I learned to drive on the streets of Karachi. My instructor, per my father’s insistence, was a woman. Every day she showed up in the special instructor car fitted with a brake and a clutch (most cars in Pakistan had standard transmission) on her side. She was not very much older than me but she was, I soon learned, unafraid to ply the streets of the city with smarts and gumption I did not have. Once, when the car got stuck in standing water after a Karachi rainstorm, she told me to open the driver’s side door and look outside. If the water level was a couple of inches below the door, it was okay to drive. It was, and I drove.

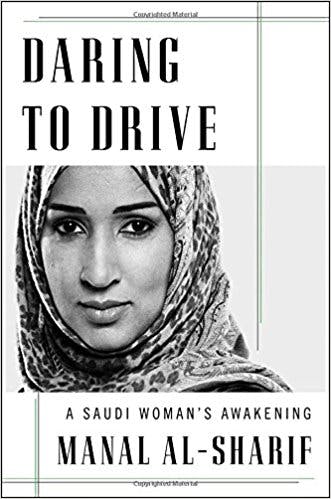

Reading Manal Al-Sharif’s memoir Daring to Drive: A Saudi Woman’s Awakening took me back to those days and reminded me of how contagious courage can be. In 2011, Al-Sharif got behind the wheel of her brother’s car and dared to drive on a Saudi street. She was not the first to protest the Kingdom’s driving ban: Forty-seven women were arrested for doing the same in 1990. But unlike her forerunners, Al-Sharif recorded it all and uploaded it to YouTube. Within hours, a horde of Saudi secret police were deployed to her apartment. There they stayed, carting her off in the early hours of the next morning. Al-Rashid would spend the next nine days inside a Saudi women’s prison, a fate usually reserved for the many migrant women who serve Saudis rather than for Saudis themselves. Al-Sharif would emerge from the ordeal a transformed woman, determined to coax the freedom to drive from the oppressive Saudi state.

Last Tuesday, she won. In a Royal decree issued by the King, the ban on driving was lifted; Saudi women would be able to apply for a driver’s license and drive without the presence of male guardians in the car. The qualms of clerics, who had tried for decades to deny women the freedom to drive, had been set aside by the only man who could: the King himself. In the op-ed she wrote following the King’s decree, Al-Sharif, who now lives in Brazil, declared that she could not wait to drive in Saudi Arabia.

Al-Sharif did not set out to be a rebel. As she confesses, the most rebellious thing she did in her youth was to get a job. But even that was a big step. No other woman in her family had ever done so, and her parents, unsure how to handle it, kept the fact a secret from other family members. It is a telling omission, one that reveals just how unusual Al-Sharif’s family was. Her father was a taxi-driver, who ferried pilgrims between the holy sites of Mecca, where the family lived in an apartment on the edge of a slum. The smell of sewage wafted in the air and relatives mostly stayed away. It was not simply because of their poverty; not only was her father a less than abundant provider, he had a foreign wife. Al-Sharif’s mother was Libyan, a fact that neither she nor her children were ever permitted to forget—cousins referred to her disparagingly (and inaccurately) as “the Egyptian.” This experience, at the margins of belonging, gave her reason to be less than satisfied with the status quo. As she notes frequently in interviews, “not all of us live luxurious lives… spoiled like queens.” In her case, this was definitely true.

But while being an outsider may have left Al-Sharif sensitive to the impact of the Kingdom’s subjugation of Saudi women, she gives little thought to the foreign women who suffer under the same system. When Al-Sharif is packed away to prison, the women inside scream, “You’re Saudi? You’re Saudi?” These women are largely maids and other domestics, who’ve been swept from their homes—in Sri Lanka, the Philippines, Indonesia, Somalia, and India—by global inequality to work in the homes of wealthy Saudis. They are shocked to see a Saudi woman there. Only seven of the 168 women in the prison are Saudi, and of those, four were held in “temporary detention,” not serving out a sentence. Al-Sharif doesn’t offer a comment on this statistic, and during her agonizing nine days, consorted mostly with another Saudi woman.

It is a small quibble but an important one. The designation “Saudi” is, in the Kingdom, a nativist one, available generally only to those whose fathers and grandfathers have been Saudi “citizens.” Obviously this means that the Kingdom’s many migrant workers, like the women Al-Sharif encounters in prison, have no citizenship and hence, few rights. Several have been executed in recent years, some of them on mere accusations of having killed a child in their charge, without trials or investigations or lawyers.

Al-Sharif makes one of her most astute observations when she constructs a genealogy of the Kingdom’s crackdown on women’s rights. She traces the country’s stringent laws to the siege of Mecca in 1979, when a group of rebels took over the Grand Mosque just before the Grand Mufti was about lead a congregation of 50,000 pilgrims in prayer. The rebels, many of whom came from the clerical establishment, were led by Juhayman al-Otaybi, who alleged that the ruling family had strayed too far from Islamic teachings. A bloody siege followed, and when the mosque was stormed over 250 people were already dead, with over 500 injured. To get the clerics back on their side, the Saudi Royal family agreed to implement an even more austere Islam and the Salafist ideology that the Kingdom would impose on their own and export far and wide. Women bore the brunt of this. Their images were censored from every publication and public space. Baton-wielding religious police on patrol became a familiar sight. And of course women were completely banned from driving cars.

If, as Al-Sharif alleges, the elimination of women from the public sphere was the result of strategic imperatives—an attempt to stanch the Pan-Arabism that was spreading across the Middle East, by getting the country’s powerful clerics on side—one cannot help but wonder if recent freedoms are borne of similar considerations. The drive toward self-expression and a desire for democracy has plunged so many neighbors into wars, a fate the monarchy has every reason to want to avoid by handing out small freedoms. In another attempt to appease the populace and institute a kind of protectionism, the Saudi Vision 2030 plan seeks to replace all non-Saudis from government jobs by 2020 and deport thousands of illegal workers. In the new expatriate and foreign worker-free Saudi Arabia, women will need to work—and to drive. Just one day after the announcement of the repeal of the driving ban, a woman was appointed Deputy Mayor of Khobar, the same city where Al-Sharif was detained before being carted off to prison.

Amid the childhood stories and memories Al-Sharif recounts in the early pages of Daring to Drive is an account of her favorite fable. It is the story of a young prince under the tutelage of his older teacher. One day the teacher, suddenly and unexpectedly, strikes the prince. He is shocked, and silently vows to avenge this wrong when he is king. When the day finally arrives, he asks the teacher why he had slapped him. The teacher replies that he did it because he wished the Prince to have the experience of injustice when he was young, so he would understand how his subjects felt when he became king.

There can be little doubt that Al-Sharif’s early experience of exclusion made her a valiant activist. But a feminist awakening requires revolt not only against the wrongs done to oneself or to one’s own kind, but also to those whose humanity is scarcely recognized within the Saudia Arabia and the wider global economy. When Manal Al-Sharif, finally, victoriously drives her car on Saudi soil for the very first time, perhaps she will consider driving to the prison where she was taken, where hundreds of women remain, without any hope of freedom.