Broadly speaking, the United Kingdom is not a rich country. It is an economically average country with one exceptionally rich region. Of the 15 strongest economies in the European Union, none are as dependent on one area—London—as the U.K. Among the top ten richest regions in Northern Europe, a stretch that includes France, Germany, Belgium, Holland, and the Nordic countries, London is the U.K.’s only representative. But of this area’s ten poorest regions, the U.K. accounts for a remarkable nine.

London’s per capita GDP is almost two-thirds higher than the U.K. average, and almost two and a half times higher than that of the U.K.’s poorest region, Wales. Alongside nearby Cornwall, Wales is the sole area in Northern Europe to be categorized as a “less developed region” by the European Union—those with a per capita GDP less than 75 percent the EU average. This puts Wales in the company of parts of Portugal, northern Italy, and most of Eastern Europe. It also secures it—or secured it—the highest level of EU subsidies, receiving hundreds of millions of euros in funding for regional growth and regeneration schemes.

It came as some surprise, then, that when Britain’s membership in the EU was put to a referendum last June, Wales voted to leave the EU by 53 to 47 percent.

Nowhere was the vote closer than in the industrial valleys of Swansea Bay, an area on the Atlantic coast to the west of the Welsh capital, Cardiff. This region tells the story of both last year’s referendum and this week’s election.

The same issues are playing out here as in many parts of the West, whether the American Midwest or north of France: the fate of industry, changing demographics, a new thirst for nationalism. In Swansea Bay these ideas are thrown into relief by the constant, churning presence of what was once the largest steelworks in Europe, and is now one of the last major industrial sites in the U.K.

The Port Talbot Steelworks has been in operation for more than a century. It lies to the east of the bay, in sight of the small city of Swansea. Last year it appeared to be on the verge of closure, another tale of heavy industry fleeing Western shores, but after six months of being put up for sale by the Indian multinational conglomerate Tata, the plant’s latest foreign owner, its future was tentatively secured in November, with the company making a five to ten year commitment. It is estimated that more than a tenth of Port Talbot’s men are employed by the plant, and its economic impact is far greater than that.

Bill, 70, is one of those who long worked in the steelworks. “I was about 18 when I went in,” he says, as if were a rite of passage, sitting on a patch of grass with a pair of shepherd dogs on the otherwise barren promenade near the steelworks. His stepson works “inside” now. The blast furnace he works on is due for relining, but no one expects Tata to carry out the refurbishment. “It’s quietly going,” Bill says. “I wouldn’t give it five years.”

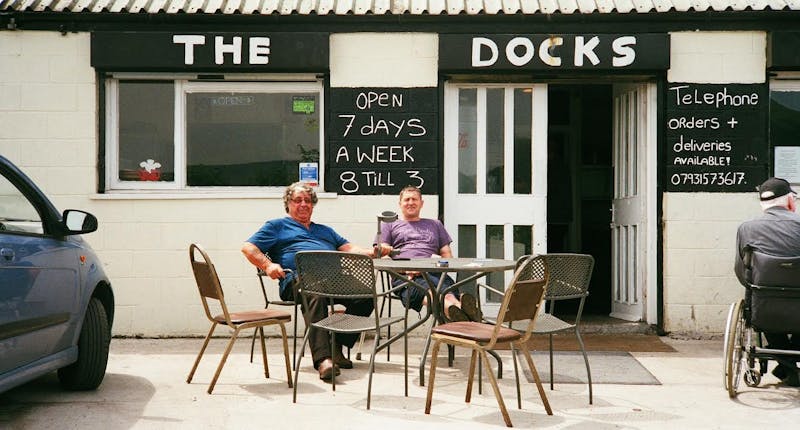

Derrick, 57, heavily tattooed and built like a short tank, tells a different story. He also did his time in the plant, like his father and brother. But his perspective on the steelworks is shaped by his being the co-owner of the Docks Cafe, a low-slung hideout of a place, tucked away down an unmarked road in the shadow of the plant.

On Sunday at lunchtime it is unexpectedly alive, full of both customers and cars arriving to collect orders. The three women at work have no time to talk. The narrative typically spun about south Wales—beautiful valleys filled with boarded-up shops—could not be less relevant here.

Business is “lovely, lovely,” confirms Derrick. “That,” he says, nodding to the steelworks, “is the lifeblood of Port Talbot.” In his telling, the steelworks “hasn’t come down as far as manpower is concerned, there’s still 30,000 men working in there, who still live in the area.”

What has changed is the type of employment. The well-pensioned steelworker has been replaced by the contracted employee. The foreign conglomerate du jour benefits and the area stays alive, but the town’s bulwark now rests on softer ground.

All of this gives the conglomerate the upper hand. Derrick thinks Tata was never going to shut down the steelworks last year. It was playing poker with the British government, forcing it to support Tata’s investments and accept its energy prices. Meanwhile, experts from around the world were secretly arriving at the plant, tasked with figuring out how Tata can drill through the coal-filled mountains nearby and create its own electricity.

A more transient workforce. Government largesse. An independent energy supply. It all adds up to more money for Tata, while it publicly proclaims that it is “still a long way” from securing the plant’s future. The machinations of modern capitalism are so murky that most people—employees, journalists, politicians—are often left wondering not just what will happen, but what game is even being played.

Naturally, the two major parties in this year’s election—Conservative and Labour – are not discussing these issues in much depth. The complexities of capitalism are not on the nightly news. As they did two years ago, the Conservatives have boiled their message down to security, foreign and domestic. Led by Prime Minister Theresa May, they claim that Labour’s left-wing leader, Jeremy Corbyn, is a national threat. Only a “strong and stable” Tory government can deliver Brexit.

Traditionally, the Conservatives have been the party of business, and Labour the party of, well, labor. It was out of the coal-mining valleys of South Wales that Labour became a national force. Its founding father, Keir Hardie, for 15 years represented Merthyr Tydfil, a coal-mining town 20 miles inland from Port Talbot. A generation later, Nye Bevan, a coal miner’s son from nearby Ebbw Vale, was the minister responsible for creating the National Health Service after the Second World War.

According to Kevin, 66, a friend of Derrick’s who drives down from the Valleys to the Docks Cafe every Sunday, Labour’s long-standing support here had a simple basis: Labour politicians “kept coal-mining owners getting payouts.” In the 1980s those payments stopped when Margaret Thatcher forced the closure of coal mines across the U.K., a decision that many say devastated Wales.

But Kevin and Derrick tell another tale. “That’s the only good thing Thatcher ever did: Shut the pits,” they say in unison. “The valleys have come back to life,” Kevin continues. “Instead of being full of coal muck and coal dust, when you wasn’t able to hang your washing up on the line, now we’ve got beavers, we got trout back in the rivers. People got a happier life. You won’t believe it off the ex-miners though, they say, ‘Noooooo, ruined our life.’ Well you go look how many ex-miners got bloody Jags parked outside their house.”

It is not the story typically told. When one reporter visited the region a few years ago, he wrote a piece so pessimistic it included the remarkable line, “Even weeds don’t grow here.” In Kevin and Derrick’s account, the legacy of deindustrialization has been far less severe—thanks to the pensions that mine workers were able to secure. This is one of the major questions Port Talbot faces today: Should the steelworks shut, will its increasingly subcontracted workforce have pensions on which they can survive?

Bill is skeptical. After Tata’s brinkmanship last year, he thinks they have all but “got rid of the pensions. “Now they can do what they like.” In his eyes, this is the result of the process Thatcher began: “She took this country to the brink of extinction.” Bill is a lifelong Labour voter—and “I’ll do it again this year”, he says defiantly. He has his reservations about Corbyn, particularly on national security, but insists, “You’re not voting for him, you’re voting for the party.” Theresa May, he says, “will be worse that Thatcher.”

Derrick sees things differently. “I’ll be voting for the Iron Lady,” he says, giving May the moniker that she is so eager to adopt from Thatcher. Still, he is critical of Thatcher, saying, “I know she wasn’t so good for the country cause she privatized everything, and destroyed a lot, which we should be taking back: trains, the post office, steelworks. All that, all proper British industry.”

Corbyn is the candidate who wants to renationalize some of these industries, but Derrick considers him “a lunatic” who wants to scrap Britain’s nuclear arsenal. “He’ll leave us open to more attacks.” And May has won his vote over Brexit, which he voted for last year. “We are not getting a quarter back of what we are putting in, as you well know,” he declares emphatically (and erroneously). His talk turns to trade, and he almost makes a Trumpian slip. “Make Britain … get Britain … back … trading with the world.”

When pressed, the darker side of his nationalism comes out. “We’ve got to stop all these people coming to this country,” he continues. “This is what everybody’s not saying. Brexit … It’s all about the Arabs, the terrorists.” He points to the Manchester Arena attack. “This is a knock-on effect isn’t it, because we poked our noses in. If we’d left Saddam and Qaddafi alone, they’d be none of this.” And then paints an alarming picture of “body builders” and “special forces” arriving at Southampton Docks “with caches of arms everywhere.”

Bill agrees with Derrick on one front: leaving the EU. “It wasn’t a fair share,” he agrees. “As far as I was concerned it was run by Merkel and the French president.” When asked about the subsidies paid to Wales, neither understands why they are necessary. “Why have the farmers got to live on subsidies?” Bill asks. “They’ve done all right before we went in there.”

Voters like Bill—those who vote Labour but backed Brexit—are now oddly placed in British politics. It is estimated that 60 percent of Conservative voters backed Brexit, compared to 35 to 40 percent of Labour voters. Which makes “Labour leavers” like Bill a minority within their own party—a party led by a candidate in Corbyn who campaigned against leaving the EU but who is now committed to doing so. Theresa May—who also thought Britain should stay, but mainly avoided saying anything at all during last year’s campaign—is promising voters like Bill a decisive exit from Europe. And while she has not swayed Bill, a key question this week is whether she can persuade those like him.

Shortly after May announced the election six weeks ago, shock polls suggested the Tories had made major inroads with such voters. They showed the Tories beating Labour across Wales, which they haven’t done since 1922; they have not won the most seats here since 1851. “For once, words like ‘sensational’ and ‘unprecedented’ do not seem out of place,” one pollster said. Theresa May even travelled to Wales to make a speech. “This election is not about calling in old favors or relying on past allegiances,” she declared.

More recent polls have shown Labour faring better, but support for the party has been slipping for years. In 2001, they beat the Conservatives by 49 to 21 percent. Two years ago their margin was down to 10 points: 37 to 27 percent.

Last year’s referendum cut across party lines and realigned British politics in ways that are not yet clear. This week’s vote will begin to offer answers. Theresa May and the Conservatives are expected to win the election. The question nationally is: “How close can Labour come to the Conservatives?” But the question in Wales is: “How close can the Conservatives come to Labour?”

Labour is likely to hang onto its ascendancy for now. But the party is searching for an identity in a way that the Conservatives—the party of money, of privatization, of nationalism—are not. In an economy where more than 80 percent of jobs are now in the service sector, it is not clear what being the party of “labor” still means. Call centers and supermarkets do not create the same kind of politics as coal mines, and traditional heartlands have slowly turned into crucial battlegrounds.

Port Talbot itself remains a safe Labour seat for now, and is held by the son of a former Labour leader. But on the other side of the Swansea Bay, in the richer, rural peninsula of Gower, is the site of the most fiercely contested seat in the country. Two years ago the Tories won the seat for the first time in 109 years, by 27 votes after two recounts. Last year it voted for Brexit by 50.1 to 49.9 percent.

The Port Talbot Steelworks are visible from the eastern edge of the Gower, along its promenade—café-lined and far busier than Port Talbot’s. If Talbot represents Wales’s industrial past, the Gower looks much more like its future: French and Italian restaurants, American coffee chains. But the two sides of the bay could yet be united by a project that has been in the works for ten years: a tidal system stretching across the bay that will create renewable energy.

Kevin and Derrick are excited by the idea. “It’s absolutely fantastic,” says Derrick, with a hint of pride. “It’s making energy as the tide comes in and it’s making energy as the tide goes out.” Corbyn has committed to the project if elected, while May has, as ever, offered a more hesitant assurance. If approved, it could be a new source of industry and life for the region after the decades of coal and steel.

Britain’s exit from the European Union, and the impact it could have on either subsidies locally or government finances nationally, could yet scuttle the plans. And Kevin, who is yet to decide how he’ll vote this week, is apprehensive. “I’ll be quite honest with you,” he says softly, “I don’t think we should have come out of Europe. Sterling has already dropped 13 percent against the dollar in the past few weeks. Wait till we come out …”

“And it’ll fly up,” Derrick interjects. “You wait until the trade deals come in,” he quips. “I won’t be having a foreign car then will I?”