Off the coast of Louisiana, in an 8,000-square-mile swath of ocean, the marine life is suffocating to death. Nutrient pollution, flowing from the Mississippi River into the Gulf of Mexico, is birthing huge clumps of algae that are sucking oxygen from the water. Without oxygen, fish are struggling to respirate, and fleeing the scene en masse. Plants and worms, being unable to flee, are wasting away. This so-called “dead zone” in the Gulf has been appearing every spring and lasting until the winter since monitoring began in 1985, but this year it grew to the size of New Jersey—the largest dead zone ever recorded in the world. Next year it will probably be bigger.

If you missed this news, that’s probably because this year’s news read like the script of a cli-fi drama. The U.S. had a record-breaking hurricane season, which begat yet more environmental destruction: Hurricane Harvey caused a toxic Superfund site overflow, excess carcinogenic air pollution, and a chemical plant explosion in Texas. Hurricane Irma caused millions of gallons of sewage to overflow all over the state of Florida. Hurricane Maria created a drinking water crisis in Puerto Rico (and may have killed more than a 1,000 people). California, meanwhile, is still dealing with the deadliest and most destructive wildfire season on record, also with environmental after-effects; in the Bay Area, toxic ash laden with heavy metals infiltrated the soil and made air unbreathable.

These catastrophes deservedly got wall-to-wall coverage on cable news, and front-page treatment in major newspapers. But in focusing on one kind of environmental disaster—extreme weather—many outlets overlooked another kind that’s destructive in its own right. About that dead zone in the Gulf, University of Michigan professor Don Scavia said, “Meat production is directly causing it.” This year, the meat industry has also been blamed for contaminating drinking water across the Midwest, destroying native species’ habitats, and increasingly for its role in causing global warming.

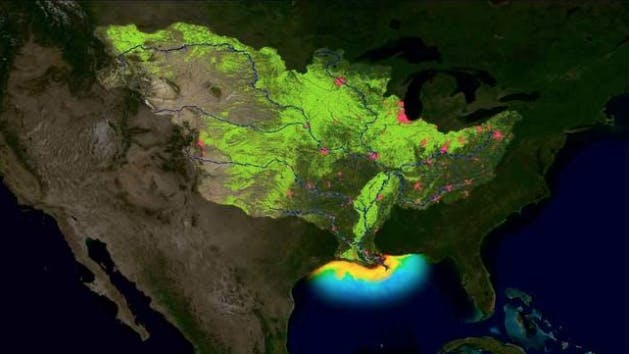

The meat industry’s main problem is its reliance on corn to feed animals. In 2016, corn crops caused most of the 1.15 million metric tons of nutrient pollution—excess nitrogen and phosphorus, mostly from fertilizer runoff—that was released into the Gulf. Thirty-six percent of those corn crops are used to feed chicken, cows, and pigs, most of which are eventually eaten by humans. As meat production increases, corn demand rises, producing more nutrient pollution and a bigger dead zone. The dead zone is bad for obvious reasons—as a concerned citizen once told Scavia, “8,000 square miles of no oxygen has got to be a bad thing”—but it also has consequences for humans, as it could decimate the Gulf shrimp industry.

Nutrient pollution has caused drinking water problems, too. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, “more than 100,000 miles of rivers and streams, close to 2.5 million acres of lakes, reservoirs and ponds, and more than 800 square miles of bays and estuaries in the United States have poor water quality because of fertilizer pollution.” Because of this, and how much meat contributes to nutrient pollution, the environmental group Mighty Earth released an investigation in August deeming the U.S. meat industry the largest source of water contamination throughout the Midwest. The pollution is “linked to cancer, birth defects, thyroid problems, as well as a serious condition called Blue Baby Syndrome, which lowers the amount of oxygen in infants’ blood,” the group claimed.

Mighty Earth also blames the meat industry for the destruction of American grasslands and prairies to make way for more cropland: One third of all land in America is used either to provide pasture for animals that will be eaten, or to grow feed for them. This practice “destroys the remaining habitat of native species like monarch butterflies, bees, pheasants, and prairie dogs, whose habitat has already been shrunk by 150 years of prairie clearance to serve agriculture,” the group says. Grassland and prairies are natural buffers, protecting waterways from pollution; the destruction of these habitats increases fertilizer runoff. “From feed to slaughter, our analysis found the meat industry to be the driving force behind some of the most urgent environmental crises facing our country,” the report read.

And then there’s the climate impact of meat. This year saw more warnings that meaningfully reducing global warming will require reducing emissions from animal agriculture, which make up 14 to 18 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions—more than the entire global transportation sector. Those emissions largely come from deforestation (since trees absorb carbon dioxide) and methane-rich cow farts; this year, NASA scientists revealed that the methane released by cow flatulence is contributing far more to climate change than previously believed. Two controversial peer-reviewed studies this year also showed how humans could meet international climate targets by changing their diets to replace meat with beans or bugs. (Diet changes could also prevent dead zones too, as U.S. fertilizer use would be cut in half if Americans switched to a mostly meatless, fish-heavy Mediterranean diet, according to one peer-reviewed study.)

These meat-related environmental issues aren’t likely to be addressed by the Trump administration. Trump, for one, doesn’t care about the climate impact of anything; he’s made that clear with his appointment of climate deniers to run almost every major agency that exists. His secretary of agriculture, former Georgia Governor Sonny Perdue, hails from the country’s top chicken-producing state and has “received hundreds of thousands of dollars in campaign contributions from agribusiness,” according to Bloomberg. In April, Perdue threw out an Obama-era rule intended to protect small farmers from bigger meat companies, signaling to farmer advocacy groups that the administration bends to the will of so-called “Big Meat.” Next year, Congress is supposed to introduce the quinquennial Farm Bill, which among many other things can fund programs to help nutrient management. But if it’s anything like Trump’s budget proposal for the USDA, it will “streamline” conservation programs intended to do just that.

But citizens need not depend on the Trump administration to address some of these problems. Big meat companies can and should be lobbied directly. Seventy-seven percent of consumers say sustainability factors into their food purchasing decisions. If people think a particular brand is destroying the planet, they are less likely to buy it. That’s why big meat companies like Tyson Foods are constantly promoting their sustainability initiatives and countering public criticism. Tyson’s senior director of public relations Gary Mickelson told Modern Farmer that Mighty Earth’s report was unfair because the company doesn’t farm the corn or even raise the cows. “It’s important for us to point out the supply chain, and say, hey, we’re not involved in the crop production business, and frankly, we own very few farms,” Mickelson said.

But the big companies like Tyson do dictate the way the entire crop market operates. If they demand that their suppliers have more sustainable fertilizer practices, those farms will be forced to change. As Modern Farmer points out, “these companies are the fulcrum in the entire system—the only entity with enough sway to truly change the way the whole system works.” In a year when it appears hopeless to convince the government to do anything to improve the environment, some targeted activism against the meat industry might actually make a difference. Making a conscious choice to eat less meat could help, too.