“I have a natural horror of letting people see how my mind works,”

a 23-year-old John Ashbery wrote to the painter Jane Freilicher in 1950. It’s

not a surprising sentiment. Ashbery, who will turn 90 at the end of this month,

has always been a notoriously elusive poet. His work combines a tone of

intimacy and revelation with an intractable obscurity: It is just forthcoming

enough to make you realize how much is held back.

Though Ashbery has been both prolific and public over the course of his long career, publishing more than thirty books and making himself available for readings, interviews, and workshops, he’s still retained an air of mystery and a penchant for privacy. For the most part, he’s shown indifference toward the scholarly apparatus that’s been gradually building up around his work for decades. A certain suspicion of explanation, particularly biographical explanation, has been at the core of his aesthetic. As he summed it up in his 1972 essay “The Invisible Avant-Garde,” the closest he’s ever come to a personal manifesto: “To create a work of art that the critic cannot even talk about ought to be the artist’s chief concern.”

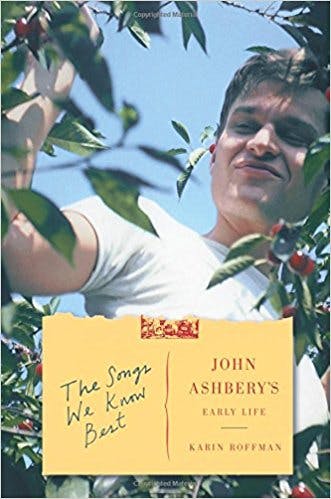

The appearance of Karin Roffman’s The Songs We Know Best: John Ashbery’s Early Life, the first biography of Ashbery, thus comes as a slight surprise. In a brief preface Roffman makes clear that Ashbery participated fully in the project, granting her numerous interviews over the course of nearly a decade and making available private documents, including diaries he kept between the ages of 13 and 16. The book’s scope is limited, covering only the first 27 years of Ashbery’s life, up to 1955, when his first collection Some Trees was published and he departed for France on a Fulbright. But it is by far the most thorough and reliable account of a formative period in the biography of one of our greatest and most mysterious writers.

Born

in 1927 in Rochester, New York, Ashbery spent his childhood shuttling between

nearby Sodus, where his father owned a fruit farm, and the even tinier village

of Pultneyville, where his maternal grandparents lived. From a young age, he felt

like an outsider in this rural environment. Poorly suited to work on the family

farm, he retreated into the dream worlds provided by books and movies. His

sexuality contributed to his sense of isolation. Ashbery was attracted to boys from the time he was in kindergarten, and

anxieties about his homosexuality and its possible discovery were a constant

feature of his childhood and adolescence. He made only careful, coded

references to homosexuality in his journals and letters, which Roffman has patiently

deciphered with the help of the author himself.

After an early sexual experience in 1941, when he ejaculated for

the first time after fooling around with a male friend during a sleepover,

Ashbery jotted a “poem-note” in his diary “made up of phrases from their

conversations that he did not want to forget”:

tulip garden

old dutch

home all our own until

recall once more

fashion in shows

dog cast in

days before

were almost learning to forget

happy fear came from

a trough

kin

It’s remarkable how closely this fragmented, unsyntactical text, written when Ashbery was thirteen and had yet to encounter any modernist poetry, resembles his avant-garde experiments with verbal collage in The Tennis Court Oath and other books. Compare, for instance, this excerpt from “Europe,” written two decades later when Ashbery was living in Paris at the epicenter of the global avant-garde:

songs like

You came back to me

you were wrong about the gravestone

that nettles hide quietly

The son is not ours.

Roffman argues, plausibly, that Ashbery’s practical need to disguise his homosexuality led him to cultivate his taste for ambiguity and indirection, and she analyzes many of his early poems along these lines. This way of understanding Ashbery’s cryptic aesthetic isn’t new—it’s been around since at least 1994, when John Shoptaw’s On the Outside Looking Out argued for a “homotextual” interpretation of his work—but Roffman opens up a whole new archive of powerful biographical evidence supporting it.

She finds other auguries of Ashberyness too, like a play called Twelve Nights in a Barroom he wrote, at the age of fourteen, over the course of a series of letters to his friend Mary Wellington. “Since Mary had the only copy of a previous scene, John could never remember title, characters’ names, or plot from one letter to the next, a situation he exploited for comic effect,” Roffman writes. “This exaggerated forgetfulness exempted him from any responsibility to continue the plot from exactly the point at which he last left off the story. As the work developed, he also shifted its genre from horror to mystery, to melodrama, to romance, adroitly exaggerating these frequent shifts in tone.” As anyone who’s tried to track the “plot” of an Ashbery poem knows, this sense of narrative “responsibility” has rarely returned.

The most significant event of Ashbery’s early years was the sudden death of his younger brother, Richard, from leukemia in 1940, when Richard was nine and John was almost thirteen. Ashbery’s parents shielded him from most of the facts of his brother’s illness, and it came as a shock to him when he was informed that Richard had died. While the brothers were never especially close, Richard’s death seems to have cemented John’s sense of himself as a solitary, melancholy individual at the mercy of a capricious universe. Ashbery’s 2000 poem “The History of My Life,” quoted by Roffman, gives a sense of the idiosyncratic way he processed the tragedy:

Once upon a time there were two brothers.

Then there was only one: myself.

I grew up fast, before learning to drive,

Even. There was I: a stinking adult.

The note Ashbery strikes is not one of grief, but of bafflement: The suddenness of Richard’s death is linked to the suddenness of adulthood; both are examples of the way things can change irrevocably. (The mock-poetical inversion “There was I,” a typically goofy touch, contributes to the sense of passivity, by making “there,” as opposed to “I,” the subject of the sentence.)

The narrators of Ashbery’s poems typically present themselves as more or less average people living more or less average lives (with “thoughts and ideas,” in this case, “at least as good as the next man’s”) who are always at the universe’s mercy: a brother can disappear without warning, or “a great devouring cloud” can come and “loiter,” obliterating the “horizon” toward which that average life had been oriented. Such images of unexpected, unexplained change—often visualized as natural forces like clouds, storms, or waves—are common in Ashbery’s poetry. His protagonists (if that’s the word for them) are never far from having their worlds transformed.

Like all biographical accounts of the early years of famous writers, The Songs We Know Best has an archeological aspect, devoted to reconstructing detail by detail the edifice of a style. Ashbery wrote his first poem, “The Battle,” at the age of eight, inspired by a viewing of the 1935 film adaptation of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. It tells the story of a clash between an army of fairies and rabbits and an army of anthropomorphic bushes and trees. (Shades of Girls on the Run, Ashbery’s 1999 epic inspired by the art of Henry Darger.) “The Battle” was so well received by the author’s friends and family that he immediately came down with a case of writer’s block, unable to produce another poem for seven years.

As might be expected, Ashbery’s early poems show facility and talent, though it took quite a while for his distinctive manner to appear. They’re interesting, though, as a register of his literary influences. As a child he loved Tennyson, Shakespeare, and the Romantics; poems like “Miserere” (“Ah! Bleak and barren is the moor / The orphan girl she sheds a tear / And thinks of home, her parents dear / Departed from the worldly sphere / Full seven months ago!”) are firmly grounded in a conventional Victorian idiom that still rears its head from time to time in Ashbery’s work. Later, he discovered modernism via anthologies like Louis Untermeyer’s Modern American Poetry, Modern British Poetry, gravitating especially to H.D., Hart Crane, and Gertrude Stein. A poem like “To Rosa,” written in 1943, is a good example of his teenage style:

You came

To me like vines

Reaching up to strangle

An abandoned house with quiet

Sureness.

The poem is notable not only for the influence of Imagists like H.D. and Ezra Pound but for its being written in a set form: the cinquain, a five-line poem pioneered by the poet Adelaide Crapsey. A fondness for obscure or antique verse forms (sestinas, pantoums, centos, et cetera) would eventually become a hallmark of Ashbery’s writing, distinguishing him from contemporaries who preferred to abandon these old conventions in favor of postmodernist innovations like projective verse.

Ashbery’s career as a professional poet got off to a rocky start. Unbeknownst to him, two of his early poems ended up published in Poetry magazine under the name “Joel Michael Symington.” A high school classmate, Bill Haddock, had presented the poems to the poet David Morton, who in turn submitted them to Poetry; when they were accepted, Haddock tried to cover his tracks by inventing a pseudonym. Amazingly, Ashbery forgave Haddock, who went on to publish yet another of Ashbery’s poems—this time under his own name—in the little magazine Voices.

At Harvard, which he attended from 1945 to 1949, something like a recognizable Ashberyan canon of influences starts to cohere. He falls in love with W.H. Auden, Wallace Stevens, Marianne Moore, Marcel Proust, Henry James, and Ronald Firbank, and nurtures contrarian antipathies toward Eliot, Frost (“Something there is that doesn’t love Robert Frost,” he wrote in his lecture notes), and Robert Lowell. (Ashbery’s parody of Lowell’s turgid style—“Mudgulping trawler, Truro in the ooze / Past Peach’s Point, with tray of copper spoons / For Salem’s Mayer Caldecott to suck”—belongs alongside Frank O’Hara’s acid commentary on Lowell’s “Skunk Hour” in the pantheon of sick poet-on-poet burns.) Already the contours of what Ashbery would eventually term “the other tradition”—defined, like all traditions, by what it eschews as well as what it includes—are becoming visible.

It was at Harvard, too, that Ashbery met many of the friends that would make up his post-collegiate literary coterie: O’Hara, whom he called his “identical twin”; Kenneth Koch, who encouraged him to apply for a position on the editorial board of the Harvard Advocate, despite their unenforced policy against homosexuals; and Bubsy Zimmerman, later known as Barbara Epstein, one of the founding editors of the New York Review of Books, who had a hopeless unrequited crush on Ashbery. After college they all gravitated to New York City, where they cross-pollinated with the groups around the Abstract Expressionist painters, the Living Theatre, and other assorted avant-gardes.

The social entanglements of the various members of the so-called “New York School” are legendary, but Roffman wisely avoids getting bogged down in too much detail about who drank or slept or collaborated with who—matters that, given the tendency toward gossip of the parties involved, are uncommonly well documented. (For those who are interested, David Lehman’s The Last Avant-Garde and Brad Gooch’s biography of O’Hara are good places to start.) She does, however, devote considerable space to the wrangling over Ashbery’s first book, Some Trees, which W.H. Auden selected, over O’Hara’s Meditations in an Emergency, for the Yale Younger Poets prize in 1955. Auden was actually rather ambivalent about the manuscript, which was somewhat too surrealist for his taste, and made Ashbery excise poems that included the words “masturbation” and “farting”—though he left in the line “the sun pissed on a rock,” which survived to scandalize the poet’s mother.

A writer like Ashbery is, in one way, a scholar’s dream. His work is full of cross-references to be tracked down and mysteries to be decoded, and it is in consistent dialogue with both its contemporary historical moment and with the literary canon (however eccentrically that canon is defined). On the other hand, a sense of privacy and inscrutability is intrinsic to the experience of reading him: An Ashbery whose work had been fully explicated wouldn’t be Ashbery at all. The Songs We Know Best lets us see, clearer than ever before, how the poet’s mind works, and how it developed. Still, you can’t help remaining a little nostalgic for the mystery.