It’s rare, though not impossible, to connect emotionally with one of Haruki Murakami’s characters. They are transparent nonentities, serving to focus and magnify. Think of Aomame from 1Q84, who floats through a slightly shifted alternate world, observing but largely apart from it. The nameless narrator of Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World cooly scrutinizes a bizarre world inside his own mind. Like Emerson’s transparent eyeball, they serve as a lens for the peculiarities that surround them: They’re impressionable and neutral at the same time.

These viewpoint characters are usually men, because for Murakami, and for the audience he imagines—that is, for the audience that most male writers imagine—male characters are the most transparent. This isn’t a criticism of Murakami so much as an observation of the literary culture we’re all working with: Femaleness is seen as an additional ingredient, something extra and inessential to the real condition of humanity. The clearest lens is male.

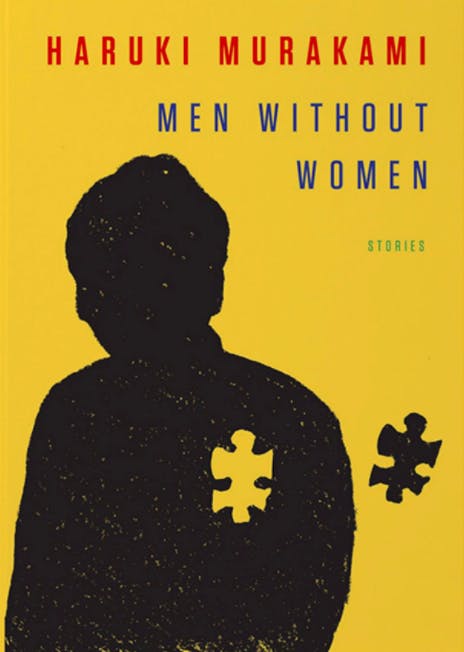

So it’s unsurprising that, of the seven short stories in Murakami’s new collection, all are fronted by men. It’s slightly more surprising—cheeky, even—that the collection is called Men Without Women. Is it a reference to the Hemingway collection of the same name? Is it daring the diversity-minded reader to object to the lack of female voices by making that absence part of its identity? The protagonists seem to define themselves in opposition to the women around them: An actor in need of a chauffeur expounds at length on why he doesn’t like women drivers; a plastic surgeon becomes so obsessed with his ideal woman that he wastes away. The collection takes its name from the final story, in which the narrator, having learned of the death of a former girlfriend, defines the phrase: “It’s quite easy to become Men Without Women. You love a woman deeply, and then she goes off somewhere. That’s all it takes.”

But what does “without” mean, exactly? The narrator of “Men Without Women,” the one whose ex-girlfriend is dead, learns the news while lying in bed next to his wife. Yet he goes on to define his experience as a man without women for the next dozen or so pages. The men in Men Without Women are in fact surrounded by women. Wives, girlfriends, friends, coworkers, mothers: Women are their atmosphere. A more accurate title might be Men With Loneliness. It’s not really about the women; it’s about the without-ness, using male characters as a lens to examine lack. In these seven stories, Murakami’s heroes look at the negative space of the other people (usually, though not always, women) in their lives—and find that what’s there disappears faster than it can be understood.

Men Without Women is best when it engages directly with its heroes’ alienation, their estrangement not only from women but from themselves. In “Scheherezade,” a man who is homebound for obscure reasons is visited regularly by a woman who provides him with groceries, sex, and personal revelations; the main character is both physically and emotionally cut off from the world, and his caretaker matches him loneliness for loneliness. She tells him stories about her solitary teenage crimes and her past life as a lamprey—a jawless, vampire-like fish. “Samsa in Love” reverses “The Metamorphosis” to bring us a re-transformed Gregor, disoriented and trying to learn again what it means to be human. And “Kino,” by far the strongest, is the story of a man who worries that his stoicism has made him vulnerable to malign magical snakes who want to make a home in his heart.

“ You were hurt, a little, weren’t you?” his wife had asked. “I’m human, after all. I was hurt,” he’d replied. But that wasn’t true. Half of it, at least, was a lie. I wasn’t hurt enough when I should have been, Kino admitted to himself. When I should have felt real pain, I stifled it. I didn’t want to take it on, so I avoided facing up to it. Which is why my heart is so empty now. The snakes have grabbed that spot and are trying to hide their coldly beating hearts there.

What would it look like for one of these men to feel real pain? We don’t really find out. By the end, Kino admits to himself that he’s been badly hurt, but it’s a confession the reader sees rather than feels. And whether it’s enough, whether it keeps the snakes away, we’ll never know.

Like Murakami’s novels, the best of these stories are beautifully, delicately unsatisfying. They shy away from resolution, leaving the reader suspended in midair. Some of the weaker offerings—“Yesterday,” “An Independent Organ,” and the titular “Men Without Women”—attempt a kind of coda in which the narrator reflects on events and tries to enact some form of closure. “Men Without Women,” in particular, is more coda than plot. The events of the story amount to a single phone call, and the rest is an attempt to wrap up the narrator’s feelings into something definite and knowable—qualities that Murakami has never been very good at pulling off. These attempts fail in every case. On the whole, the closing meditations in the stories tend to be stilted and ambivalent: “I hope that in Denver (or some other faraway town) Kitaru is happy,” writes the narrator of “Yesterday” about a lost friend. “If it’s too much to ask that he’s happy, I hope at least that today he has his health, and all his needs met. For no one knows what kind of dreams tomorrow will bring.” It’s a personal reflection, but one that rings as hollow as a yearbook signature. The unknowability of Murakami’s characters is most effective when it hints at the mysteries of our world, when it reminds us that everyone we meet contains so many depths and contradictions that we can never fully know them. But in the worst of these stories, we begin to suspect that Murakami’s men are unknowable only because they contain little worth knowing.

Those weaker stories also tend to be the ones that hew most closely to the idea of men without women: a man trying to escape the woman he’s been dating since childhood, a man who dies of a broken heart, a man forced to reckon with the death of a lover who left him a long time ago. The scenarios are straightforward and mundane, making the characters’ psychological isolation distancing, even off-putting. But Murakami’s greatest strength is his creation of environments just eccentric enough to wrong-foot you—not exactly magical realism, but perhaps enigmatic realism. Magic has its own logic; one doesn’t so much suspend disbelief as exchange one set of beliefs for another. But enigmatic realism requires not only the suspension of disbelief but the suspension of expectation—the expectation that one event will follow from another, that scenes and details will have some kind of logical or symbolic relationship, that the reader can recognize characters as people she could reasonably expect to meet. This is a lot to ask a reader to accept, and it’s only a worthwhile investment of effort when the result approaches the transcendent. Transcendence is not a goal served by the pat conclusions that mar some of these stories.

It’s only when surrounded by light surrealism that the characteristic Murakami detachment can achieve its ambition. When his writing is at its best, his characters act as a fisheye lens through which to scrutinize a slightly off-kilter world that surrounds them. The soft armor of their unknowability lets us examine their loneliness up close while still feeling far away.

Do we really need another book about men without women? I’d say that the answer is no. Even leaving Hemingway aside, at least half the literary canon is about men without women already. But stories about loneliness, about estrangement, about lack: There our appetite is endless, and Murakami offers up a new and striking way to feed it. Where Men Without Women tries to make a statement about, specifically, men and women, it fails: too self-conscious, too glib. But for people intrigued by the many facets of loss, the rest of the collection offers classic Murakami—refreshing, unusual, lustrous, with a vacancy at its heart.