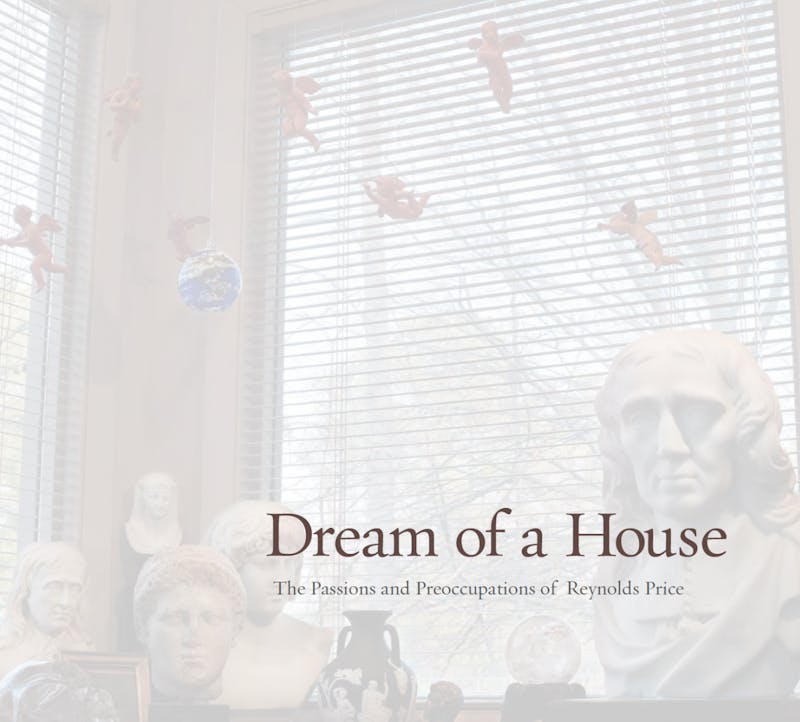

A few weeks after Reynolds Price died in January of 2011, his friend Alex Harris took a camera into the writer’s house, where Price had lived since 1965. Harris, who has worked for decades as a photojournalist, began taking pictures of the home—the entire thing, from floor to ceiling, as if it were a crime scene. He looked out Price’s windows, up his stairs, and across his rooms, capturing photographs of the Kartikeya statue on the table and the bobblehead Jesus in the window sill, compact discs and wood carvings, crucifixes and coins, doodles and children’s drawings, the fossils by the fireplace, framed pin ups and leaning polaroids, paper angels hanging from strings, an empty wheelchair in the office. “Alone in Reynolds’s rooms,” Harris remembered, “I knew my job was to focus.”

Harris returned over and over again, for weeks, until he had taken more than seven hundred pictures. “I worked at first like a photographic archivist,” he says, “with a responsibility to preserve and record Reynolds’s home as precisely and accurately as I could.” Some of these photographs were included in an exhibition in the Rubenstein Photography Gallery at Duke University, but more than sixty of them can be found in Dream of a House: The Passions and Preoccupations of Reynolds Price.

Price, who taught at Duke for decades, was born in Macon, North Carolina, less than a hundred miles away from the house that Harris photographed. He came of age in a smattering of small towns, and except for the years he spent abroad on a Rhodes Scholarship, he lived his adult life almost entirely in Durham. He called his deckhouse, a post and beam number with a little brick and some wood paneling, a “socket into the earth and into the sky,” and the rootedness it gave him was integral to his work. He liked to write for six hours a day, six days a week, for eight months of the year, preferably at his own desk in the deckhouse, producing 350 or so words every day. Slowly and steadily, he published 41 books: memoirs, novels, plays, translations, and volumes of poetry. He became one of the most influential and critically acclaimed writers of the twentieth century, accomplishing almost all of his work while looking out the same window.

Harris’s book is a beautiful tour of the space in which Price wrote. Eschewing captions or annotations, Harris and his wife, Margaret Sartor, declined to identify the faces of those pictured in the snapshot along Price’s walls, or to annotate all the works of art that appear in their book, instead setting the pictures against excerpts from Price’s poetry and prose. The writer’s words illuminate the photographs, briefly and brightly like lit matches that fade when the page turns. The pairings reveal more about Price and his work than any inventory could; they are followed by brief essays from Santor and Harris describing their friend and the experience of trying to narrate his work through photographs. Dream of a House is more like a visual biography than an attempt at making a museum between two covers, and Price’s estate seems to have chosen actively against the common model of leaving the house as it was when the writer lived there. Not long after Alex Harris took his photographs, the house was sold to one of Price’s former students.

Writer’s houses are common destinations for the literary pilgrim. Birthplaces, homesteads, dorm rooms, prison cells: almost any dwelling will do. Emily Dickinson’s house in Amherst is open to visitors, as is the Brontë Parsonage in Haworth. Cities up and down the East Coast preserve and promote properties affiliated with Edgar Allan Poe. You can smell Anne Spencer’s perennials in Lynchburg, pet descendants of Hemingway’s polydactyl cat on Key West, or find a feather from honorary surrogates of Flannery O’Connor’s peacocks in Milledgeville.

For some, these houses are destinations because of the connections between a literary work and where it was written; for others, they are occasions for learning more about an author by seeing where she spent her early, married, mad, or dying years. These spaces also provide opportunities for fellowship in what is often the solitary activity of reading, a place for admirers to meet and share their enthusiasm. Anne Trubek wrote a “Skeptic’s Guide” to writers’ homes, while A.N. Devers founded an entire website to catalog them.

That website won’t be updated to include Reynolds Price. Instead Dream of a House captures where the writer worked, and makes visible his lifelong study of stasis and movement. In his essay “Dodging Apples,” Price wrote: “all works of art of all sizes—from the Parthenon to King Lear to the briefest Elizabethan lyric, the whisk in the Japanese tea ceremony—have kinetic intent. They came into existence in order to change something (or a number of things)—the actions of a friend, the hatred of an enemy, the savagery of man, the course of poetry, the sounds in the air.”

The pictures of his home illustrate Price’s own “kinetic intent,” as does his estate’s decision to keep his house in use, as a “living document.” It is thrilling to have so loving a look at where he worked for the last 46 years of his life, including the last 27 when he was paralyzed from the waist down, after surviving cancer of the spine. He wrote extensively about what it was like to live in a wheelchair, but his comments were not so much an attempt at explaining his body and its limitations, as his soul and its longings. “I’ve made conscious choices to stay as still as I could,” Price said once in an interview, “so that I could have that kind of position from which to gauge movement. Movement can only be gauged in stasis.”

Those were his poles, in life and art, and he wrote beautifully about wandering while staying grounded in the deckhouse, and then about movement after cancer paralyzed his lower body. Dream of a House doesn’t just document where it happened, but the materials from which Price assembled his thoughts. Readers can study the shelves of bibles, biblical commentaries, theologies, and hymnals to see the research that became his religious books, Three Gospels, A Serious Way of Wondering: The Ethics of Jesus Imagined, and Letter to a Godchild: Concerning Faith; they can trace the jackets and spines of books by Elizabeth Alexander, Emily Dickinson, James Dickey, Dante, and John Donne to learn where Price learned to write poetry like The Laws of Ice and The Use of Fire; and they can turn the pages to see the mixture of Capote, Chekhov, Carver, Colette, Defoe, Forster, and Welty that became novels like Kate Vaiden and A Long and Happy Life.

Those books and manuscripts are part of Price’s biography, but so are the pictures, sculptures, paintings, and statues that represent the friends, idols, family, students, and mentors who were Price’s fellow travelers. These “household gods,” as Price called them, were “images of what I have loved and love and worship—worship in the sense of offering my life and work to them.” Nearly every wall and every surface of the house was tenderly cluttered with these people: their faces, their hands, their backs, their torsos, their smiles and stares. Family snapshots lean against busts of Milton and death masks of Keats, while glamorous headshots of James Dean and Gregory Peck hang alongside Mary Magdalen and the Sacred Heart of Jesus. Price’s younger brother is as likely to appear around any corner as his friend James Taylor, and crayon drawings are hung as carefully Renaissance paintings.

Harris skillfully captures this pantheon. Although Price, who was openly gay, never married or had a long-term partner, it is clear from all of the people whose images populated his home—those who were his contemporaries and those who died long before he lived—that his life was full of love of all kinds. Some of the images are seductive, others sedate; the bodies are sometimes homely, but often homoerotic. Together they populate a life that Price described over and over again as long and happy. “I’ve yet to watch,” he once wrote with equal puck and piety, “another life that seems to have brought more pleasure than mine has to me.”

Price described his creative work not so much as writing, but transcribing. He claimed that he dreamed the dreams of his fictional characters, and that his words came to him effortlessly, as if they were a gift. “I began to understand that my unconscious mind would—to an amazing extent—compose and deliver my novels, poems, plays, and essays if I bothered to give it sane amounts of good food and sleep, sane chemical and emotional nourishment, and then made myself available.”

It was an incarnate view of writing that matched his incarnate sense of the holy. Price wrote persuasively about faith, including his own. He translated portions of the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament, favoring the stories where God revealed God’s self in the world, in particular the messy, fleshy real-life Jesus. He wrote about his own encounter with Jesus in the deckhouse in Durham; having woke one morning with the certainty that he had talked with Jesus at the Sea of Galilee, an encounter that left his sins forgiven and his body, freshly diagnosed with cancer, ready to be healed. Price was a realist writer, but he believed deeply in the palpability of God, and the material presence of the holy in this world.

It is tempting, then, to wonder what he would have made of the choice to produce this book instead of preserving his house in amber. No doubt he would have appreciated how much more easily evangelists can carry the Gospel of Reynolds in book form than come all the way to North Carolina to see it in situ. That is one of the real satisfactions of Dream of a House, its ability to let readers see where and how all of Price’s work was written: the desk and the computer, the ink pens, toner boxes, and filing cabinets, the fax machine, clipboards and paperclips, the waste baskets and galleys. The writer is gone, so why should the estate pretend otherwise and leave his things as if they were awaiting his return? By inviting Alex Harris to take these pictures, and letting Santor help pair them so perfectly with Price’s own words, more and more disciples will be able to find their way to Price. His estate invites readers to meet him the way they always have—in his books.