Hobby Lobby stores feel like a second home if you were raised evangelical. It’s Vacation Bible School and Sunday School and girls’ Bible study, located inside one shabby-chic warren. The stores’ owners, David Green and his family—like Chick-fil-A’s Dan Cathy and many before them—have layered a Christ-like veneer onto the pursuit of profit. At Hobby Lobby you can buy a Jesus cross-stitch kit or a poster that reads “This Girl Runs On Cupcakes and Jesus” alongside beads and quilting fabric; it is the store of choice for America’s church ladies, and it has, in turn, made its owners billionaires. The Lord is good—to the Greens.

David Green is an exemplar among Christian businessmen. He stands out not just for his improbably large craft empire, now worth $4.3 billion, or for his religiosity but for the scale of his ambitions. Green and his family have a clear set of beliefs that, they hold, should shape American life: The U.S. is a Christian nation, the archaeological record supports an evangelical Protestant view of the Bible, and Americans should be compelled by law to live according to this interpretation. And they are determined to prove it. In Hobby Lobby v. Burwell, Green’s company argued before the Supreme Court that employers should not have to provide insurance coverage for contraception, if they had a religious objection, and he won.

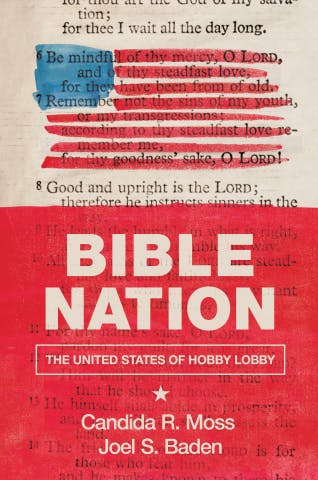

The Supreme Court ruling was far from the pinnacle of the Greens’ ambition, as theology professors Candida Moss and Joel Baden show in their new book Bible Nation: The United States of Hobby Lobby. The Greens “didn’t just want to turn their mom-and-pop homecrafts store into a billion-dollar empire,” Moss and Baden write, “or even merely give back to society once they had made it big. They wanted to play a role in the course of human history. As Mark Rutland, the former president of Oral Roberts University, put it, ‘the Greens are Kingdom-givers.’”

Almost since they opened their first store in 1972, the Greens have mounted a multi-pronged and well-financed campaign to give credibility to and spread their version of human history. Moss and Baden have written the first comprehensive account of that campaign, focusing mostly on the Green Collection, which has purchased a still-unknown quantity of Biblical artifacts; the Green Scholars Initiative, which analyzes those artifacts and produces its own academic curriculum; and the Museum of the Bible, which will open in Washington, D.C. this fall to display the Green Collection’s artifacts. These projects provide a crucial foundation for the family’s theology. For the rest of their evangelical beliefs to make sense—their stance on the role of religion in American public life, for example—they must first defend their understanding of the Bible as a consistent, and literally true, historical record. This is not scholarship for the sake of learning or enquiry, but rather an attempt to prove definitively the truth of conservative evangelicalism.

Exhaustively reported and scrupulously fair, Bible Nation doubles as a portrait of conviction: The Greens may well be the most sincere and most-frequently misguided activists in America. “If they are culture warriors,” say Moss and Baden, “that has been the case for many years.” They’ve successfully shaped the culture they want through the labor practices in their stores, through their philanthropic choices and through their proselytizing mission. Real piety and strategic canniness—it’s a familiar blend. The Green family thinks they need to build their America, but we’re already in it and we have been for a long time.

David Green is a preacher’s son, born in Kansas in 1941. He has never deviated from the faith of his youth, and credits God for orchestrating his rise from poverty-stricken child to billionaire adult. According to one detailed profile in Forbes, Green started his working life as a stock boy, then worked for a five-and-dime store before opening the first Hobby Lobby. Rough patches notwithstanding, Hobby Lobby evolved into a corporate behemoth. But Green’s ambitions were never purely financial. A devout Pentecostal Christian, Green believes that capitalism and Christianity not only work together but require each other.

Moss and Baden correctly connect this belief to the prosperity gospel, which frames financial success as proof of divine blessing. When the Greens make money, they can say God is responsible. This also gives the Greens a perfect justification for almost any restriction they enforce in the workplace. It certainly worked in Hobby Lobby v. Burwell. With its ruling, the Supreme Court delivered the Greens further proof that God blessed their endeavors; the favorable justices took on the form of Moses, handing down divine law. The Greens already believed that moral justifications underpinned their practices; the high court added legal justification too.

When dissent has risen up within the Hobby Lobby empire, the Greens have proved adept at quashing it. Moss and Baden point to a number of lawsuits filed by former employees, alleging gender discrimination, discrimination against employees with disabilities and illegally long hours. We don’t know the outcomes of these complaints because they disappeared into mediation: Hobby Lobby employees reportedly sign an agreement that they will take complaints to a religious or secular arbitration process. Moss and Baden call this unusual, but it isn’t really; many corporations force disgruntled staff into arbitration to keep complaints out of court, and they do it because the arbitration process favors them. The results are private—something the authors do note—and so the Greens’ reputation remains untarnished.

David Green is reportedly worth $6.3 billion now, thanks to this management style and to the American thirst for tchotchkes. But rather than donate the familial fortune to causes that broadly benefit society, Moss and Baden say the Greens restrict their largesse to charities that meet strict doctrinal standards. Indeed, David Green aspires to cosmic impact. “I want to know that I have affected people for eternity,” he has said. “I believe I am. I believe once someone knows Christ as their personal savior, I’ve affected eternity. I matter 10 billion years from now.” David’s son Steve Green, who is the current president of Hobby Lobby and who emerged from Burwell the family’s most public face, speaks often of a Christian “worldview” and his desire to spread it. “The Greens focus exclusively on spreading the Good News,” the authors explain. The OneHope Foundation, Wycliffe Bible Translators, Every Home for Christ: The Greens are committed to the Bible, and want everyone else to be as well.

In July, the Green family made headlines for the other ways they spend their money. After a federal investigation, the Greens had to return $1.6 million worth of clay cuneiform tablets they had bought from Iraq. The money did not, as some initially reported, fund ISIS; but it did prop up a thriving market in looted antiquities and hasten the cultural predation of Iraq. Once these details emerged, the Greens were ordered to pay a $3 million fine to the federal government for smuggling items out of Iraq and mislabeling the shipments; the Greens had called the artifacts “tile samples” and claimed they were purchased from Turkey, not Iraq. “We should have exercised more oversight and carefully questioned how the acquisitions were handled,” Steve Green told NBC News at the time.

Moss and Baden say the Greens started collecting artifacts in 2009, after repeated pitches from Jonathan David Shipman and former Cornerstone University professor David Carroll. According to the authors, Shipman wanted to keep his own Bible museum project afloat; Carroll tells them that Shipman managed to nudge the Greens onboard by pointing out to them that there would be financial benefits to purchasing artifacts. As the authors note, antiquities constantly increase in value, meaning that items in the Greens’ collection are worth more over time, and there are other benefits. “The rationale, again, is a financial one,” they write. “These are objects that can be bought relatively cheaply, but can be valued quite highly for tax purposes.” The project has since expanded beyond Carroll and Shipman, neither of whom are currently associated with either the Green Collection or the Museum of the Bible. But the Greens adopted their ideas with force. By 2010, the Greens had already collected 30,000 pieces—a significant investment for a family that, barely a year before, possessed no real collection at all.

The prospect of Steve Green as Bible-thumping Indiana Jones is a tantalizing vision. But in Moss and Baden’s telling, the family have long been victims of bad actors and their own incompetence. This is where Bible Nation delves deepest, revealing the extent to which the idea that some things must be verified, rather than taken by faith, contradicts the family’s beliefs. The Greens admit that the world of archaeology and papyrology is not their world; that they rely on “experts” to inform them of an object’s authenticity and importance. Yet this has repeatedly led them into trouble as the claims of their own experts have been disputed, and the authenticity of their collections questioned.

Many of the Greens’ prize artifacts are of questionable provenance, Moss and Baden report. Reputable collectors typically establish an artifact’s provenance, or its history of ownership, to confirm that it is authentic, and that it hasn’t been looted from its country of origin. Considering the Greens’ intention to display these items in a museum setting, one would expect them to place particular emphasis on the provenance of their collection. But this is unfortunately not the case. Moss and Baden thoroughly document a disturbing catalogue of errors committed by the Greens and their hand-picked scholars; there are items acquired from eBay sellers, then analyzed by students and academics affiliated with the Green Scholars Initiative despite the fact many, if not most, have little experience in papyrology or related fields.

This means the Greens now possess a fair number of items that lack verified authenticity. Among them: A selection of purported Dead Sea Scrolls. Moss and Baden write that the Green scrolls belong to a “wave” of Dead Sea Scrolls that came on the market in 2002—and that “none” have “any reasonable provenance.” One scholar tells the authors that some of these newly available scrolls are likely forgeries. And there’s more trouble. Green scholars repeatedly destroyed mummy masks in hopes they would find Christian papyri, a practice they assure the authors they’ve stopped. One individual linked to the Green Collection claimed he smuggled a tenth-century psalter across international borders in his luggage.

Many of these artifacts will be on display on the Museum of the Bible, which is set to open this fall despite ongoing controversy over the validity of both the items and the way the Museum intends to display them. The Greens claim the Museum will be non-sectarian, but the act of presenting the Bible on its own, without commentary, is specifically Protestant. Though the Greens have worked with Jewish and Catholic leaders not only for the Museum of the Bible but for previous exhibits, Moss and Baden conclude that they’ve unwittingly facilitated a fundamentally Protestant endeavor—a version of “Protestant triumphalism,” they call it.

Bible Nation is, in part, a family saga. The Greens possess a multi-generational vision not just of a Christian America but of a Christian world, and they suffer from a striking inability to see its contradictions and flaws. The same trait eventually doomed the Greens’ attempt to create a Bible curriculum for public schools, which they tried and failed to place in Mustang, Oklahoma public schools. As I and others reported at the time, the curriculum violated basic First Amendment requirements to teach the Bible as literature or history, not as true doctrine; the Mustang school district eventually dropped the plan. The Greens have since revamped the class, Moss and Baden say, and though it’s more secular than its predecessor it still presents an essentially Protestant view of the Bible. Judging from Moss and Baden’s account, the new curriculum is unlikely to survive a First Amendment challenge if a public school ever tries to take it up.

Steve Green does not seem to understand that the new curriculum has many of the problems of the old one. “My family has no problem supporting those that are out there evangelizing, we do that. But this one is a different role, it has a different purpose. A public school is not the place to evangelize, that’s what the church’s role is; a public school is for education to teach the facts,” he says. In Green’s view, the curriculum he has created does present the facts. He is similarly convinced that the Museum of the Bible is non-sectarian, just as he is convinced that the Constitution does not stipulate a strong wall between church and state. Green genuinely believes he is telling the truth. “We’re buyers of items to tell the story. We pass on more than we buy because it doesn’t fit what we are trying to tell,” he says of his artifacts. It’s not clear that he understands this to be the work of a propagandist.

The Greens are not the sole creators of the fun-house mirror world we inhabit, but they help sustain it. American evangelicals embrace them; the Supreme Court takes them seriously; Donald Trump, a man David Green enthusiastically endorsed, is president and panders to the family’s political allies. The Greens can say whatever they want. This is their nation, and we are their subjects.