Art loves a landscape. The past is full of landscape painting, and pastoral poetry, and stories about magical trees and enchanted roses, and the rolling hills of folklore. But to say that a work of art is about landscape does not mean that it merely depicts trees or grass. A landscape is a spectacle, perceived and interpreted by the human eye. A landscape is a space with a frame around it, planted like a garden full of meaning.

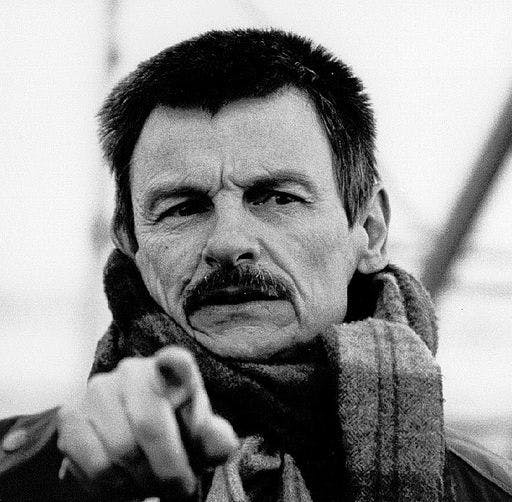

Andrei Tarkovksy’s Stalker (1979) is a landscape movie. It has just been restored, and a more brightly colored, brilliant version of itself is showing in New York. In July, the restoration will join the Criterion collection on Blu-Ray, gussied up with a Geoff Dyer interview and various other tidbits.

Stalker is technically an adaption of the 1971 novel Roadside Picnic by Boris and Arkady Strugatsky. But that book is fairly orthodox science fiction about aliens, not the highly ambiguous dreamscape that Tarkovsky ended up filming. The movie’s initial reception was not warm. Upon hearing from officials at the USSR’s State Committee for Cinematography that the movie was too slow, too grinding, Tarkovsky responded that, rather, it needed “to be slower and duller at the start so that the viewers who walked into the wrong theater have time to leave before the main action starts.”

New York always whispers about Tarkovsky, since he is a hero to the kind of film nerd who gravitates toward lonely dystopias full of rats. But with the pitch of Tarkovsky conversation at a high, and the administration’s climate policy pitching at a historic low, the time has come to give Stalker its due as the great apocalyptic opus for the climate change era.

The first few scenes of Stalker are urban ones, shot in sepia. A man referred to only as the Stalker meets two men, named the Writer and the Professor, in a monochrome world. He promises to guide them into a place called the Zone, which the government has sealed off.

The group takes a speeder out of town, which is one of those railway cars you propel by pumping a handle. The Zone is in color, and neither its precise characteristics nor the reasons for its existence are clear. It contains ruins, a dog, flowing water, many trees. There are dangers involved in crossing the Zone’s terrain. A traveller must never take the same route twice. The Stalker tests the safety of the route by throwing little metal nuts knotted with rags ahead of the group before they move. He is the only one who can sense his way through the unnamed violence of the landscape, the only one who can take them to the Room.

For the gang seeks a chamber within the ruin that will grant the deepest desires of its visitors. But just as that desire has made each visitor suffer, true fulfillment will do the same. The Stalker refers to another guide from the past named Porcupine, whose conscious desires were trumped by unconscious ones: The Room gave him all that he did not know that he wished for, and destroyed his life. The Professor and the Writer seek the Room for very different reasons, and the Stalker’s own connection to the Room is unclear. Inside, birds appear from nowhere.

Stalker’s greatness lies in the journey. Tarkovsky makes a drama out of walking through a field that appears to contain no threats as we usually conceive of them. There is just grass and a hum of terror in the air. We hear breezes but do not see the branches moving. The rivers and fires and drips that we can see do not match up to the soundtrack (we cannot hear the huge waterfall until it is right in the middle of the screen).

Space is political, in the real world. People fight over territory at every level: Neighbors bicker over the property line, while borders define the shape of every nation and pin their identity to the map. The Zone of Stalker takes place right on the line that divides here from there. It is overgrown the same way that the Demilitarized Zone is overgrown, that strip of land between North and South Korea that is like a geographic scar. It is abandoned the way that the area around Chernobyl is abandoned. The science fiction author Bruce Sterling calls spaces like these “involuntary parks.”

Sterling’s vision is tied both to politics and to sea levels rising due to climate change. He imagines spaces that look like national parks, “those government-owned areas nervously guarded by well-indoctrinated forest rangers in formal charge of Our Natural Heritage.” But the new system of involuntary parks will not be “natural,” at least not in the way that we understand that concept. He sees drowned cities, seeping saltwater, kudzu and bamboo and violent animals.

These visions underscore the urgency of Tarkovsky’s Zone. President Donald Trump has wrenched the United States out of the Paris Climate Agreement, and in other ways has brought us that much closer to catastrophic climate change. We should look around us and see a Zone coming into being, the spread of those toxic, forbidden regions now guarded by nation-states.

The clock ticks. Tarkovsky’s Zone of liminal danger threatens to inherit the earth. Art about landscape will never be what it used to be, because our frame has changed. What better time to acquaint ourselves with Tarkosvky’s vision, brighter and clearer than ever?