The first full day of autumn felt like midsummer in West Baltimore, and Ben Jealous was sweating with his blazer off. Jealous is running for governor, and he had stopped in for a quick campaign hit at a block party just outside the McCulloh Homes housing project. (Aficionados of The Wire will recognize this location as the site of D’Angelo Barksdale’s drug business.) A large, cheerfully intense man in his mid-forties, Jealous seemed happy to be doing a little grassroots gripping and greeting. Volunteers from Communities United, the local social justice group that had organized the event, had set up a table. A name and address for their mailing list got you a bright purple T-shirt emblazoned with the group’s slogan: ENGAGE EDUCATE EMPOWER. In the shade of a few trees, someone had a barbecue going, smoke spiraling up through the branches, and everyone crowded around for some food and to keep a polite distance from Jealous, who has the kind of charisma that can draw people to him even while he’s perched awkwardly in a folding chair and mopping his brow. A young mother, seated with her child in the stroller next to her, had Jealous cornered, speaking quietly to him about the lack of recreation centers for children in the neighborhood. Jealous listened intently, displaying the politician’s gift for conveying his total attention to anyone with whom he speaks.

Jealous spends a lot of time in this part of Baltimore. In May, he declared his candidacy at Baltimore Blossoms Studio, a nearby flower shop owned by a woman named Rachelle Bland. The location was purposeful—Bland is Jealous’s second cousin—but not just because of the family connection. Baltimore Blossoms is located on an economically depressed commercial corridor that hosts a string of unassuming businesses that most anyone who grew up in a black neighborhood in America would recognize: There’s a deli serving every wonderful fried thing, a barbershop, a hair salon. But beneath the comforting community landmarks lies a palpable sense that justice needs to be done and soon. The shop is a short drive from Mondawmin Mall, the place where the 2015 Baltimore uprising, sparked by the police killing of Freddie Gray, began. Jealous looks here for his constituency. These are the people he wants to connect with and to represent, not just those in the whiter, wealthier suburbs that typically get to choose our leaders.

“My grandmother was a social worker in Baltimore for 30 years. My grandfather was a probation officer at city courts for almost 30 years,” Jealous told me. “They raised me with the understanding that the only way that communities in Maryland get stronger, and problems are solved, is if the governor wants it to happen.” He smiled. “In our state, who the governor is matters.”

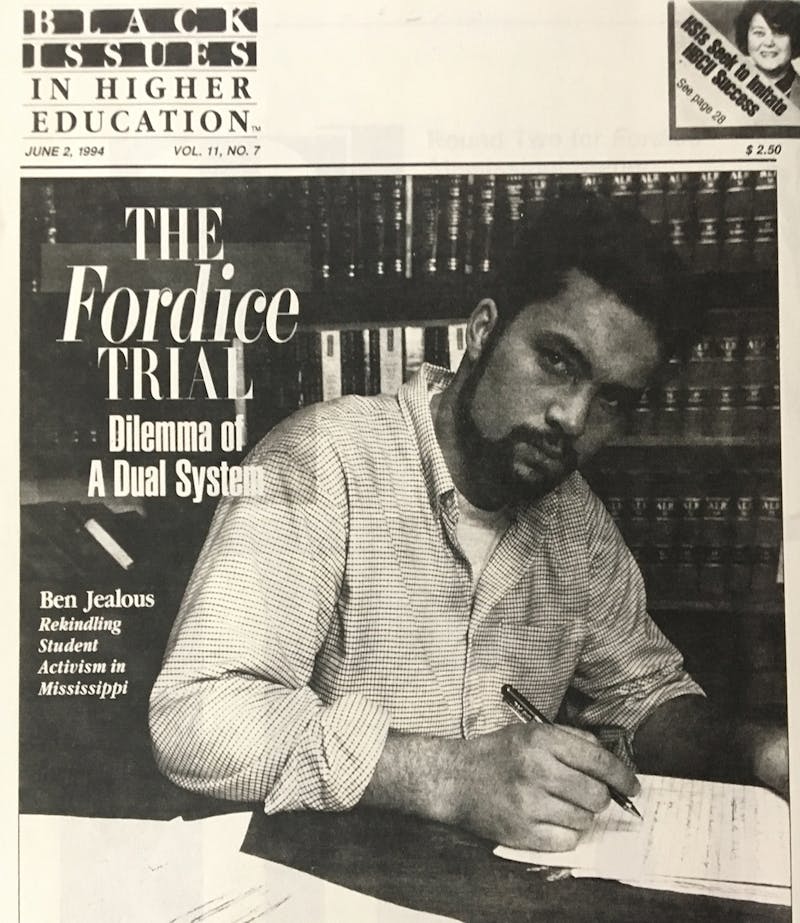

Jealous grew up in northern California, the son of a white man from Maine and a black woman who grew up in the McCulloh Homes. Bland and Jealous go way back: He spent his summers in Baltimore with his grandparents. He got an early start in politics, at age 14, working as a precinct captain for Jesse Jackson’s 1988 presidential campaign. He was a standout student, going to college at Columbia, where he was suspended for a semester for his part in a December 1992 protest over the university’s plan to tear down Harlem’s Audubon Ballroom, the site of Malcolm X’s assassination. The suspension brought Jealous his first taste of national attention. “When you’re the first students suspended from Columbia University in two decades, people take notice,” he said in a 2009 interview with Columbia College Today. “Even when they’re sure all you really know how to do is organize campus protests and get kicked out, they offer you jobs.”

He stayed away from Columbia for two years, working in Mississippi as an investigative journalist for the Jackson Advocate, finally graduating in 1996 and then moving on to Oxford after winning a Rhodes scholarship. When he returned home, Jealous served as the executive director of the National Newspaper Publishers Association, a group of more than 150 African American community publications. At age 29, he became the founding director of Amnesty International’s U.S. Human Rights Program, with a focus on incarceration and racial profilinsg. The same month he turned 32, he moved to the Rosenberg Foundation, a San Francisco group financing social justice projects.

In 2009, thanks largely to the advocacy of the late NAACP chairman Julian Bond, the 35-year-old Jealous was elected the youngest leader in the history of the venerable civil rights organization. It was a close vote. As Ta-Nehisi Coates noted in a 2009 article in The Nation, Jealous’s résumé was considered “peculiar and lacking” by the NAACP board. “He had not pastored a church, he had held no elected office, and he had no direct ties to the civil rights movement.” And yet he prospered. After a string of underwhelming leaders, and some scandalous ones—see Benjamin Chavis—Jealous’s youth, energy, and technological savvy helped reinvigorate the group’s approach to civil rights and community work.

The NAACP’s donor base increased tenfold under Jealous, its annual revenue nearly doubled, and the group’s online engagement went from 200,000 to more than two million. He also got the group back out in the streets, matching the Tea Party rally for rally during Barack Obama’s first term, and marching down New York’s Fifth Avenue in 2012 to protest the city’s ineffective and racially biased “stop-and-frisk” policy. He even urged the NAACP to fight for issues that expanded the group’s traditional mandate. In 2012, ten days after Obama famously reversed himself and endorsed marriage equality for LBGTQ Americans, the NAACP did the same. In 2012, Time named Jealous to its 40 Under 40 list, calling him a “rising star” of American politics. “Where do you see yourself professionally in five years?” the magazine asked. “Exactly where I am right now.”

Then, at the end of 2013, he abruptly stepped down, saying he wanted to spend more time with his family. He decided to become an “impact investor,” backing companies with social justice missions. He is now a partner at Kapor Capital, an impact-investment firm in California. He’s also a visiting professor at Princeton’s Woodrow Wilson School, teaching courses on crime and policing, among other topics. His early endorsement of Bernie Sanders in the 2016 presidential campaign, in which he called him “a principled, courageous, insistent fighter against the evils that Dr. King referred to as the giant triplets of racism, militarism, and greed,” was an early sign that electoral politics might be in his future. His speech at the Democratic National Convention only made that clearer. He combined a plea for Sanders supporters to back Hillary Clinton with a sweeping message of national unity focused on ending racism, transphobia, homophobia, and xenophobia, demonstrating his intersectional view of what an African American leader should be.

His successes since leaving the NAACP seem only to highlight how rudderless the group now appears to be. Shortly after his departure, this country entered a momentous era of social and political foment, the likes of which have not been seen since the height of the civil rights movement. Ferguson, Cleveland, Baltimore, the election of a president whose message embraced outright white supremacy—there has been tumult, there has been protest, there has been activism and organizing and struggle. Yet at the national level, the NAACP has not played a meaningful role in managing or leading any of it. In May, Melissa Harris-Perry published an essay in The New York Times in which she called the group “inconsequential.” It needed to get younger, she wrote, and it needed to get bolder. “If the NAACP is unprepared for emeritus status, it must be ready for a return to the bloody years. It must become radical and expect a time when people will be mocked and potentially even harmed simply for being aligned with it.”

Jealous would never say this publicly, but it is highly unlikely that the NAACP would be judged so harshly if he had been in charge. During the presidential campaign, the African American political establishment threw its support to Hillary Clinton, convinced that her victory would afford them a larger place at the political table than even under Barack Obama. Hazel Dukes, former president of the NAACP’S New York chapter, endorsed her, as did former chairwoman Myrlie Evers-Williams, widow of slain civil rights giant Medgar Evers.

The NAACP, meanwhile, had already ceded the spotlight to its younger, more digitally savvy, less politically centrist counterparts in Black Lives Matter, Black Youth Project 100, Color of Change, and other social justice groups. It is hard to imagine Jealous, with his commitment to technological innovation—Kapor invested in a startup called Pigeonly, which helps direct resources to families with members in prison, and Jealous is on the company’s board—letting this happen on his watch.

Jealous is not, of course, the first NAACP leader to turn from activism toward a run at elective office. Bobby Scott and Al Green both led state-level NAACP chapters, in Virginia and Texas, before winning seats in Congress. Marc Morial, former mayor of New Orleans, followed in the footsteps of his father, Ernest, who ran an NAACP chapter and went on to become the city’s first black mayor. “Campaigning is about organizing, and campaigning is about articulation of issues,” said Morial, who is now president of the National Urban League. Morial knows Jealous well, and in September, both men appeared together at the Congressional Black Caucus’s legislative conference in Washington. “Ben was more than an activist. He was the CEO of an iconic civil rights organization. And he’s now running to be the chief executive of the state of Maryland. Leading the NAACP is an important qualifier to run for an executive job, or to run for office at all.” Cornell William Brooks, Jealous’s successor at the NAACP, put it more succinctly, noting, in the words of one of his friends, that when you run the NAACP, “You’re like the de facto president of Black America.”

That may still be true. But the lessons of the last few years suggest otherwise. At the block party, after Jealous had given up his folding chair, I talked to the young mother with whom he’d spoken. She told me how impressed she was by his interest in local issues, and with his empathy for the needs of the community. She knew he was running for governor, and she hoped that he could do something for people like her. But, I asked, did she know that he’d been the president and CEO of the NAACP?

She shrugged and smiled. “No,” she said. “I had no idea.”

Politicians like to talk about the past when it is useful to them. They are happy to recount old successes, but only if they believe it will earn them a vote. Jealous’s experience at the NAACP is a key selling point of his campaign. That, along with the endorsement he received from Bernie Sanders in July—“Sounds like Maryland is ready for a political revolution!” Sanders said—is why he’s considered a legitimate contender. But it brings with it the inevitable conversations about whether the organization has drifted into irrelevance. Jealous is diplomatic in his comments about the NAACP, to put it mildly. When I visited him at his campaign headquarters, nestled in a small rented home on a side street in Silver Spring, Maryland, he focused on his tenure rather than those of others.

“I came to the NAACP with a series of objectives,” Jealous said, stiffening a little. “One was to elect our first black president. Another was helping to reelect him.” He paused. “A third was to accelerate the end of mass incarceration. Another was to help deliver health care to the millions of Americans who lack it”—he was gaining momentum now—“and another was to be a good ally in the advancing of civil rights generally across the spectrum. We did all of those things.”

It was a nonanswer to a sharper question I had put to him about why he decided to leave the NAACP when he did. But it did suggest that he viewed the NAACP in a very particular way, as a sort of campaign advocacy organization, and not the mass rallying movement-maker that the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. once used to influence and inspire the nation. Which gets to the larger point of why I wanted to speak to Jealous: Why did he think he can do more for America by running for office than by running the NAACP?

There is an urgency to Jealous’s campaign that is completely authentic. It is apparent when you see him on the trail and when you watch him talk to people like the woman at the block party. Donald Trump’s election, and all that it signifies for people of color in this country, along with the sight of Baltimore burning during the 2015 police brutality protests, drive him. Yet if I had hoped to get a direct response from Jealous about why a man of his youth and ability would surrender leadership of this country’s most important civil rights group, I was going to be disappointed. Perhaps he made a simple calculation: Now, more than ever, politics matters more than activism.

In August, West Virginia Governor Jim Justice switched parties for the second time, from Democrat to Republican, handing the GOP control of 34 state governorships. Republicans can now, if they choose, call a constitutional convention and propose any amendments to the Constitution that they see fit. Jealous is far from the only African American leader to heed the call to run. Andrew Gillum, mayor of Tallahassee, Florida, declared for his state’s gubernatorial race in March. Stacey Abrams, a state representative in Georgia, threw her hat into the ring in May. In Maryland, there may be as many as three black candidates in the June 2018 primary: Jealous; Rushern Baker, a Prince George county executive; and Maya Rockeymoore, wife of longtime congressman Elijah Cummings. (Krishanti Vignarajah, the child of Sri Lankan immigrants and a former policy director for Michelle Obama, is also running.)

Jealous expressed enthusiasm for the NAACP’S current leader, Derrick Johnson, calling him “a frontline organizer from Mississippi who has done incredible work in the state.” But the truth is, the NAACP has struggled. It has had three different leaders in the four years since Jealous left. The biggest problem, it seems evident, is that the NAACP still hasn’t figured out how to marshal its forces online. It currently has a few more than 300,000 Twitter followers. DeRay Mckesson, the Baltimore-born civil rights activist, who made his name as an online organizer in the wake of the Ferguson unrest in 2014, has nearly one million. There was once a time when old-guard activists could afford to ignore social media. No longer. It is more than follower counts. The last time the NAACP made national news was when it issued a travel advisory warning African Americans to take care when visiting Missouri, calling out the state’s “questionable, race-based incidents.” This was in August 2017. Michael Brown had been dead for three years. “I think the NAACP is trying to find its footing,” Mckesson told me in a phone interview. Mckesson, for what it’s worth, is a perfect example of the black activists who have proven that social media can be used not only to draw attention to racial injustice, but actually to do the work of organizing to end it. “It’s not clear how the vision has changed, or if the values have changed, to meet the pace of new activism or the new set of issues that have arisen,” he said.

Cornell Williams Brooks was voted out as NAACP head in May after the board decided it needed a different leader to combat the Trump administration’s assaults on civil rights. He says the problem with the NAACP is less about who is leading it than the organization itself. “It does not lend itself to micromanagement-free management,” he told me, somewhat drily. “We have great people, and there is great work being done in many parts of the country. But we don’t have a structure as great as the people.” He didn’t want to get into the specifics of what that meant, but it recalled comments from Bruce Gordon, who resigned as NAACP president in 2007 as abruptly as Jealous did. “I did not step into the role to be a caretaker, to be dictated to,” Gordon said at the time, complaining that his vision for improving African American lives didn’t fit with the board’s. I asked Derrick Johnson about these issues. “The NAACP is 108 years old and has gone through different iterations for how it governs itself,” he said. “With that friction, it builds natural resistance to change. But impact also means change. It is a very dynamic organization.”

For his part, Jealous offered one specific critique. “It is no secret,” he said, “that I advocated to return the organization to being a 501(c)(4) from a 501(c)(3), as it is now.” Jealous declined to elaborate on the consequences of these nonprofit designations for the group—and Johnson pointed out that the NAACP has different arrangements at different levels of the organization—but what Jealous was referring to is that a 501(c)(3) cannot support political candidates, which seems an obvious misstep in an era when voter suppression laws are resurgent. “The NAACP needs to have every option at its disposal, and I know there are many people on the board who agree with me,” Jealous said. “What it chooses to do is obviously up to the NAACP. That’s all that I’ll really say about that.”

The day before the Baltimore block party, Jealous worked a different crowd with the same aplomb. An impressive cross section of the African American elite came to Busboys & Poets in Washington D.C. to hear him speak: Former Obama White House officials and well-known black politicos, in town for the Congressional Black Caucus conference, mingled with a contingent of red-blazered brothers from Kappa Alpha Psi, the African American fraternity to which Jealous belongs. Derrick Johnson was there, too, along with local NAACP leaders, as was Lamman Rucker, star of the Oprah Winfrey Network show Greenleaf.

Jealous gives a good stump speech. Normally stoic and controlled in person, he grew emotional when speaking about his parents. He talked of his love and admiration for the bravery of his mother, Ann, who as a twelve-year-old agreed to act as a name plaintiff for a class-action lawsuit in Baltimore, suing the public school system for segregation. He nearly came to tears when talking about how his father, Fred, was arrested as a protester seeking to end “the systematic humiliation” of the same inner-city students whom he taught in his classes. “I’m very much my parents’ child,” he told me. “They met as teachers in Harlem Park Junior High in 1966. They fell in love. My father proposed three times in their first week of dating. My mom said yes the third time he asked. They’ve been married for 51 years as of this August.” Fred and Ann Jealous had an interracial marriage, which was illegal in Maryland until the landmark 1967 Supreme Court ruling in Loving v. Virginia. Jealous’s parents provided him with a powerful sense of social justice, and an understanding of how productive it can be to act in ways that make others uncomfortable.

Jealous showed he could be funny, too, especially about himself. “I was enjoying being the youngest retired civil rights leader in the country,” he joked. “Doing what you do when you’re retired. You invest a little. You run your mouth a lot.” Laughter burst from the crowd. “But, you know,” he said, pausing for effect, “those of us who put our marching boots on find that it’s hard to take them off.”

Stacey Abrams, who hopes to become the nation’s first black female governor—an astonishing fact in itself—spoke on his behalf. She has known Jealous for more than 20 years, she said, meeting him just after he was suspended from Columbia. “Ben Jealous has always been in the thick of the fight,” she said. “Sometimes he’s starting it, but he’s always there.” The crowd roared.

I followed Jealous to a couple more events, including a town hall hosted by the Maryland Black Legislative Caucus at Morgan State University, and a meeting with businessmen and clergy at a church in Hyattsville, Maryland. Jealous came across as genial and earnest, never letting his audience forget the seriousness of the political stakes. Push through the pet stories and tired anecdotes that are part of any candidate’s campaign rhetoric, and it is clear that the threads of Jealous’s activism intertwine with his political message.

Jealous tends to bristle at the “activist” label, and not because it is politically expedient for him to put his time at the NAACP behind him. “I’m an organizer who, later in life, became an educator and social-impact investor,” he said. “Jesse Jackson. Harold Washington in Chicago. David Dinkins in New York. Doug Wilder in Virginia.” He ticked off the names of historic African American political leaders. “They proved that we could run inclusive campaigns that built a grand alliance of working families of every color—and also win,” he said.

But can he win? Right now, there are eight Democrats in the race to unseat Republican incumbent Larry Hogan. Kevin Harris, Jealous’s press secretary, pointed to a March poll that showed that only 41 percent of voters in the state would vote to reelect Hogan. Fund-raising is the campaign’s current priority, and the true stumping around the state has yet to begin. But Jealous has the highest name recognition of any of the candidates—a direct legacy of his time at the NAACP. And the Sanders endorsement counts, too. Jealous is an official candidate of Our Revolution, Sanders’s newly created political action committee, which means he will receive funding and expertise from the national group.

Hogan seems oddly immune to Trump’s unpopularity. He had a 62 percent approval rating in a late-September poll, same as in February. Elected in 2014, Hogan likes to call himself a centrist, inviting the ire of conservatives for his support of issues like the removal of Confederate statues. But he has also made some unpopular decisions that Jealous intends to exploit. Hogan upset communities of color and city officials in Baltimore by spiking a $1.5 billion redevelopment project for State Center, a 28-acre municipal office complex, and a $2.9 billion expansion of the Red Line light-rail system. The Red Line decision, in particular, was seen by Marylanders as an act of discrimination against black people. One local media outlet called it “anti-urban racism,” and in December 2015, the ACLU and the NAACP filed a joint complaint with the Department of Transportation protesting Hogan’s decision. It’s the kind of political mistake that can get a newcomer like Jealous elected governor. “Larry Hogan has betrayed Baltimore again and again,” Jealous said. “He redlined the Red Line. He stalled the State Center project. Even now, he’s repeatedly refused to listen to the people of Baltimore. He seems to have a reflexive disrespect.”

Jealous has his share of canned lines—a story about a Republican from red-leaning Catonsville, Maryland, quoting Maya Angelou on racial unity, comes up frequently—but he still speaks in the frank tones of a community organizer, not a professional politician. “People are ready,” he told me. “People are tired of despair, tired of angst. They’re ready to recognize the hope that’s evident when we come together, put our burdens on the table, and recognize, as that man said to me, and Maya Angelou before, we have more in common than we have uncommon.”

I felt a twinge of sadness at Jealous’s progress as a candidate: What would the NAACP be doing if he, or someone like him, were still in charge? I was reminded of something Jealous’s cousin Rachelle Bland had told me at Baltimore Blossoms. I had asked her about the NAACP and whether Twitter activists had superseded it in importance. She said she knew we were living in an age of social media–driven activism. But it wasn’t true that black people no longer need or care about the NAACP. When they feel their civil rights have been violated, they’re not ringing up the governor, or any other politician. “When something goes down,” she said, “they usually call the NAACP.”