Late last August, The New York Times gave its readers a welcome break from a brutal presidential election, rolling out a heartwarming story of all-American evil and redemption. Jesse Morton, a white man born in rural Pennsylvania, had raised himself from living in the streets of New York City to the Ivy League—while simultaneously becoming one of the “most prolific” Al Qaeda recruiters in the United States. Then, while serving prison time on terror-related charges, Morton had become “100 percent deradicalized,” cooperating with the FBI as a highly valued informant. When he was released after serving fewer than four years of an eleven-and-a-half year sentence, he’d worked undercover to identify potential terrorists for the feds. And now, Morton had become the first homegrown former jihadi to publicly “come out,” landing a plum job at George Washington University’s Program on Extremism as a researcher and resident terror expert.

The school was eager to publicize his hiring, touting Morton’s “unparalleled blend of experiential benefits and academic insight.” It was a groundbreaking hire. In Europe and Canada, reformed jihadis have taken public roles for years, advising law-enforcement officials and working with NGOs that help rehabilitate “formers” and try to reach potential recruits before they’re radicalized. But in America, Morton was a novelty. And on the heels of the glowing Times story, he quickly became semi-famous, his story retold on CNN, Showtime, PBS, and Fox, among others. Americans love a redemption story, after all, and it was hard to imagine one more dramatic or with a more satisfying denouement. “Now you’re with the good guys,” Bill O’Reilly said when he interviewed Morton on Fox. “Now you’re a patriot—I hope.”

It didn’t hurt that Morton appeared to come straight from central casting. Handsome and impressively erudite, he spun out the plotline of his fall and rise so fluently that it sometimes sounded like he’d memorized a script. When he explained his road to terrorism and back, Morton’s blue eyes often welled up with tears; when he was asked a probing or personal question, he’d tilt his head a little, take a thoughtful pause, and gaze straight at the interviewer before responding.

Here, it seemed, was an uncomplicated spark of hope, radiating through the murky uncertainties and anxieties of the terrorism threat: a man who’d led others down the path to extremism and now was dedicating his life to helping the government and counterextremism groups understand what draws them to such a cause in the first place. Morton quickly became a “poster boy,” as one leading activist put it, for the burgeoning countering violent extremism (CVE) movement that had sprung up under President Obama.

But beneath the Hollywood narrative were questions that cut straight to the heart of our anti-terrorism efforts. No one really understands why some people become radicalized—or how to stop them from acting on it. Law enforcement, in its efforts to prevent violence before it occurs, is also largely shooting in the dark. Given both the uncertainties and the urgency of fending off the terror threat, the impetus to turn to someone like Morton was understandable. But though it was only a slender subtext in the heroic stories he and others were telling, Morton had also been—like pretty much all the other Americans who dedicate themselves to jihad—a deeply troubled young man: in his case, an addict with bipolar disorder who had, before becoming a disciple of Osama bin Laden from afar, landed in jail multiple times on drug charges. Was this the sort of person we should be relying on for intelligence—or setting up as a role model for former extremists?

Morton’s path to salvation seemed almost too good to be true. Could the transition from jihadi to patriot really be so seamless, so rapid, so complete? The answer to that question would, within months of Morton’s sudden burst of fame, become painfully clear. The answer was no.

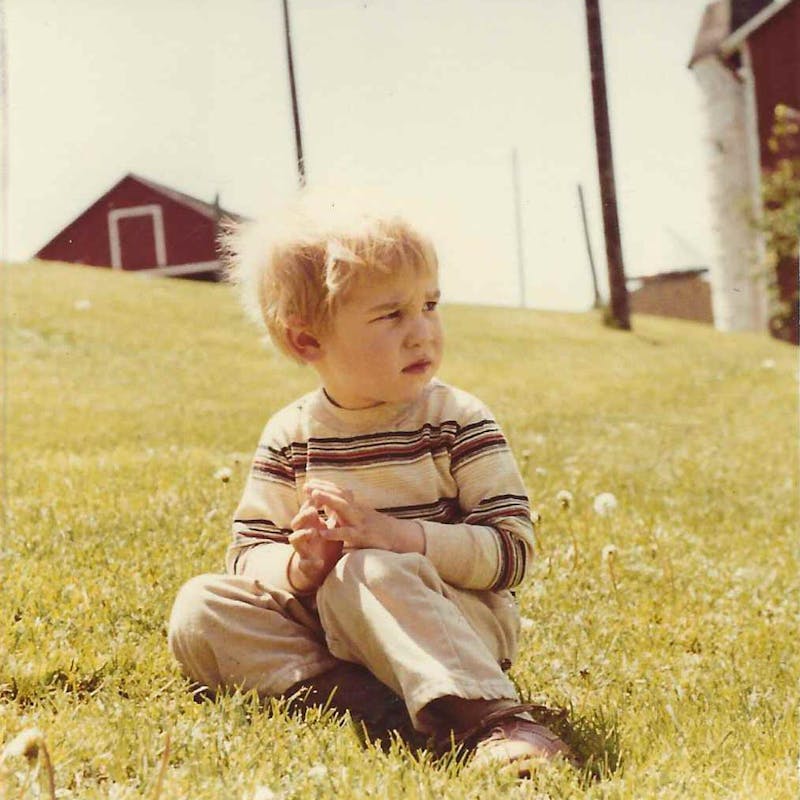

According to family lore, Jesse Morton’s first word was “light.” But as he told me in a series of interviews throughout this summer, it’s the darkness he remembers the most. He was born in 1978 in rural central Pennsylvania to a construction-working father and a stay-at-home mother with a rocky relationship. His mother took her rages out on Jesse, the oldest of three. His first memory, he says, is when she tried to smother him with a pillow.

Jesse was precocious, says his father, George. He talked a mile a minute and was unusually focused on his goals. “He would go full tilt,” George says, at whatever he was doing. He still remembers the boy at age six, practicing baseball drills, over and over. But his kids “went through hell,” George says. At his sentencing hearing in 2012, Jesse testified: “Every day I was choked, bit, scratched, punched, pulled, and perhaps worst of all, insulted.” He tried, he says, to protect his younger siblings—“I adopted the position of savior”—but that only made things worse. His grandmother submitted a letter to the judge describing the bite marks his mother left on Jesse. In her own letter, his mother acknowledged hitting Jesse frequently. “God forgive me for what I’ve done to that child,” she wrote.

When he’s asked how he wound up on an extremist path, Jesse usually connects it to his rough childhood. But his first radical act wasn’t turning to religion, but to drugs and the Grateful Dead. At 16, Jesse ran away from home, winding up at a drop-in shelter near Manhattan’s Port Authority. When the Dead came through New York, he joined a group of the band’s followers on their way upstate. For the next few years, he became a professional Deadhead, following the caravan across the country and camping in open fields, selling acid at shows. He’d buy sheets for $200 and sell them for $300. “I would watch people get high off my LSD,” he says. He loved to see them dance. “That’s what I got off on.”

While he relished the sense of “belonging” he got with the Dead, Jesse also enjoyed guiding other people through their trips; he likens it to the way he’d later nudge Muslims into radicalism. “It’s the same personality trait of having to be in control and liking to watch myself influence other people’s behavior,” he says. “It was sort of like a power-tripping thing, liking to see myself like that.”

At 20, while jailed on drug charges, Jesse read The Autobiography of Malcolm X, which led him to the Koran. Reading it for the first time, he says, overwhelmed him with emotion. “I felt different than I ever had before,” he says. “Just broke down in tears. I was tired of living the way I was living.”

Younus Abdullah Muhammad was born during a subsequent jail stint, in Richmond, Virginia, where Jesse met a Moroccan veteran of the Afghan jihad behind bars. “I don’t like to say he radicalized me,” Jesse says. “I was totally willing and open to the idea.” The man walked him through his interpretation of the Koran, talked up the caliphate, and gave his charge a new name: Muhammad, for the name of the Prophet; Abdullah, meaning “servant of Allah.” And because he was in jail, in “the belly of the beast,” he was also Younus (Jonah), the messenger who ran from God and was swallowed by a whale. “When you return,” he was told, “you need to be like Jonah and call your people to Islam.”

Rather than rejoin the Dead, Jesse moved back to New York City, living in the shelter system again and starting to preach. “I became real popular, real quick,” he says. “I was the white Muslim. Everybody would come up to me. I knew about Islam. I was like a celebrity.” When he started winning converts, he thought to himself, “I’m Malcolm. I got powers.”

One fateful day, he attended New York’s annual Muslim Day parade. He was “disgusted” to see the faithful so patriotic, with their faces painted red, white, and blue. Then he saw a black flag waving in the distance. The banner belonged to the Islamic Thinkers Society, a local offshoot of Al-Muhajiroun, a British jihadi group. When he caught up with them, one of the men took down his email address and gave him an I LOVE JIHAD T-shirt. Before long, Younus Abdullah Muhammad was a vocal leader of the group, stationing himself with a bullhorn outside mosques in Queens, Brooklyn, and Manhattan, warning mainstream Muslims they needed to “see the United States as the enemy it really is!”

At the same time, with the newfound discipline he’d found in Islam, Jesse was raising himself out of homelessness. He went to work as a drug-abuse counselor while attending the Metropolitan College of New York. After graduation, he earned a master’s degree at Columbia University in international affairs. He married a Moroccan native and they had a son. “I had two completely different lives,” he says.

At an Islamic Thinkers Society meeting, Morton met a young Muslim convert from Judaism, Yousef al-Khattab. Both became devoted students of Abdullah al-Faisal, a radical Jamaican cleric. In 2007, they decided to spread the message with their own Al Qaeda propaganda outlet. Revolution Muslim “was his brains and my big mouth,” says al-Khattab, who later served 27 months for threatening Jewish organizations with violence. Morton helped run the web site and online forums, becoming the public face of the group and styling himself as its intellectual leader. “The mujahideen are still waging a successful jihad, but the majority of Muslims cannot foresee the justice of an Islamic state,” he lamented in 2008. “We must pose and become the solution to this paradigmatic problem.”

Revolution Muslim attracted “some pretty crazy people,” says al-Khattab. At least 19 people “associated” with the group would ultimately be arrested, mostly for foiled terror plots. Colleen LaRose, better known as “Jihad Jane,” subscribed to Revolution Muslim’s channels and planned to murder a cartoonist before her well-publicized arrest. Antonio Martinez, who had also watched Revolution Muslim videos, tried but failed to bomb a military recruiting station. Jose Pimentel, who once told Jesse he was a “big fan” of the site, schemed to assassinate U.S. military members.

For almost three years, Revolution Muslim walked a fine line between free speech and illegal incitement to violence. But it was far from a stealth operation. In 2009, the group made headlines by posting a “thank-you” note to the Fort Hood terrorist, calling him “an officer and a gentleman.” CNN soon came calling, and Jesse was eager to broadcast his message on national television. “We are commanded to terrorize the disbelievers,” he said. They must be forced to “think twice,” he said, “before they go rape your mother, or kill your brother, or go onto your land and try to steal your resources.”

In April of the following year, Revolution Muslim crossed the line after a South Park episode depicted the Prophet in a bear costume. Zachary Chesser, a 20-year-old site administrator, posted the names and business addresses of the show’s creators, along with a graphic photo of Dutch filmmaker Theo van Gogh, who’d been shot and stabbed to death for making a movie critical of Islam. “This is not a threat,” Chesser wrote, “but a warning of the reality of what will likely happen to them.”

The gig was soon up. That July, Chesser was arrested at JFK airport, bound for Somalia to fight with al-Shabab. (He’s currently serving a 25-year sentence at a Supermax in Florence, Colorado.) Four days later, Jesse fled to Morocco, where he landed a job teaching English and witnessed the Arab Spring up close, finding himself admiring the freedom young people were seeking. As he translated an Osama bin Laden edict into English for the web, he says, “a seed of doubt was planted.” The knowledge that he might be arrested at any time was also testing his faith. “You’re going to spend the rest of your life in a prison cell,” he thought. “Did you really believe?”

When authorities caught up with him, Jesse was held for five months in Morocco, where he says he was beaten and denied food. When the Americans finally came to get him, he imagined himself disappearing into his own Abu Ghraib. Instead, he says, the Americans surprised him with small acts of kindness. On the plane, someone asked what name he preferred, Younus or Jesse, and he chose the latter. Someone else placed his Koran back in his hands. On U.S. soil, while he was awaiting sentence in a facility in Alexandria, Virginia, a guard gave him access to the library. He devoured the Encylopaedia Britannica, and developed an avid interest in the Enlightenment philosophers John Locke and Thomas Paine.

Jesse decided to plead guilty to avoid the sharpest sentence. As part of his deal, he agreed to be “debriefed” by the FBI on whom and what he knew through Revolution Muslim. At first, he says, agents brought him binders with photographs of suspected extremists. When he didn’t know the faces, he could sometimes recognize screen names and online identities.

But the agents, according to Jesse, didn’t just want his human intel; they asked for his insights into how Americans become radicalized. “They actually wanted to understand how people like me think,” he says. “Why we became the way we are. What we thought was going to happen.” Jesse was flattered. He won’t, or can’t, say much about individual cases. But he told me how it sometimes worked. When a former American associate wrote to him in prison from Syria, for instance, he says the agents asked him to keep up the correspondence, to prize out information. From the man’s letters, Jesse claims he was able to spot a new terror threat on the horizon: “I knew before anybody that ISIS was about to come into manifestation.”

Jesse says he had no qualms providing “intel” on his former associates. His “substantial assistance” to law enforcement helped him win release after serving just one-third of his already light sentence. (The FBI declined to comment for this story.) But Jesse’s FBI work wasn’t over. On the outside, he would be paid to work undercover.

According to Jesse, a friendly FBI agent drove him to a hotel in Northern Virginia. She left him with a laptop, which would soon be outfitted with monitoring software, and a security detail. He was a free man who wasn’t. Tell no one your name, she said. Instructions will follow.

Soon, Jesse posted on YouTube as Younus Abdullah Muhammad, announcing his release and declaring his thanks to Allah. Wearing glasses, with a printed kaffiyeh around his shoulders, he asked viewers to contact him and send him money. He began to hear from both old friends and new, ISIS-affiliated ones as well. “We were garnering all kinds of intelligence,” he says. In one case, a man approached him at a Muslim wedding, having recognized him from online. “He’s like, ‘Brother, I love you so much for your contribution,’” Jesse recalls. Soon, he “told the FBI and then we opened this investigation.” Jesse even kept tabs on his old sheikh, the Jamaican Abdullah al-Faisal, who was ultimately indicted for his connections to ISIS.

Jesse liked the work; he’d found a new mission that made him feel like a person of consequence. It didn’t hurt that he was being paid—more than $10,000, according to court records in just one case. But his marriage was breaking up. His bipolar disorder was going untreated. For the first time in 14 years, he began to drink alcohol again. He figured he could handle a few drinks, no problem. Islam had been his recovery program—no cigarettes, no booze, no narcotics. But what were his limits now? What did it mean to practice his faith without the fundamentalism?

The government, while it may work with former extremists, provides no rehabilitation program for re-acclimating them to a dramatically new life. This is a growing concern, since nearly 100 Americans imprisoned on terror charges are scheduled for release over the next five years. Jesse says his frequent, clandestine meetings with FBI agents “kept me stable,” while he looked to his work for a sense of purpose. “When you would walk out of a hotel room, having done a debriefing, and knew that you just saved at least two, three, maybe 30 lives, you feel good,” he says. But his handlers weren’t interested in his “women problems,” he says, or anything else beyond his intel. “My ‘treatment’ for leaving prison was to sit in the back of a fucking car with an FBI agent and they ask me, ‘How you doing?’ That was my de-rad. That was my support.”

Meanwhile, the FBI was asking more and more of him. In 2015, 25-year-old Mahmoud Elhassan, a taxi driver, introduced Jesse to a friend, Joseph Farrokh, who wanted to go to Syria and join ISIS. Jesse alerted the FBI, Farrokh made his travel arrangements, and on the appointed day, Elhassan drove his friend to the airport. Both men were arrested. Farrokh ended up with an eight-and-a-half-year sentence. Elhassan, the driver, got even more time—eleven years.

One of Elhassan’s attorneys accused the government of manufacturing the plot with the help of informants, naming Younus Abdullah Muhammad in open court. The judge ordered Jesse’s name removed from the record, but it wasn’t long before The Washington Post revealed that the jihadi arrested just a few years earlier was now assisting the FBI. The story came out in February 2016, under the headline: “The Feds Billed Him as a Threat to American Freedom. Now They’re Paying Him for Help.” That put an end to Jesse’s undercover work. But he didn’t mind, he says. He was already hatching a plan for the next chapter of his story: going public as a former jihadi.

George Morton still listens sometimes to a message he saved on his answering machine in late August 2016. “Hi Dad, it’s Jesse. We just wrapped up the final interview for the media rollout.” His son sounded buoyant, and no wonder. Look how far he’d come. The following Monday, he would begin a new job at GWU, lending his expertise to its Program on Extremism, and tell his story far and wide.

The counterterrorism world quickly became a rich new subculture to mine. Jesse learned to navigate Washington’s web of think tanks and white papers, experts and talking heads. He was one of them now, with a $70,000 salary and a fancy title. He dressed sharp, went to happy hours, and became a regular on cable television. In October, after a speaking engagement, he met the love of his life, a Catholic doctoral student from Madrid named Juncal Fernández-Garayzábal. She was tall and beautiful and 29, a terrorism and human-trafficking researcher herself.

By the time they met, however, cracks had started to show in Jesse’s veneer. On a trip to Boston that fall, he spoke to hundreds of people at a Department of Justice conference. After his talk, he broke down crying. That same week, he spoke to a Boston University class and broke down again when he described his rough childhood. The professor, Jessica Stern, is a leading expert on the psychology of extremism, and she thought he needed trauma treatment. She warned his new employers that Jesse seemed to be spiraling. She tried to connect him with a leading therapist. “This is a guy who has the potential to really have an impact on young people who might be attracted to jihadism,” Stern thought, “but only if he gets help.” He didn’t.

Christian Picciolini, a former skinhead who co-founded the nonprofit Life After Hate, warned Jesse about the mental-health struggles many “formers” face when they disconnect from extremism. “I asked him to be aware of how hard he was being pushed and how hard he was pushing,” Picciolini recalls. He advised Jesse to take it slow. But that’s not Jesse.

Jesse says he never felt fully accepted in the counterterrorism world. While he pushed himself to write an academic paper quickly, to establish his bona fides, he was inundated with interviews and requests from counterextremism experts. Having a former extremist in the fold “gives you the legitimacy,” he says. “If he signs off on what you’re doing, you’re going to get your money. You’re going to get your whatever. I became someone who was constantly barraged with requests.” In another interview he told me, “I felt like I was used. Like I was a fund-raising mechanism.”

He felt more and more, he says, “like an animal in a zoo.” Everybody wanted to hear his personal story, to gawk at the ex-jihadi. They were less interested in what else he might have to offer. “In actuality, you know more about the theology, you know more about the politics, you know more about the foreign policy,” he says. “And you’re not allowed to talk as if you’re capable of sitting down at the table with the academics. And you can.”

At GWU, he struggled to connect with his new colleagues. “Privileged people talk about yogurt, and what they bought on Amazon yesterday. I don’t know how to talk about shit like that.” He felt the class divide keenly. “I’m a 16-year-old runaway with contacts in prison and the hood. I missed the concrete. I missed the people that I was used to being around.”

So he found some. He started going to clubs around the D.C. area. “I would meet a guy at the bar,” he says, “and he happened to be the big drug dealer.” Jesse was once again leading multiple lives: dad, terror researcher and CVE front man, and crack addict with a drinking problem. Juncal saw him sliding and tried to help hold him together. But in December, she flew to Spain to celebrate the holidays with her family. Jesse checked in on Skype every day, until he went silent. “Truth be told, I thought he was dead,” Juncal says. But when she found out that he’d landed in jail, she says, “I knew exactly what had happened.”

Three days before New Year’s Eve 2016, Jesse swung into the parking lot of the Governor’s House Inn. A few miles from the nation’s capital, the 1950s-era motel in Northern Virginia was well past its prime. Over the holidays, it had an especially forlorn air about it, with most of the rooms dark and vacant. But in Room 115, which opened directly onto the parking lot that faced Route 50, a female guest had checked in earlier. She would be waiting inside the blue door for her client, who had (according to police) answered an ad for prostitution on Backpage.com.

It was a set-up. Cops swarmed the parking lot just after Jesse knocked. Around 10 p.m., according to court records, he was arrested with eleven bags of cocaine, packaged inside a Marlboro cigarette box, along with a glass pipe with burnt residue. In Jesse’s car, police discovered $965 in cash and a device for smoking crack. These were the remains of a bender that had gone on for days—or was it weeks? Time had blurred.

Soon, The Washington Post had another sensational story: “Man Who Turned Away from Radical Islam Arrested on Drug, Prostitution Charges.” Within days of his arrest, Jesse was fired by GWU. When he posted bail, his probation officer urged him to go straight to the hospital and check himself into treatment. Jesse refused, he says, because he lacked health insurance. Nearly a month after his arrest, he tested positive for cocaine. A judge sentenced him to 90 days in prison, along with 30 days in rehab.

“I didn’t know what was happening to me,” Jesse told me. “I’m sure I’ve had manic episodes before, but that period—I never experienced anything like that. I was, like, really gone. I just left the restraints off.”

Locked up in a federal penitentiary in West Virginia, he sobered up and got back to work. Using a floppy prison-issued pencil, he developed plans for his own counterextremism nonprofit. Rationally, he knew his chances of working publicly again as a former extremist were slim. But he’d made incredible comebacks before. “I went from being on the streets to being at an Ivy League school,” he told me one day when he was feeling optimistic. “I went from being indicted for terrorism charges to being given an opportunity to make amends. So this is just the latest.”

When I first talked to Jesse in May, he’d just emerged from rehab and moved in with Juncal, who’d decided to stick by him. They were living in a low-slung complex of brick apartment buildings just outside Washington, sharing a two-bedroom apartment with three roommates. When I visited in June, Jesse’s son was home sick from school, coloring at a desk in the sparsely furnished living room. Juncal was typing away on their bed, working on her dissertation. On the coffee table, they had put out plates of food: salsa and tortilla chips, pineapple slices, bananas, and blueberries. Jesse was ready to talk.

He was almost always ready to talk, as it turned out. One afternoon, Jesse told me he realized now that he’d made himself a public figure too soon. He wasn’t ready. He’d meant it when he said he was “100 percent deradicalized”—but now, with help from a therapist, he’d come to understand that there’s a difference between disengaging from a radical group and true “de-rad,” a fuller rehabilitation. That was still a work in progress. “I’m working on addressing my mental health complications,” is how he put it.

His therapist has been urging him to give up on the grand ambitions for a while. Wind down, take a construction job—anything that would let Jesse switch off his brain for a while, and also pay the rent. Sometimes he seemed game: “I’ll even dig ditches if I have to,” he told me that first day. But the truth was, he hated the idea. His greatest fear, he eventually told me, had always been following in his father’s footsteps, working construction. “I fight every day to make that not be the case,” he said. Manual labor “is not me,” Jesse said. “I need time with books.”

Almost every time we met or talked, the conversation began with Jesse rattling off his latest projects and schemes. In the first few weeks after his release, a documentary film crew had already come to visit, and The New York Times had interviewed him about a recent terror attack. He had a memoir to finish. He was thinking about a speaking tour, maybe, where he would pass the hat and make ends meet.

In mid-June, I went along as he pitched his nonprofit idea, called Parallel Networks, to a staff member at the Alliance for Peacebuilding in Washington. “It sucks that you have to learn from jihadists,” Jesse told the staffer with a grin, “but it’s just reality.” Jesse was in his element again, and the ideas flowed in torrents. He wanted to create a platform, he said, to promote “principles antithetical to hate and extremism.” He talked of branding strategies—a logo, a social media presence, a web site. There’d be a board of experts. Input from Muslim community leaders. Intervention programs. Educational materials. Anti-hate videos. “If you get more media and you get more propaganda and you get an ability to produce it at the same rate that they produce it,” Jesse said, “now you have a worldview.” It was hard to see how it all fit together—what exactly Jesse wanted Parallel Networks to be, to do. The staffer nodded along, encouraging but skeptical.

There are precedents for reformed extremists to start their own groups. The U.K.’s Maajid Nawaz, for one, a former member of an Islamist group, co-founded the Quilliam Foundation, which has received millions of dollars from government and private sources to combat violent extremism, but he has also courted controversy. Nawaz has pushed anti-terror initiatives so eagerly that the Southern Poverty Law Center listed him as one of its top 15 “anti-Muslim extremists.” He has also been charged with embellishing his biography, as well as the severity of his past extremism, to court fame and fortune.

“This kind of work creates the incentive to exaggerate an extremist past,” says Arun Kundnani, an NYU professor and terrorism researcher. “It’s a commodity for you in this business.” And of course, there’s also incentive for others in the counterterrorism community to play up extremists’ expertise and value. Before his latest arrest, Jesse was a public-relations boon for law enforcement, partly because his deradicalization narrative was largely uncritical of law-enforcement tactics.

One of Jesse’s most influential defenders, former head of NYPD intelligence analysis Mitch Silber, is hardly an unbiased observer: Silber has long championed the controversial surveillance tactics that have come to dominate America’s anti-terrorism efforts. In 2012, when the Associated Press won a Pulitzer Prize for uncovering the NYPD’S clandestine surveillance program, calling both its legality and its effectiveness into doubt, Silber defended it in Commentary, and in a law journal, using Jesse’s case—which he oversaw—as evidence of how effective the program was.

When I interviewed Silber in July, I asked him how influential Revolution Muslim had really been; its web site, after all, had been pretty amateurish. “You say amateurish,” Silber retorted. “I say authentic.” He insisted that Revolution Muslim was actually more important than people know—a precursor to ISIS’s social media strategy, in fact.

Jesse often boasts of the reach and influence Revolution Muslim had. But he says he never considered committing violence himself. He never traveled to the Middle East to fight or train, either. He’d merely been a propagandist for the cause. “I didn’t go to jail for telling somebody to cut a person’s head off,” he told me one day. “I didn’t go to prison for planning an attack,” he said. “I went to prison for being a loudmouth and saying that I believe that I could understand and empathize with the terrorists. I went to prison for somebody else’s post on my web site.”

Everyone I spoke with in the CVE movement still believes Jesse has important contributions to make—if he can get out of his own way. Lorenzo Vidino, his former boss at the Program on Extremism at GWU, stands firmly by the decision to hire Jesse. “This is somebody who has invaluable insights into the radicalization process and great ideas about how to counter it,” Vidino says. But when I asked Jessica Stern, who’d been one of Jesse’s steadiest and most vocal champions, whether she trusts him, she took a long pause. “No,” she finally said. “Not completely.” She didn’t question that he was, in fact, a reformed extremist. “But do I think he’s a reliable person at this point? No. Do I think he’s going to go out and be a terrorist and kill a lot of people tomorrow? No.”

In September, Jesse finally embraced his temporary reality and began working on a construction site’s demolition crew, ripping out wires and breaking out old glass. He knew he needed to slow down, focus on his family and his sobriety, he told me one afternoon after Friday prayers at the mosque. “I have to,” he said, “because if I blow up one more time, I’m either going to end up dead or I’m going to end up in prison for the rest of my life.”

Even so, things are still happening; things are always about to happen. He’s co-writing an academic paper with Mitch Silber. Thinking about making educational cartoons. Or a podcast. Consulting work might be in the offing. A prominent director had gotten in touch, he said, about teaming up on a film about his life.

It would make quite a movie—the epic story of Jesse Morton’s falls and rises. The only thing a screenwriter would have to invent was an ending. But Jesse, it turns out, had already thought of that; in prison for his spree last December, he’d started working on a screenplay.

One afternoon, he recounted an early version of the draft to me. It was a love story. It was a terror story. It was a lot like Jesse and Juncal’s story. In New York City, a young Muslim man starts to associate with jihadis, but as he does, he meets a young woman of another faith (this time, Judaism) who’s studying journalism at Columbia. The two fall in love, despite being on opposite sides of the Palestinian-Israeli crisis. Even so, the jihadi decides to become a suicide bomber. Strapped with explosives, ready to detonate himself, he sees his girlfriend and faces a choice: love or terror? The movie appears to end with a decision to detonate, as horrible carnage is shown. But then we learn that’s a dream sequence. The hero, in the end, finally chooses the better path.