It’s the year 2015, in Paris, and negotiations over an international climate accord are falling apart. India‚ the world’s fourth-largest polluter, is wary about signing onto the deal, fearing the commitments are too strict for a developing country with high energy needs. So Al Gore whips into action—by pulling out his cell phone. He dials Larry Summers, the former U.S. Treasury secretary, and says, “Elon suggested I call.” Naturally, the former vice president is on a first-name basis with the founder of Tesla and SpaceX. But Elon Musk is more important to Gore as the chairman of SolarCity, which The New York Times describes as “the nation’s leading installer of rooftop solar panels and a renewable energy darling.” Gore is thus connected with SolarCity’s president, and asks him to give the company’s intellectual property to India, free of charge. “SolarCity could be the corporate hero of Paris,” Gore says into the phone. “Think about it.” The company eventually agrees, and India signs the agreement. Gore saves the day—and perhaps the planet.

This is not a first-hand account of the negotiations over the now-historic Paris agreement, but rather how they’re portrayed in Gore’s new documentary. On its face, An Inconvenient Sequel: Truth to Power brings viewers up to date on both Gore and the planet since his Oscar-winning 2006 documentary, An Inconvenient Truth. (Spoiler: The planet has been getting hotter, and Gore’s been working to solve the climate crisis.) But the film also completes the lionization of Gore that began with its antecedent. If An Inconvenient Truth cast him as a brave voice in the wilderness, An Inconvenient Sequel is a victory lap of sorts. Gore’s dire warnings have come true, the movie posits, but he’s been working tirelessly behind the scenes to stave off a global catastrophe—and achieving tangible results.

But apropos of this week’s release of An Inconvenient Sequel and a book of the same name, Gore, 69, is thrusting himself back into the spotlight as America’s top spokesperson for climate change activism. He’s granted myriad interviews in recent weeks—including The New York Times, CBS, Interview, Fast Company, CNN, Stephen Colbert, and NBC, but not, alas, the New Republic—to promote his latest projects and deliver a relentlessly optimistic message. “Is there hope, Al Gore?” Colbert asked him. “Absolutely,” he replied. “Go see the movie and you’ll see there is tremendous hope. We are going to win this.” He told CBS, “Those who feel despair should be of good cheer, as the Bible says. Have faith, have hope. We are going to win this.”

Gore’s latest climate campaign is a welcome development to the many environmentalists who consider him an invaluable member of the movement. “Literally no one has brought the climate message to more people of all kinds,” said Bill McKibben, the journalist and activist who co-founded 350.org. “And no one else has insisted as long and loudly that the planet’s elites stay focused on this crisis.” Michael Brune, executive director of the Sierra Club, told me, “He has a deep well of experience and connections to world leaders, and that makes his voice particularly powerful.”

But not everyone on the left is celebrating Gore’s reemergence—and for reasons that sometimes contradict each other. Some worry he’s too polarizing a figure, and therefore could paralyze progress on climate change. “It’s time to start building bridges instead of further entrenching into tribes,” said Eric Holthaus, a meteorologist and contributing writer at Grist. But author Wen Stephenson sees the opposite problem: “If Gore himself is trying to appeal to bipartisanship, I’d tell him to stay home.” Still others are concerned that Gore’s image is at odds with an increasingly inclusive and intersectional movement. “We need to break away from this idea that the Leonardo DiCaprios and the Gores are the ones who will solve this,” said Anthony-Rogers Wright, an organizer at The Leap.

This skepticism about Gore reveals a lot about the climate movement, which has fractured significantly since An Inconvenient Truth. Whereas a decade ago there was a relatively united focus on spreading awareness about climate change, today there is no clear consensus on how to fight it. Should the left work with centrists and even conservatives on policy goals? Should the fossil-fuel industry be courted or coerced? Should climate deniers be educated or mocked? Activists are debating these questions while the movement bleeds, having suffered one blow after another from a hostile administration intent on undoing years of progress under Barack Obama.

Now, amid this identity crisis, the heroic climate crusader returns. But can Al Gore really save the day, or will he only open more wounds in the movement?

As Gore tells it, he had to be talked into this sequel. “I have to tell you that when the idea for the first movie was presented to me, over a decade ago, I was skeptical. I was consistent this time around and skeptical once more,” he told Fast Company. “I guess I was just worried because the first one was so well received. But I’m glad that wiser heads prevailed.” An Inconvenient Truth was more than “well received.” The documentary, a glorified slideshow that cost just $1 million to make, earned $50 million at the worldwide box office and $31 million in video sales. It also transformed Gore from a politician into a cultural celebrity. He was no longer the wooden, failed presidential candidate, but an amiable, captivating climate prophet. Some Democrats even urged him to run for president again. (Some still do.)

Riding high on the film’s success, Gore threw himself into environmental advocacy. But he receded from view after two massive failures for the climate fight: the collapse of international climate talks in Copenhagen in 2009, and the death of bipartisan federal legislation to fight global warming in 2010. “Everybody had to take stock,” said Brad Johnson, a longtime climate activist and executive director of Climate Hawks Vote Civic Action. “Like other people, Gore kind of retreated and regrouped.”

Gore didn’t truly go away. He focused on his Climate Reality Project, which grooms environmental activists. He continually updated his slideshow and presented it around the world—to 12,000 people in 33 countries, and counting. He became a successful green tech investor. As his new film reminds us, he was involved in the 2015 negotiations that led to the Paris climate deal. Last year, he hit the campaign trail for Hillary Clinton. And in April, he joined the People’s Climate March in Washington to protest President Donald Trump’s climate denial.

Over the course of that decade, though, the climate movement has changed substantially: It’s much bigger, and much more divided. And the split is over the most critical question of all: how to win the climate fight. On one side are the inclusionists, who argue that environmental activism must appeal to Republicans and others who are skeptical of the urgency, or even reality, of climate change. Rather than debate the facts or engage in hysterics, they say, the movement should focus on shared values—like, for instance, the economic benefits of investing in clean energy—and recruit trustworthy messengers who can appeal to a skeptical public: small business owners, moderate Republicans, corporate CEOs. People like General Electric CEO Jeff Immelt, former Goldman Sachs CEO Hank Paulson, and Michael Bloomberg.

The purists, meanwhile, argue the only way to win this war is to engage in an all-out rhetorical assault on Republicans and anyone else who opposes climate action, and to target those populations who will be most impacted by climate change. This side advocates a unflinching alarmism: Climate change is both a moral issue, one that disproportionately impacts minorities and the poor, and an existential issue, in that human civilization is at stake. They say the Paris agreement doesn’t go far enough to reduce global temperatures, and that our energy supply must be 100 percent renewable. The idea, as Vox’s Dave Roberts explained well in a recent Twitter thread, is that the left should be unafraid to own climate change because it’s a winning issue. Public opinion continues to grows in favor of climate action, and businesses are increasingly investing in green technology.

21. Cleantech's gonna keep booming. The trajectory is clear. The party that owns this issue will benefit for decades to come.

— David Roberts (@drvox) June 27, 2017

Gore does not fit neatly into either of the camps. At times he’s inclusionist: In An Inconvenient Sequel, he goes to Georgetown, Texas, “the reddest city in the reddest county” of the state, to showcase its full conversion to renewable energy. “It’s just common sense,” the town’s Republican mayor says, “that the less stuff you put in the air, the better.” Gore also highlights his attempts to convince Trump to tackle the climate crisis, a valiant portrayal of inclusion. But other times, Gore leans purist. In an emotional scene, he shows the impact of 2013’s Typhoon Haiyan. A young Filipino cries as he recalls almost dying; another describes breaking through the ceiling of his home to escape drowning. At another point, Gore narrates over helicopter shots of sweeping, devastating wildfires, “Every night on the evening news is like a nature hike through the Book of Revelation.”

This inclusionist-purist tension within Gore is reflected in his interviews of late. He clearly wants to be perceived as a moral crusader, going so far as to say the climate movement “should be seen in the context of the great moral causes that have transformed and improved the outlook for humanity”—citing slavery, women and gay rights, and apartheid. He’s also apparently done reasoning with Trump, telling Business Insider he has “no real desire to talk to him anymore.” But he also clearly wants to be a uniter, dismissing fear as a messaging tactic. He told Fast Company that “despair can be paralyzing, and the fear of these consequences is not necessarily the most effective way to change minds and motivate people. But when you can convey hope in a realistic way, that unlocks a higher fraction of the potential for change.”

It’s perhaps because Gore is so hard to pin down on the activism spectrum that he’s become such a divisive figure. But the criticisms of him may say more about the climate movement than about Gore himself.

Gore is the most polarizing figure in climate politics—disputed on the left, and widely loathed on the right. According to research by environmental scholar Andrew Hoffman published in 2011, nearly 40 percent of all articles casting doubt on climate change mentioned Gore. “He had become extremely provocative for many people, and that limited his voice,” Hoffman told me. “Now that he’s stepping back into it, we’ll see what happens.”

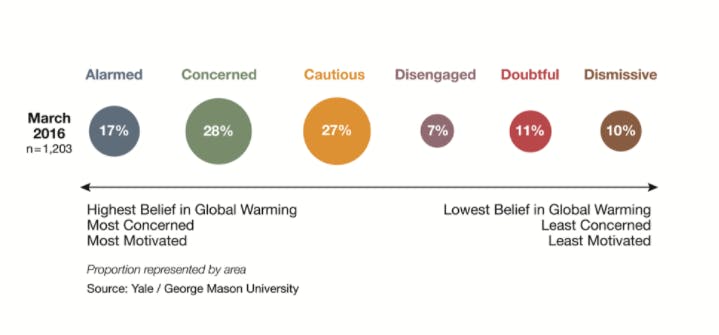

Gore’s return has provoked a predictable reaction from the right. Senator Jim Inhofe mocking him on the Senate floor. The Daily Caller dubbed the new film “climate narcissism.” This reception from conservatives corners raises red flags for inclusionists. “I think reaching new audiences is key,” said Holthaus. By “new audiences,” he means people who aren’t already alarmed about climate change—which is the majority of Americans, according to research from the Yale Climate Communications Project.

Hoffman and Holthaus agree that it’s useless to try to convince firm climate deniers to change their minds. But for the “undecided middle,” they believe the messenger can be more important than the message. “When Al Gore or the Environmental Defense Fund or the EPA say climate change is going to effect our lives, people might tune out,” Hoffman said. “When the CEO of Carlson is saying it, though, that has tremendous impact.” Make no mistake: Gore is great at motivating people who are already worried about climate change. But when it comes to winning over others, he may be doing more harm than good. “He will appeal to those who already believe climate change is real,” Hoffman said. “He will become a lightning rod for those who don’t.”

The idea of appealing to “new audiences” also means appealing to people who aren’t white and well off. “That’s a weakness of Gore, quite frankly,” Rogers-Wright said. “He certainly understands the science, and he’s given some amazing TED talks. But he has not really showcased this issue of environmental justice, which is disappointing.” An Inconvenient Sequel does touch on the subject: Gore cites a Pope Francis quote about how climate change disproportionately hurts poor people, and says, “This is true everywhere in the world.” But some activists don’t believe Gore is the right messenger for that fight. “I think we need to see more folks of color, climate justice advocates, who are on the frontlines of climate change to rise to the level of platform that he has,” said Michelle Romero, deputy director of Green For All. That’s something inclusionists and purists tend to agree on. “[Gore] is a relatively old white male who has a very polarized following,” Holthaus said. “I think the overall climate conversation landscape would be greatly benefited by having younger faces (ideally women, people of color, people with compelling backstories involving climate impacts) with fresh ideas.”

But the purists also contend that Gore’s message just isn’t strong enough. At least a third of An Inconvenient Sequel, for instance, was devoted to the Paris agreement, which many activists see as inadequate to address climate change. Most scientific analyses have found that even if every country keeps its commitments, the atmosphere would still warm by 3 degrees Celsius—an improvement over the worst-case scenario and the status quo, but not enough to prevent irreversible consequences for millions of people. “I’d probably walk out if the movie celebrates the Paris climate agreement,” Rogers-Wright, said. The movie does exactly that: Gore calls the agreement “a new chapter of hope for the world.”

But Gore also has plenty of defenders who are willing to go to bat for him. “Yes it’s true that many people may have formed an opinion about Al Gore. It’s also true that sometimes people can surprise you,” Brune, of the Sierra Club, said. “I give conservatives and independents more credit than that. I think they may be able to hear something from a well-known person—even a person they don’t like very much, they may be willing to change their assumptions.” RL Miller, the president of Climate Hawks Vote, made a point that even Gore’s detractors must concede as true: “Sure, you can point to fresher voices, but you cannot point to anyone who has as much international recognition, or heft, or star power as he does.”

The criticisms of Gore, while sometimes legitimate, are so numerous and impassioned as to reveal something deeper at work: an anxiety about the direction and effectiveness of the movement itself. There’s a profound fear among many activists that time is running out, that we have only a few more years to take the necessary actions to solve the climate crisis. Now here comes Gore, one of the most powerful figures in the climate movement. Perhaps more than anyone, he has the celebrity, the connections, and the resources to influence where it goes from here. What if, simply put, he blows it? It’s an understandable concern—and no matter what decisions he makes, he’s sure to upset one camp or another. But one thing’s for sure: Gore isn’t going away anytime soon. “I feel very deeply about what the right thing is,” he said in An Inconvenient Sequel. “I’m not confused about it at all.” Such confidence isn’t likely to mollify his critics, but it should give hope to a movement that is itself confused about where to go from here. After all, if Al Gore has the power to mess everything up, maybe he also has the power to solve the whole damn thing.