Writing about Joni Mitchell is difficult. The first and clearest fact about her is that she recorded eight genius records in a row in the late 1960s and 1970s: Song to a Seagull (1968), Clouds (1969), Ladies of the Canyon (1970), Blue (1971), For the Roses, (1972), Court and Spark (1974), The Hissing of Summer Lawns (1975), and Hejira (1976). This is the Joni Mitchell whom David Crosby saw play in the Gaslight South in 1967: “She was singing ‘Michael from Mountains’ or ‘Both Sides, Now’ or some other fucking wonderful song, and she just knocked me on my ass. I did not know there was anybody out there doing that.”

Those albums were all recorded in quick succession, and Mitchell kept working for decades afterward, but it is this era of her career that defines her legacy. Very few critics are interested in Mitchell’s career through the 1980s and 1990s, as attested by almost every article collected in the new book Joni: An Anthology. Critics expressed ambivalent delight at her return to music with 2007’s Shine, albeit alongside disclaimers that “Joni Mitchell created such a prescient roadmap for life and love in the 1960s and early ’70s that everything since has felt cryptic by comparison.”

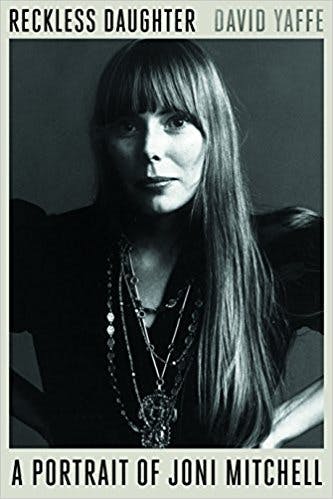

Reckless Daughter: A Portrait of Joni Mitchell, a new biography by David Yaffe, tries to be more fulsome in its treatment of her legacy. It’s a vivid and dramatic book, focusing more on the music than on the musician’s life. Yaffe tries hard to reckon with Mitchell’s genius in prose and to keep up his interest throughout the ‘80s and ‘90s, after her career slumped. Reckless Daughter is an exercise in describing one art form with another, and Yaffe strains to match Mitchell’s musical talent with his own writerly flourishes. He calls the song “Woodstock” “a purgation.” The book is deeply researched and heavily invested in tracing the process of a day-to-day creative life. If you have no interest in the mechanics of studio recording or the career of Mitchell’s bassist Jaco Pastorius, you may find it a little tiresome. But Yaffe tries to put his arms around the whole Mitchell phenomenon.

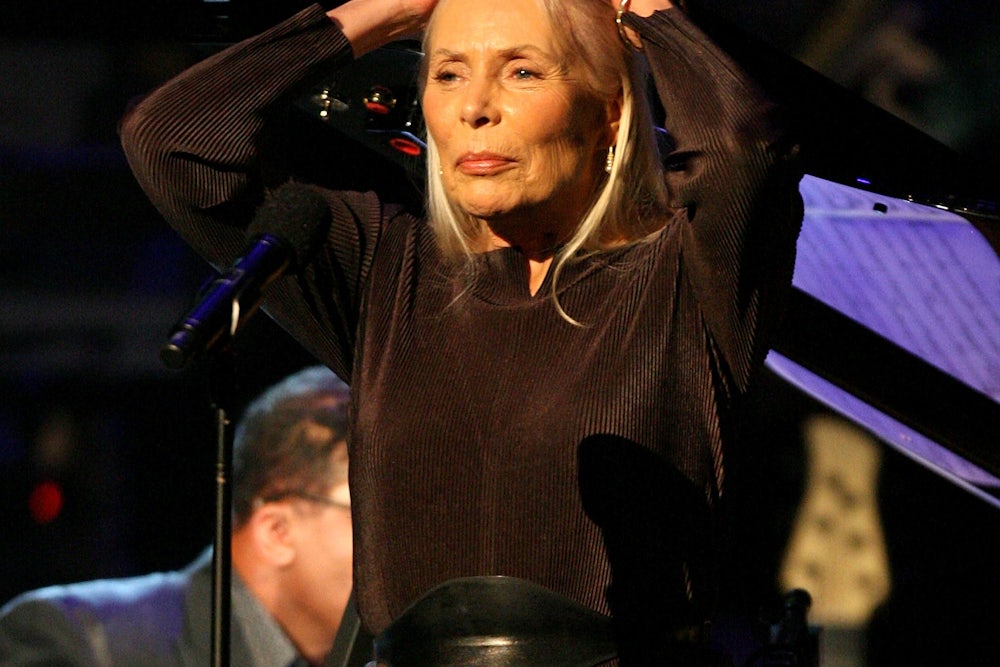

Yaffe dedicates substantial space to what we could call the second Joni Mitchell. This artist is the one who comes after the waifish early years of her creative apex, an ex-folksinger trying to make her way through the ‘80s, getting narcissistic and angry and broke. She makes some bad albums: Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter (1977), Mingus (1979), Wild Things Run Fast (1982), and the synth-soaked Dog Eat Dog (1985). This Mitchell is on a lot of cocaine. Her voice is losing its top end, and she’s bored of playing the guitar in her old style. In 1986, Mitchell played an obscure song at the Amnesty International benefit concert. A dissatisfied audience member threw ice at her face. There follow some better albums in the 1990s, but by this stage, her career is shot and the money is just not coming anymore.

Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter is a specifically upsetting point in this low period because Joni Mitchell appears in blackface on the cover. She’s dressed as a “black pimp” character which she claims was modeled after a man she met on the street (“this black guy with a beautiful spirit walking with a bop”). If you weren’t looking for it, you might not recognize her. Mitchell says that she met the man while on the hunt for a Halloween costume, and she duly went as him to a party, something she repeated on a few occasions. This character seems to have been a long-running fixation of Mitchell’s. As recently as 2015 she told New York magazine that she has “experienced being a black guy on several occasions.” In that interview she seems to say that she feels she has an inner black male inside of her. “I nod like I’m a brother,” she said.

Yaffe also records an incident in the ’70s in which Mitchell deliberately shocked Joan Baez by using the n word in reference to Muhammad Ali and Rubin “Hurricane” Carter. These actions on Mitchell’s part are worth noting, I think, chiefly because they flag what isn’t often said about her.

It isn’t easy to connect this version of Joni Mitchell with the young Mitchell most critics focus on. In her twenties, Joni Mitchell wrote songs that have become girders in the architecture of culture—there are so many covers of “Big Yellow Taxi” that it has hit the U.S. top 50 five times—and she wrote them while being beautiful, white, and female, and playing the guitar in a way that she had personally invented. These facts make her an outlier—contemporaries like Joan Baez and Judy Collins made no equivalent lasting impact—and also transformed the Joni Mitchell of those early albums into an almost mythic figure. Young Mitchell, the one who spat out “The Circle Game” at 23, is such an icon to music fans that she seems to lie beyond the grasp of acceptable criticism. This Joni Mitchell, not the person but the icon, is a fantasy of the bohemian woman, a goddess, a person no more human or connected to the rest of culture than the Virgin Mary.

This is the Joni Mitchell who embodies a kind of bohemian feminine that no longer has room to exist. AIDS and war and the raging capitalist fetish of America showed all the things that Joni Mitchell symbolizes to have been an illusion; the daydream had dissolved by the 1980s. But she was a genius of bohemian fantasy, and so we get to keep her. We’ve given up on that dream, her fans say, but don’t make me give up Joni Mitchell.

By the same token that fans and critics alike idealize young Mitchell into a bohemian fantasy dream girl, they do not scrutinize the complexity, difficulty, and strangeness of her words and behavior in the late ‘70s and onward. It isn’t just that Mitchell fans refuse to let her cocaine-fuelled grandiosity, use of racist language and imagery, or bad ‘80s albums damage her artistic legacy. The problem is that her fans, including journalists, simply do not engage with the whole, real, flawed Joni Mitchell. Our culture’s subtle, insidious misogyny lets us pretend that fantasy women are more important than real ones; the real Joni Mitchell has never existed, according to this logic, and nor does any fan need to reckon with her racist actions in order to obsess over her dainty early music. This dynamic lets us continue loving Joni Mitchell for the fantasy we have of her, a fantasy that was maybe never real—and certainly not since the day she first looked sideways at a synth, and her wrinkles started to show.

I am a biased reader of this biography, because Joni Mitchell’s earliest albums make my skin crawl. Yes, even Blue. I hate the way she yodels, I hate her soprano, I hate the way she pronounces the word “road.” Once all those cigarettes ground her voice down for The Hissing of Summer Lawns, for me, the sound grew into something like music. But her acoustic music relies too much on suspended chords. These are the chords that give songs like “Both Sides, Now” or “My Old Man” a strong aftertaste— like dishsoap not fully rinsed from a glass—of musical theater.

Once Mitchell began playing with accomplished jazz musicians (Yaffe rightfully goes on a long digression on the career of Jaco Pastorius, the genius bass player who transformed her sound) in her mid-career, all those unresolved chords and swooping vocal lines began to make sense. Court and Spark is an album filled with true musicianship, and enough funk sensibility to knock Mitchell’s whistling lamentations into songs.

Perhaps I’m guilty of the same idealization that any Joni Mitchell mega-fan indulges in, except that my “good Joni” exists later, in the part of her career that most critics ignore. Being a fan means being specific about the things you love, and why. A fan gets credit for the music that they choose to define their tastes with. A fan and their chosen star reflect something, a sense of themselves, between them. For that reason, however, we need to trouble our vision of Joni Mitchell as the boho-genius dream girl. Idealizing women into smaller versions of themselves is destructive, even, or especially, when the full picture contains details we’d rather ignore. We deserve both sides, now.