In 1982, the late-night talk show host Johnny Carson insulted Jack Kirby in one of the worst possible ways, out of sheer ignorance. As a favor for a small publisher, Kirby had created a comic book called “Battle for a Three Dimensional World.” The artist’s dynamic, eye-popping style was perfect for the format of the book, which came with 3-D glasses reading “Jack Kirby, King of the Comics.” Someone had given Carson the glasses for a comedy routine, sending Carson into an angry riff on national television. Who was this Jack Kirby character, Carson wanted to know, who claimed to be the “king of the comics”? Carson knew every comedian around, and he’d never heard of this Kirby joker. “He’s king of the con men, as far as I’m concerned!” Carson exclaimed.

Jack Kirby, according to his biographer and onetime assistant Mark Evanier, was “deeply, deeply hurt” by Carson’s insults. Evanier wrote to Carson to explain that Kirby was no boastful third-rate stand-up comedian but a legendary comic-book artist, the creator or co-creator of a pantheon of superheroes that included Captain America, the Fantastic Four, Iron Man, the Hulk, the X-Men, the Avengers, Nick Fury, Ant Man, Thor, Black Panther, and scores of others. The moniker Jack “King” Kirby was bestowed on him by Kirby’s collaborator (and sometime foe) Stan Lee. Chastened by the letter, Carson offered a gracious on-air apology.

This case of mistaken identity, one of the many large and small humiliations that bedeviled Kirby’s life, is emblematic of the cartoonist’s curious status as an artist who changed the world while living in obscurity. Born 100 years ago today, Kirby was one of the most influential creators of the twentieth century. He’s as central to the genre of the superhero as Walt Disney is to animated cartoons, Agatha Christie is to detective fiction, Alfred Hitchcock is to film thrillers, or H.G. Wells is to science fiction.

The superhero stories Kirby created or inspired have dominated American comic books for nearly 75 years and now hold almost oppressive sway over Hollywood. Kirby’s creations are front and center in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, but his fingerprints are all over the DC Cinematic Universe too, where the master plot he created—the cosmic villain Darkseid invading earth—still looms large. It was Kirby who took the superhero genre away from its roots in 1930s vigilante stories and turned it into a canvas for galaxy-spanning space operas, a shift that not only changed comics but also prepared the way for the likes of the Star Wars franchise. Outside of comics, hints of Kirby pop up in unexpected places, such as the narrative approaches of Guillermo del Toro, Michael Chabon, and Jonathan Lethem.

If you walk down any city street, it’s hard to get more than fifty feet without coming across images that were created by Kirby or inflected by his work. Yet if you were to ask anyone in that same stretch if they had ever heard of Kirby, they’d probably say, “Who?” A century after his birth, he remains the unknown king.

Jack Kirby earned his obscurity the hard way, by being born into poverty and spending a lifetime relentlessly laboring for the bottom feeders of the publishing world. He was born in August 1917 as Jacob Kurtzberg, the child of Jewish immigrants from Austria living in the crowded tenements of New York. The antagonistic street gangs of Kurtzberg’s childhood neighborhood became the prototypes for the two-fisted combatants he would spend a lifetime drawing.

A compulsive doodler from an early age, Kurtzberg as a teen took jobs as a newspaper cartoonist for a small syndicate and as an animator, doing grunt work for the Popeye cartoons created by the Fleischer Studios. He quickly found a position in the fledgling comic book industry, which was sky-rocketing in 1938 with the appearance of Superman. (Working on superheroes also led Kurtzberg, like many a masked avenger, to don a new identity: he took the name Jack Kirby.)

The early comic book companies were run by fly-by-night hustlers and gangsters, who made their artists (often immigrants or the children of immigrants) work in sweat shops. In that harsh environment, as Evanier details in his art book and biography Kirby: King of Comics (Abrams, 2008), Kirby managed to thrive. He could write and draw faster than anyone else. What Kirby lacked was the gift of gab for selling his ideas to publishers. He needed a salesman partner, and he found one in the form of Joe Simon, who at 6’3” was almost a foot taller than the scrappy but short Kirby and much better at packaging ideas.

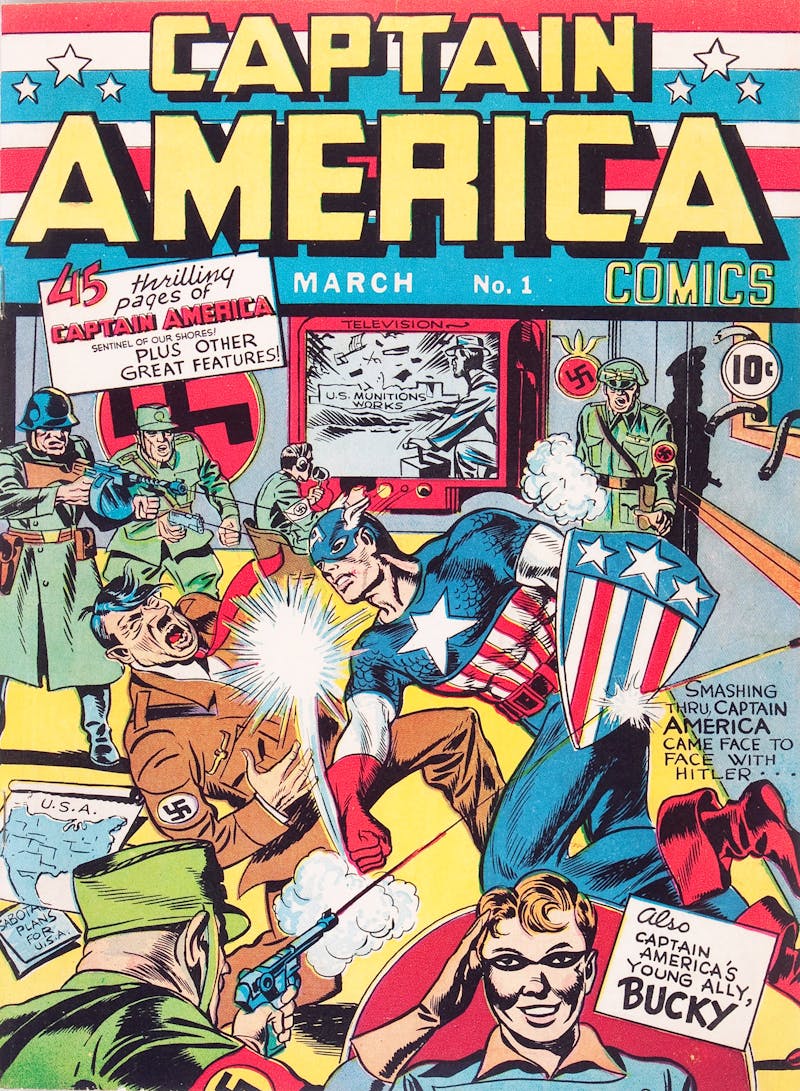

“Simon and Kirby” formed their own studio, which quickly became a byword for success in the comic book industry. Their first big hit was Captain America, a patriotic, flag-draped hero who was shown bopping Hitler on the nose in March 1941, months before America formally entered the war. In still isolationist America, when Hollywood studios were reluctant to feature Nazi villains, the open anti-fascism of Captain America was controversial, and soon Simon and Kirby received enough death threats from Nazi sympathizers that they received police protection.

What distinguished Captain America was not just the politics but Kirby’s kinetic art. Along with his sometime colleague Will Eisner, Kirby was the first comic book artist to quit imitating newspaper comics (with their restricted canvas of a few panels per day) and realize that the comic book format allowed for much more expansive storytelling. “No one put quite as much anatomy into a hero as Simon and Kirby,” recalled cartoonist Jules Feiffer, who started his career as an assistant to Eisner in those years, in his 1965 classic The Great Comic Books Heroes. “Muscles stretched magically, foreshortened shockingly. Legs were never less than four feet apart when a punch was thrown. Every panel was a population explosion—casts of thousands: all fighting, leaping, falling, crawling. . . . They people their panels with Cassius Clays [Muhammed Alis]—speed was the thing, rocking, uproarious speed.”

Like Captain America, Kirby had a chance to fight Nazis himself when he was drafted in 1943. He served in the 11th infantry under General George Patton, landing in Omaha Beach two months after D-Day. For the rest of his life, he told happy stories about fighting Nazis during the day while having nightmares about combat at night. Cartoonist Stan Sakai recalls meeting Kirby at a publisher’s party in the 1980s. “He always told his war stories,” Sakai remembers in the new oral history We Told You So: Comics as Art (Fantagraphics, 2016) by Tom Spurgeon and Michael Dean. “They were different stories, but it always ended with him killing four Nazis. He hated Nazis.”

When the team of Simon and Kirby reformed after the war, superheroes were waning in popularity; their revival at Kirby’s hands was a full fifteen years in the future. But Simon and Kirby proved versatile storytellers in a host of other genres, including western comics (Boys’ Ranch), war comics (Foxhole), supernatural comics (Black Magic), and crime comics (Justice Traps the Guilty). Surprisingly, for a team best known for crafting rough-and-tumble fight scenes, they found their biggest success in romance comics bought by girls and young women. Their title Young Romance sold a million copies in its first issue and would last 208 issues (mostly drawn by other hands). While Young Romance codified the rules of the genre (the confessional story, the heroine torn between competing lovers), it was also driven by a strong subtext of class rage: the heroines often had to overcome social situation where they were blocked by class or ethnic snobbery. Kirby’s own ghetto past infused these plots, giving them an emotional heft that other romance comics lacked.

According to biographer Mark Evanier, Jack Kirby was never happier than when he was working with Simon, but the duo broke up in 1957 when the comic book industry itself was in crisis, in the aftermath of a Senate investigation into comics as a cause of juvenile delinquency. It was in these lean years in the freelance wilderness that Kirby returned to a publisher he had worked with at the start of his career, Marvel Comics, and hooked up with a new collaborator, Stan Lee.

There had long been bad blood between Kirby and Marvel, owing to his feeling that publisher Martin Goodman (who was related to Lee) hadn’t paid promised royalties on Captain America. But Kirby, married and with four kids, was desperate for employment, and Marvel was willing to give him all the work he could handle. By the time he was in high gear in the early 1960s, Kirby often drew more than a hundred pages a month, in an industry where 20 or 30 pages a month was the norm for a hardworking artist.

Kirby and Lee would revitalize the superhero genre in the 1960s, creating a universe of characters from the Fantastic Four on down. It was Lee and Kirby, along with a few other artists like Steve Ditko, who created the Marvel Universe. But they made an awkward pair. Lee was a smooth salesman, while Kirby was an introverted artist. A 1965 article in the New York Herald described Lee as an “ultra-Madison Avenue, rangy lookalike of Rex Harrison,” but said of Kirby that “if you stood next to him on the subway you would peg him from the assistant foreman of a girdle factory.” In cultural style, Lee was management, and Kirby was at best lower-middle-class.

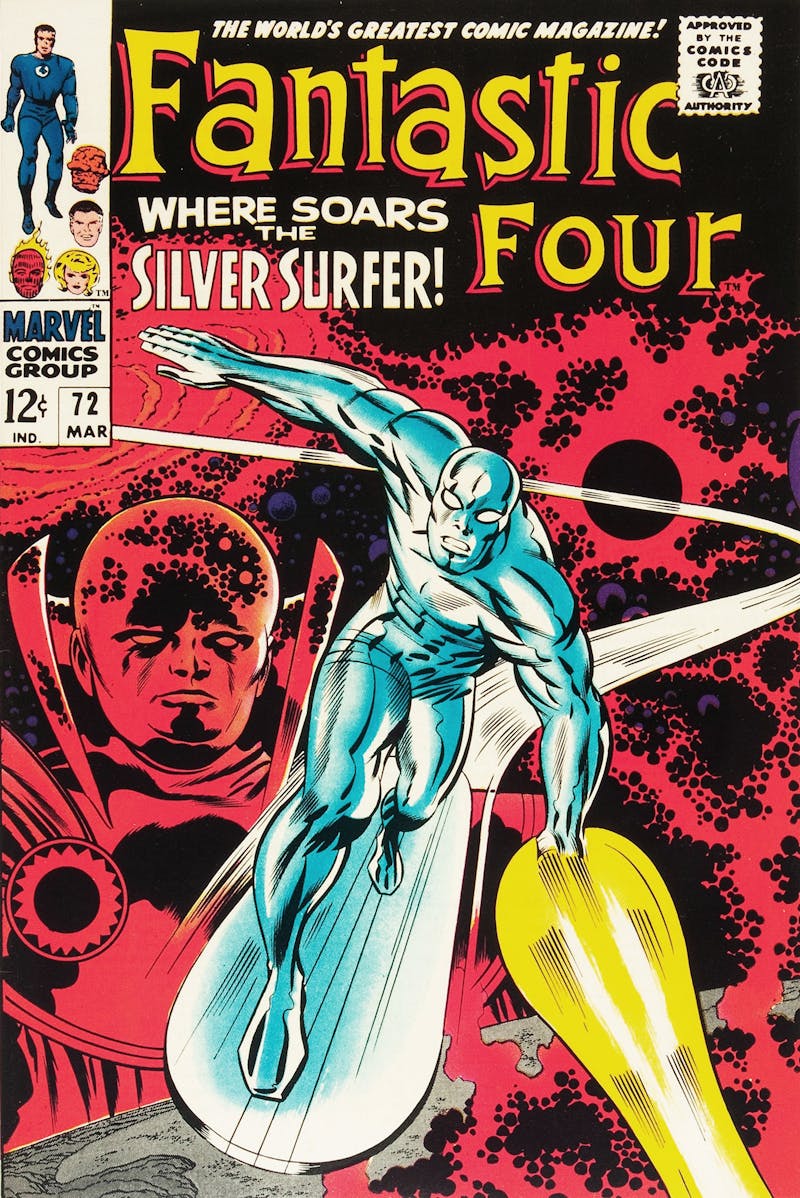

Their working method was an unusual one. To produce pages at the rate that Marvel needed, they didn’t follow the normal procedure of the artist sticking to a tight script. Instead, Lee and Kirby would talk about plot ideas, Kirby would draw out the story, and then Lee would add in dialogue after the fact. As the collaboration progressed after a few years, the first step all but petered out. Kirby was in effect plotting out the stories, and often creating characters (notably the Silver Surfer) with no input from Lee.

If there has ever been an artistic collaboration—Gilbert and Sullivan, McCartney and Lennon, Simon and Garfunkel—that hasn’t spawned arguments about who should get credit for what, I haven’t found it. But these days, the collaboration between Lee and Kirby is hardly even recognized as one. It’s undeniable that Lee’s snappy dialogue and glib patter helped give Marvel comics a hip feel. Often Lee’s banter helped to leaven Kirby’s tendency toward grandiosity. But the characters, themes, and narratives were overwhelmingly produced by Kirby, echoing stories and ideas he had been working on for two decades before his return to Marvel. The super soldiers, the monsters as heroes, the love triangles, the fusion of mythology with science fiction, the teams of disparate warriors brought together by a common crisis: all of these were germinating in Kirby’s work prior to meeting Lee.

“I’ll take any credit that isn’t nailed down,” Stan Lee once said. True to his words, Lee’s accounts of the origins of Marvel comics make it sound like he was the instigator while Kirby (and other artists) executed his vision. Marvel only reinforced this perception when it made Lee’s authorship a part of its corporate mythology, printing a “Stan Lee Presents” logo on countless comics. That Lee, who is still living, makes a Hitchcock-like cameo in what seems like every new Marvel movie further solidifies his fame.

Whatever side of the Kirby/Lee divide you fall on, there’s no denying that questions about collaboration trickled down into their work. The great Kirby and Lee comics of the 1960s were pivotal in remaking superhero comics into something more than children’s fables, and one fundamental addition was the concept of a super-hero team. Earlier superhero comics brought together characters in an ad hoc way. There’s really no reason Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman should have formed the Justice League other than the fact that they were all popular. But Kirby’s teams, as scholar Charles Hatfield notes, were different. They were united by a common experience, whether the trauma of radiation (the Fantastic Four) or of all being mutants (the X-Men) or outsiders (the Inhumans).

Rare among American artists, Kirby was not an individualist. That position was taken to an extreme by his Marvel colleague Steve Ditko, a follower of Ayn Rand. But Kirby himself was formed by groups: the kids’ gangs he grew up with, the Boys Brotherhood Republic (a youth group that steered him away from gangs), the army, and even the Simon and Kirby studio. He had a profound belief that human destiny lies in groups, even if those groups are made up of misfits and freaks. If there is one overriding message in Kirby’s work, it’s a communitarian one: to triumph over evil, we have to come together. Forming such a collectivity is never easy (Kirby’s groups were full of internal strife) but always necessary.

Under the pressure of the intense deadlines he was meeting in the 1960s, when he would produce as much art in a year as other cartoonists do in a decade, Kirby’s rugged realism evolved in a surprisingly abstract direction. He became a kind of pulp Picasso. “His forms became geometric and stylized,” reflected novelist Glen David Gold in a 2005 essay. “Every surface, including human skin, gleaned like chrome. Every starscape exploded with mysterious dots and ‘Kirby Krackle.’” That “Kirby Krackle,” unleashed in scenes of energy or chaos, became a signature device, one that Kirby never explained but that, like so many of his quirks, compelled the eye.

Operatic, sprawling, and mythopoetic, the stories Kirby and Lee worked on remade superhero comics into a form of space opera, taking place in a teeming, lively, and imaginatively exciting universe. The new emotional depth of these comics owed much to the romance stories Kirby had worked on in the 1940s and 1950s. Kirby never really abandoned any of the genres of his past, so the superhero comics he created became a meta-genre, combining aspects not just of mystery-man intrigue but also elements from romance, westerns, science fiction, and horror.

In 1963, a

15-year old who signed his name George R. Martin wrote a fan letter to

the Fantastic Four extolling the comic. Decades later he would achieve fame—with

an extra R.—as George R.R. Martin, author of Game of Thrones. He still credits his early comics reading as

formative. “The Marvel characters were constantly changing. Important things

were happening,” Martin reflected in a

2011 interview. “The lineup of the Avengers was constantly changing.

People would quit and they would have fights and all of that, as opposed to DC,

where everybody got along and it was all very nice, and of course all the

heroes liked each other. None of this was happening. So really, Stan Lee

introduced the whole concept of characterization [chuckles] to comic books, and

conflict, and maybe even a touch of gray in some of the characters. And boy,

looking back at it now, I can see that it probably was a bigger influence on my

own work than I would have dreamed.”

Of course, the qualities that Martin is crediting to Lee came at least as much from Kirby. But such is the power of the Lee myth.

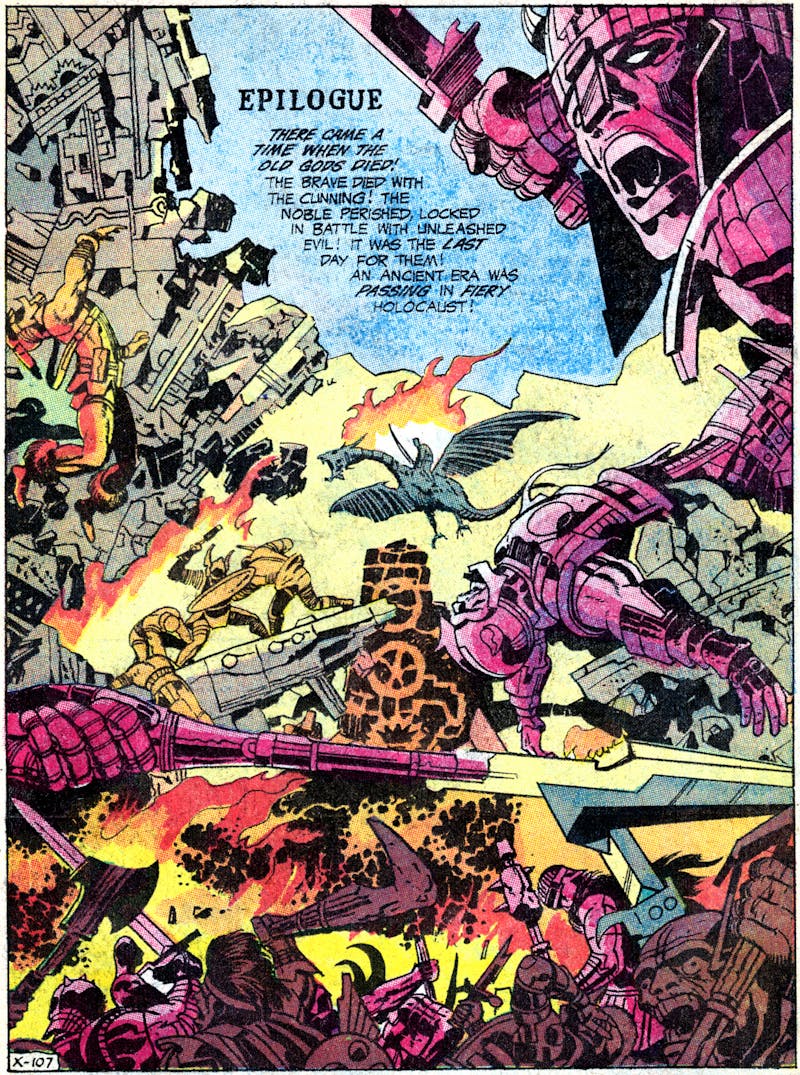

Kirby had a bitter falling out with Lee and Marvel in 1970, as Lee courted the press and the publisher backed away from promises of royalties. Kirby started to do solo comics for DC, producing what is arguably his finest body of work in the ambitious Fourth World series, featuring cosmic hippies fighting the ultimate bad guy, the Nixonian tyrant Darkseid. In these comics Kirby turned the culture wars of the 1960s into allegory, with questing youth battling life-denying authority.

What gave these simplistic dichotomies power was the visual forms Kirby found. The stone-faced Darkseid both updated Kirby’s older masked, cape-wearing Dr. Doom (who fought the Fantastic Four) and anticipated Darth Vader of Star Wars. Indeed, the Star Wars franchise as a whole owes much of its DNA to the Fourth World. Darkseid’s relationship to his son Orion (raised by others and a rebel against his father) prefigures the Vader/Skywalker narrative arc. Darkseid’s home planet of Apokolips, a kind of mechanical hell, could easily be mistaken for the Death Star. The religion in the Fourth World series is “The Source”—just one letter away from “The Force.”

In 1970, DC Comics ran an ad for the Fourth World books that read “so powerful in concept—it’s almost terrifying!” This was no hype. It describes the books perfectly, and George Lucas isn’t the only artist who has cribbed from them. While Kirby’s 1970s work wasn’t always commercial successful, it was eerily prescient. The young people in the Fourth World books are addicted to a handheld device called the Mother Box, which they turn to for answers to all their questions. The Mother Box is essentially a super-smart iPhone avant la lettre. But in the end, Kirby’s lasting gift to popular culture may be the freedom to work in meta-genre. Game of Thrones has elements of science fiction, historical fiction, and horror, as well as fantasy, while the Star Wars franchise is a mishmash of space opera, war films, the western, and samurai movies. For that, we may have Kirby to thank.

Kirby and Lee occasionally worked together after 1970 on a few stray projects, but the bitterness of their break-up never really healed. When Kirby died in 1994, Stan Lee showed up to the funeral, but slunk out before Kirby’s widow, Roz, could talk to him. Kirby’s family engaged in extensive litigation with Marvel comics to win claims of authorship and royalties, and the parties settled out of court in 2014. While Evanier refuses to disclose any information he has on the size of the settlement, he wrote that “if they’re watching this from wherever they are,” Jack and Roz Kirby “are real, real, real happy.” Moreover, Marvel now routinely credits Kirby as a co-creator in both its comics and movies. Kirby’s centrality in creating the Marvel universe is now increasingly recognized.

Jack Kirby—communitarian in outlook, gifted at making others rich but luckless in his own business dealings, and stunningly prolific—remade the world of comics at least three or four times: with his dynamic art, with his popularization of romance comics, with his ambitious space operas, and finally with his late personal work, auteurist experiments that prefigure the graphic novels of Alan Moore and Neil Gaiman. As the superhero genre itself has spread outside of comics into film, videogames, and television, we will only be seeing more of him. Jack Kirby is an unknown king, but a powerful one.