text of the Constitution are to be changed, that text must be amended.”

It’s possible the Supreme Court could rely on these precedents to strike down laws like the one working its way through the Maryland legislature. But the justices would have plenty of reasons to distinguish those rulings from today’s situation. While the Constitution might command uniformity in the national legislature, experience from the founding era shows that states enjoy wide latitude when choosing their electors for the chief executive. Public disclosure of one’s tax returns is also a much lower barrier for candidates to overcome than term limits or expulsion.

Other legal experts are also confident in the soundness of the tax-return maneuver. Laurence Tribe, a Harvard University law professor and frequent critic of the Trump administration, described Maryland’s bill as a “neutral, even-handed way” to allow voters to assess the “financial and ethical history” of would-be candidates. He also viewed its constitutional footing as more secure.

“It’s not an interference with any federal prerogative, nor does it filter out in advance any set of presidential candidates who meet the Constitution’s age, residence, and other qualifications,” Tribe said.

Before it faces a legal challenge, though, the bill has to become law. It now heads to the state House of Delegates, which is also controlled by Democrats, but would then need the signature of Governor Larry Hogan—a Republican who has yet to weigh in on the bill. If he were to veto the bill, Democrats could override it with a three-fifths vote in both the House and Senate. In the latter chamber, that means 29 votes: one shy of the number of senators who backed the bill this week.