In early modern Europe, women of certain classes were allowed to leave their salons only to eat, sleep, and go to chapel. “Beware what women do in gardens, arbors and bowers, banqueting houses, galleries, turrets,” one manual published in sixteenth-century England put it. “They may (and doubtless do) many of them play the filthy person there.” The warning was clear: keep women out of public, or God knows what they might do.

The stakes for women’s free movement became higher after the 18th century when nascent democracies were shaped in public forums. In Paris, with the new avant-garde of Romanticism, art shifted away from epic tales of gods and kings towards representations of everyday life in the city. Walter Benjamin would note in his theory of “panoramic literature” the recurring effort to capture a snapshot of the space and inhabitants of a city, as an effort of self-understanding in the face of perceived chaos. The height of this effort came with an explosion of publications in the early nineteenth century written by and for flâneurs, happenstance and idle wanderers of the streets. Implicit in this cultural development was the constitution of a radical subjectivity experienced at the level of the individual. The flâneur was a purposefully dysfunctional member of society, refusing to join the forces of productive labor, whether in the factory or in the academy, claiming his own importance as a perceiving subject rather than by class or profession. But for much of its history, the flâneur was exclusively male.

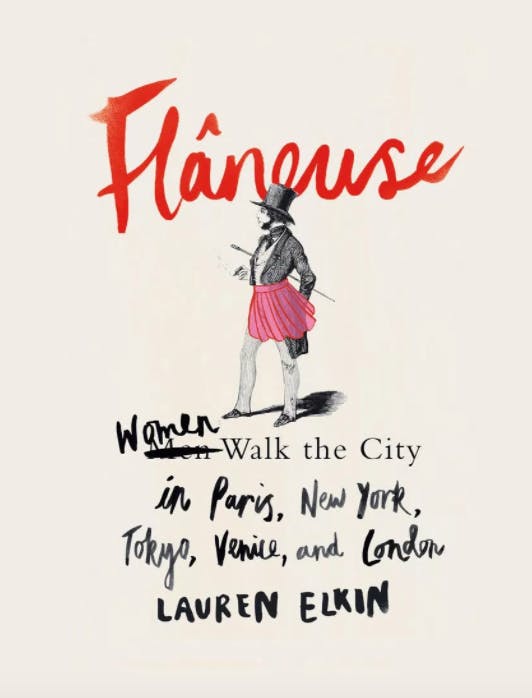

In Flâneuse: Women Walk the City in Paris, New York, Tokyo, Venice and London, Lauren Elkin asks what happens when the word takes on its feminine variant. In doing so, she contests years of feminist scholarship claiming the impossibility of such a woman wanderer of the streets. According to everyone from Griselda Pollock to Janet Wolff, women’s societal and marital “duties” trapped them inside. As soon as they stepped out of doors they put themselves on visual display as flesh for hire—just think of the connotations of the words tramp, streetwalker—or risked the humiliation of street harassment. The idea was that when a women went out in public, she was there to be looked at, rather than to look. Elkin challenges this version of the story by taking the reader on a tour of Paris, New York, Venice, Tokyo, and London, all cities she’s lived in, devoting each chapter to a certain historical moment in the city, an artist or writer who lived there at the time, and the way her own life has intersected with the monuments and books these people—women, mostly—left behind.

In London we follow Virginia Woolf as she prowls through Holborn and Bloomsbury at the gloaming hour, an act necessary for her art: “Crowded streets are the only places, too, that ever make me what-in-the-case of another-one-might-call think.” Two chapters are devoted to George Sand, and Elkin deconstructs the version of her life readers of English tend to be familiar with, the cross-dressing and cigars and multiple love affairs with famous artists, instead giving us a portrait of a woman who must climb up stairs and make a living in a society that insists she needs a man to do so. When she puts on her breeches, the disguise allows for freedom through anonymity: “I was an atom lost in that immense crowd,” she says. Elkin imagines Sand “tossing her little velvet hat on the floor and stamping at it, growling and swearing.” It’s a vision that adds complication and humanity to an often simplified figure: rather than adopting pants just because she wanted to break the rules, Elken shows Sand living out the frustrations of objects in their awkwardness, determining on her own which free her, and which constrain.

When Elkin herself goes to find material for her first novel in Venice, we come to know the city through the eyes of the artist Sophie Calle. Calle once travelled to Venice in pursuit of a mysterious man, “Henri B.” Calle’s story reverses the usual roles of man as voyeur and woman as passerby: Elken shows us Calle’s fascination with Henri, how she follows him from a distance, dodging in and out of shops to watch while remaining out of sight. Later, a chapter devoted to Agnès Varda’s Cléo de 5 à 7 furthers this exploration of the female gaze. The film follows Cléo, a pop singer who walks around Paris while waiting for the results of a medical exam. Cléo suspects that she’s dying of cancer; in the film, it’s implied that her illness may be imaginary. But over the course of the film she finds self-possession, even calm, as an observing subject of the world. Cléo seems most in control when she herself is not in the frame, in moments when the camera’s gaze shows us what she sees. It’s a marked difference from the kaleidoscope of mirrors at the beginning of the film, in which her many reflections serve as a series of dead ends.

A biblio-memoir, Flâneuse is marked by Elkin’s experience as a reader, writer, and wanderer of the streets in her own right. In reclaiming the city streets as liberators rather than oppressors of women, Elkin shows that inhabiting a space can be the means of asserting a voice and an identity. She no longer needs to “haunt” streets, the strangely spectral metaphor used by Virginia Woolf. She can fully inhabit them. Each chapter begins with a walk as a sort of compass, claiming an orientation and a position in space: “north on rue de Rennes, past the Fnac, Naf Naf, H&M, right at St Placide and north-east on rue de Vaugirard, past the Institut Catholique where I once taught, keep an eye out for the lovely bookseller in an old butcher’s shop … ” The way she moves through thoughts and words—unhurried, luxuriating in commonplace detail, digressions and detours developing into the main point—seems to be the textual version of these strolls.

Elkin tries to modernize and feminize the flâneur by filling in the role herself. The dedication of this book has been given to Trivia, “goddess of crossroads,” and that perhaps purposefully describes the majority of autobiographical details included, following the trend of what the critic James Wood has described as a “radical transparency” of self. Yet it is striking that rather than being the portrait of an artist as a young woman, Elkin’s journey of self-realization ends up being defined by romance. Paris seems to be traced with the memories of her dating experiences; the fountain by the Comédie Française where she kissed someone, her flat that was on the Left Bank because her ex hated the Right. She often maps out her own position in the city by way of the men in her life. Women’s lives have often been shaped by men, of course, largely because they were linked to them for so many centuries by economic realities. Conspicuously, Elkin never explains how she could afford all this travel.

For a book that takes the transgressive participation in the public sphere as its subject matter, I couldn’t help but wonder why in the end it felt somehow tame, cautious even. This is perhaps the effect of the perception of the city as the premier subject, which actually enforces the gendering of space. Throughout the book, the suburbs, associated with the domestic and the women who keep house, are dismissed as unimportant and inconsequential, a place we grow out of in order to get a job and a life. Elkin describes one train ride on the Long Island Railroad as moving from Tudor façades (“if you can’t live in Tudor England, pretend you do”), to “pseudo-countryside,” to the “semi-detached pastel-colored house” and “anti-aesthetic of small suburban industry,” to, finally, the “art-deco sharp” and “majestic steel skyline” of New York. The city is masculine, full of gleaming, phallic skyscrapers, and to Elkin, this boys’ world is where the real action happens.

The idea that greater personal agency depends on the population density of your address needs to be problematized at the very least. The decentralized protest actions that have taken place in response to Trump’s election, for instance, are remarkable not only because of their turnout, but because they took place everywhere, suburbs included. Citizenship is not just about the city these days. Women showed up for the march in Mentone, Alabama, Skagway, Alaska, and Driggs, Idaho. The “Day Without a Woman” strike pointed to the significance of women’s experiences, no matter where they are, no matter how invisible. This event actualized the idea, long-theorized, that the private realm has political consequence: that the kitchen sink is just as important a terrain as whatever avenue one marches down. The most private of actions, far from the public space, all count in resistance against a patriarchy.

Flânerie is not dead. It remains integral to our conception of the writer functioning in the world as a sponge, taking in what she sees, hears, and smells. It’s just something we take for granted now, a banality rather than a radical political and aesthetic position. But that doesn’t mean that its potential is gone. By its very definition, flânerie necessitates that it must function as a response to the changes in the physical and social worlds. What happens when a woman goes on a walk, accompanied or alone? When she comes home and starts writing about what she has seen and what she has done, what she has been thinking about, and reading, and hoping, and dreaming all the while? That is for every woman to decide in the here and now.