Tom Perriello draws a Bernie crowd. At a town hall at the University of Mary Washington, bearded college kids in flannel buzz at the back of the room, while older voters in khakis and checked shirts occupy the folding chairs up front. They’re all eager to hear Perriello, who’s running for governor of Virginia, rail against the corrosive influence of money in politics, a political system rigged against workers—and, of course, the new president of the United States.

“Donald Trump ran the most viciously racist campaign of my lifetime,” Perriello says to applause, pacing back and forth in front of his audience like a hopped-up high school teacher. “This is our chance to keep Virginia as a firewall against that kind of hate and division.”

Before Trump’s election, no one expected Perriello—who left Congress in 2011 after serving a single term—to return to politics. Heading into November, the Democratic Party had a seemingly foolproof plan in place: Tim Kaine would be in the White House as Hillary Clinton’s vice president, and Ralph Northam, Virginia’s lieutenant governor, would take over the governor’s mansion from Terry McAuliffe. Much to Perriello’s dismay, Trump’s victory didn’t seem to alter the party’s thinking. “The day after the election, the entire political landscape changed,” he says. “But everyone in the establishment was scared and wanted to run the same playbook and act like nothing had changed.” So two weeks before Trump was sworn in, Perriello shocked party insiders by announcing that he would run against Northam for the Democratic nomination.

“The coronation was called off,” says Mark Rozell, a political scientist at George Mason University. “Many of the party establishment types were very surprised—and very annoyed.”

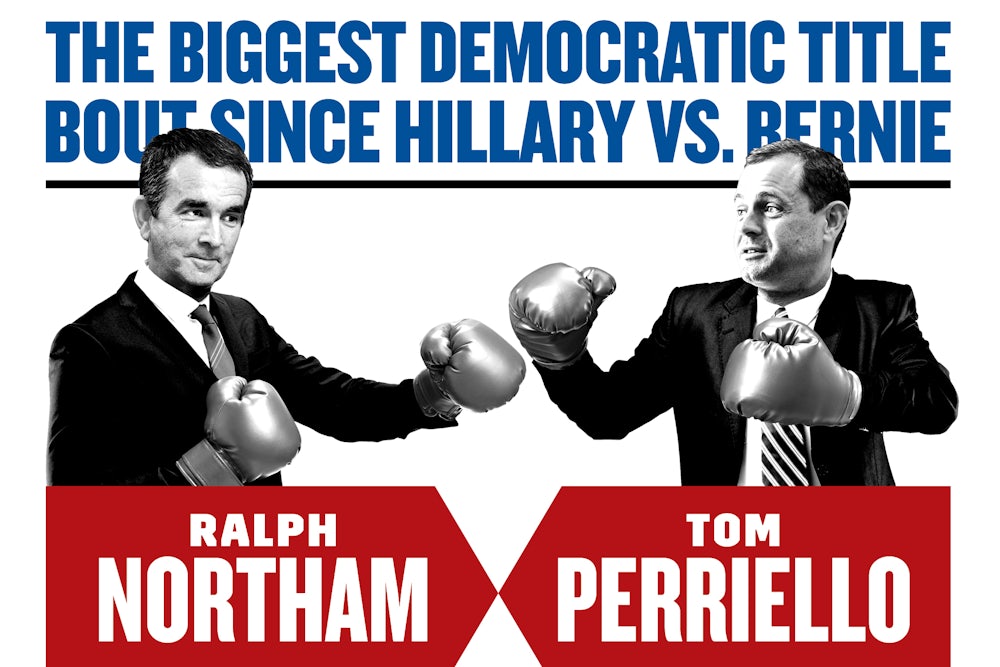

As the nation’s first election for a statewide office since Trump was elected, the June primary between Perriello and Northam will reverberate far beyond Virginia. In essence, it’s a Hillary versus Bernie rematch—the Democratic Party’s old guard squaring off against its younger, grassroots base. Northam is the reliable and cautious party stalwart: A former Army doctor, he speaks in a slow, deliberate drawl, is wooden on the stump, and carefully calibrates his message around proven talking points. An economic centrist, he sees little reason to overhaul a system that has brought jobs to the state. He even voted for George W. Bush—twice. (“Politically, there was no question, I was under-informed,” he says now.) But he has millions of dollars in his campaign war chest—crucial to a run in Virginia’s multiple media markets—and the endorsement of virtually every party heavyweight in the state, including Senator Kaine and Governor McAuliffe, the former chairman of the Democratic National Committee and the living embodiment of a Clinton insider. “The entire party apparatus is behind him,” says Quentin Kidd, a Virginia pollster and political scientist.

Perriello, by contrast, has made a name for himself as an energetic champion of social and economic justice who can connect with voters in both blue cities and rural red districts. In 2008, after nearly a decade as a human rights lawyer and peace negotiator in Darfur and Afghanistan, he overcame a 34-point deficit to unseat six-term Republican congressman Virgil Goode in a conservative southern district. In Congress, he was a staunch supporter of Obama’s agenda, voting for cap-and-trade, economic stimulus, and the Affordable Care Act. To sell Obamacare to his conservative constituents, he held more town halls in 2009 than any other congressman—and the following year he was rewarded as the only individual House candidate for whom the president campaigned. If he wins, it will be a major victory for the left wing of the party, which argues that the future lies not in cautious, Clintonesque triangulation, but in forceful, Sanders-like appeals for economic equality. “People are looking for a progressive fighter who can stand up and call Trump out for what he is,” Perriello says.

The party itself has been slow to adopt that view. After Trump’s victory, House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi blithely insisted that Democrats did not need to rethink their policies: “I don’t think people want a new direction,” she told Face the Nation. In February, Democrats selected Obama’s former labor secretary, Tom Perez, to serve as chairman of the DNC—beating out Representative Keith Ellison, a Sanders supporter who promised to put the party more in touch with its populist roots. But in recent weeks, emboldened by their initial victories over Trump’s travel ban and the Affordable Care Act, Democrats have gradually begun to embrace their role as the party of resistance. Even Perez acknowledges that the status quo isn’t working. “We have to rebuild our party,” he told Meet the Press. “We also have to redefine our mission.”

Virginia, however, didn’t get the memo. While the party hasn’t been open about its opposition to Perriello, he faces an uphill fight. Since announcing his candidacy, he has crisscrossed the state, appearing at anti-Trump protests like the one outside Dulles Airport in the hours after Trump’s immigration ban went into effect. He’s also been meeting with groups of Trump supporters every week, promoting his plans to revitalize rural communities and fight the opioid epidemic. He talks about the threat of automation to Virginia’s manufacturing jobs and the need for free higher education, and pitches a $15 minimum wage wherever he goes. When health care comes up, as it often does, he emphasizes his long-held support for a public option. “He’s the Bernie Sanders of the Virginia Democratic Party,” says Rozell, the political scientist.

Such stances have endeared Perriello to the Sanders wing of the party. Some of his most ardent supporters are young volunteers from Indivisible, which has emerged as perhaps the leading grassroots organization against Trump. Leah Greenberg, one of the group’s founders, worked for Perriello in Congress and served until recently as his policy director; Perriello officiated at her wedding. “It’s a situation where the energy within the Democratic electorate is on the progressive side,” says Kidd, the Virginia pollster. At a town hall in Manassas, one supporter hails Perriello as “not the chosen son of the establishment.” Another voices her disgust with politics as usual. “I’m sick of the Democratic Party,” she tells him. “But we’re with you!” In April, a town hall at the University of Virginia had to be moved mid-speech because so many college students showed up to hear Perriello that it violated the fire code.

Such grassroots support has enabled Perriello, like Sanders before him, to make up ground quickly. Despite entering the race nearly two years—and millions of dollars—behind Northam, Perriello was tied with his opponent by mid-February, and the candidates have remained in a dead heat ever since. In the first month of his campaign, Perriello raised more than $1.1 million, and he doubled that amount by the end of March. A Sanders-like 86 percent of his donations were $100 or less. It’s a sign “that Perriello is competitive—that this is a real race,” says Jennifer Duffy of the Cook Political Report.

It’s clear that the party establishment isn’t thrilled about Perriello’s late entry into the race. “They were angry then, and they’re angry now,” says University of Virginia political analyst Larry Sabato. “They’re puzzled and hurt, and they feel betrayed.” A former Virginia governor recently complained to Sabato about Perriello’s decision to run. “That was one of the most selfish things I’ve ever seen in politics,” the ex-governor groused, “and politics is a selfish profession!”

While both candidates have agreed to the standard pledge not to attack each other during the primary, it was clear at several town halls I attended that the Northam campaign has adopted a somewhat loose interpretation of the cease-fire. At the Mary Washington event in February, a young woman in the audience asks Perriello about his stance on abortion. As a congressman, Perriello had voted to block federal money from going to abortion providers—a position for which he has since apologized. “You used to say that you were not pro-choice,” the woman says, “and now you are pro-choice.” How could Perriello explain the flip-flop?

“I’ve always been pro-choice,” Perriello replies, practically sighing with exasperation. “I marched for Roe 25 years ago. I had a 100 percent NARAL rating my second year in Congress and supported funding for Planned Parenthood. After Congress, instead of taking a big lobbying job, I ran a progressive nonprofit organization”—the political action fund at the Center for American Progress—“that was central in fighting back against the war on women.”

I notice that the woman who asked the question is recording Perriello’s responses and carrying a spiral notebook. Assuming she’s a reporter, I approach her after the event and suggest that we compare notes. It turns out, in fact, that she’s an operative for the Northam campaign, dispatched to ask Perriello embarrassing questions about abortion. By early April, Northam had made the issue a centerpiece of his campaign, touting his endorsement by the pro-choice group NARAL and even holding rallies inside abortion clinics.

Gun control has also been a weak spot for Perriello. As a congressman, he opposed a federal ban on assault weapons and boasted about having an “A” rating from the National Rifle Association. In January, seeking to bolster his progressive bona fides, Perriello called the NRA a “nut-job extremist organization.” The Northam campaign has seized on the issue: At another town hall, I watch as a woman in the audience challenges Perriello about his views on guns. Afterwards, a veteran Democrat who is not affiliated with either campaign tells me that she recognizes the woman as another Northam operative.

Northam’s allies and supporters “have been raising unfair and inaccurate characterizations of Tom’s record for some time now,” says Perriello’s communications director, Ian Sams. “It’s unfortunate that the Northam campaign is allowing that to stand, and in some cases promoting it themselves. We would much prefer it be a positive campaign where both candidates lay out their positive visions for the state and let people decide based on that. But some of his allies and supporters have taken a different tack, and we certainly wish that the lieutenant governor would ask them to knock it off.” Asked about the town hall incidents, the Northam campaign declined to comment.

While such candidate-tracking is standard practice in political races, efforts by the Northam campaign to disrupt Perriello’s town hall meetings underscore the lengths to which the party establishment will go to tamp down enthusiasm for a grassroots candidate. And Northam’s focus on social issues comes straight out of Hillary Clinton’s playbook for taking on Bernie Sanders. In the final debate of the Democratic primary, Clinton attacked Sanders for supporting a bill that prevents victims of gun violence from suing gun manufacturers. “We hear a lot from Senator Sanders about the greed and recklessness of Wall Street, and I agree,” she said. “Well, what about the greed and recklessness of the gun manufacturers?”

The similarities between Perriello and Sanders are far from precise. In terms of style and temperament, Perriello is more jovial than Sanders, fond of corny jokes and the minutiae of policy. While he speaks passionately about corporations screwing middle- and working-class Americans, he lacks Bernie’s blunt outrage—he’s more Adlai Stevenson than William Jennings Bryan. And while his campaign manager, Julia Barnes, served as the national field director for Sanders, Ian Sams was a member of Clinton’s rapid response team. Perriello has also received endorsements from John Podesta and Neera Tanden—close allies of Hillary who worked with Perriello at the Center for American Progress—as well as Jennifer Palmieri, Teddy Goff, and other senior members of Clinton’s campaign staff. If the race between Perriello and Northam exposes the rift between the party’s establishment and its grassroots, it also suggests that the establishment can get behind an insurgent—provided the insurgent is affable rather than angry.

“I’m not sure that the gap between the wings of the party is actually as big as people think that it is,” Perriello says. He has taken to calling himself a “pragmatic populist”—someone who shares Bernie’s outrage over economic inequality, but who is intent on finding workable solutions. He has endeavored to pitch himself as a successor not so much to Sanders as to Obama: a young political outsider working to shake up the establishment, free of any personal or political baggage from the often acrimonious battle between Hillary and Bernie. Like Obama, he’s dynamic on the stump—though he lacks Obama’s trademark charm. At 42, Perriello is both single and single-minded, a man who gives the impression of being married to his job.

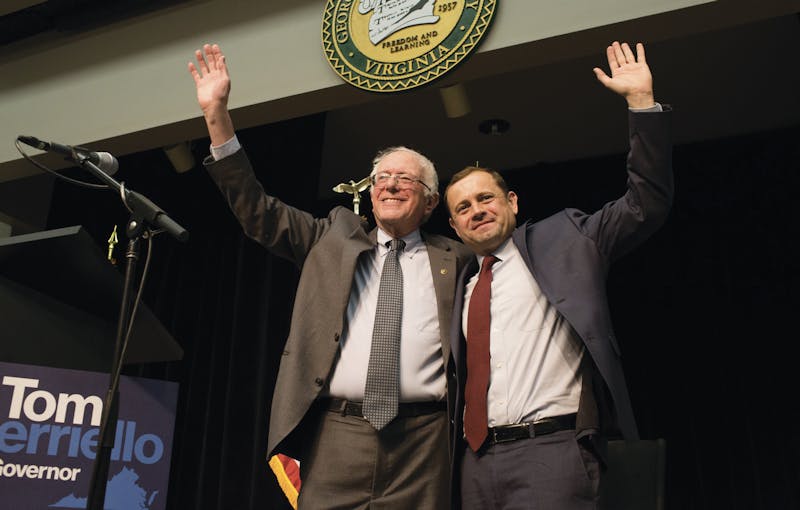

Still, despite resisting comparisons to Sanders, Perriello has enlisted Bernie’s digital outreach firm to shape his own fund-raising strategy. And in April he gladly accepted the support of Our Revolution, the nonprofit group that grew out of the Sanders campaign—as well as the endorsement of the senator himself. “We need to elect progressives at every level of government if we are going to beat back the dangerous agenda of the Trump administration and its Republican allies,” Sanders said. “Now more than ever we need people in elected office who will fight for middle-income and working families.”

Whatever happens in June, the outcome of the primary is likely to inform the party’s direction going forward. Virginia is shaping up to be the kind of state Ohio used to be: a microcosm of the nation itself, albeit one with a significantly higher number of people who work for the federal government. Virginia is a purple state that’s tracking blue—the only former Confederate state to throw its lot behind Clinton last year. “Virginia seceded from the South in 2016,” laughs Kidd, the Virginia pollster. Clinton won the state by five points, largely by running up the score in the wealthy, more liberal areas of suburban Washington.

But particularly in the aftermath of the 2016 debacle, a Democratic candidate for governor must perform well throughout the state—including in the coal-country counties of southwest Virginia that were dominated by Trump. Perriello’s campaign is an experiment: Can a left-wing candidate win back blue-collar and rural voters without sacrificing liberal votes? Is full-throated progressivism the best strategy for combating Trumpism? The idea that voters will rally behind a populist Democrat has yet to be tested, especially in a state like Virginia, and many veteran political observers are convinced that Northam’s down-home style will trump Perriello’s liberal substance. After all, much of Perriello’s fund-raising has come from outside Virginia, whereas 90 percent of Northam’s donations are from within the state. “Northam has a Virginia accent,” Sabato says. “He is rural by nature—grew up on the eastern shore. He went to the Virginia Military Institute. There’s no question in my mind that if anyone can draw in some conservatives, it’s Northam, not Perriello. They’re very suspicious of Yale-talking candidates.”

If Perriello loses, it will be seen as proof that the party establishment is right when it insists that left-wing policies don’t win elections. But if he wins, it will be yet another sign that the Sanders wing—and its more inclusive economic message—represents the party’s best hope for the future. In November, the winner of the primary will likely square off against Ed Gillespie, a former adviser to George W. Bush who served as chair of the Republican National Committee.

The high stakes aren’t lost on the people at the center of Perriello’s campaign. At his election headquarters, located in an office park in Alexandria, the walls smell of fresh paint, and the only decorations are a few haphazardly hung sheets of easel paper marked with illegible scribblings. Until recently, the campaign had been working out of Perriello’s Alexandria home. There’s no receptionist, so I just walk in and wander around until I find Julia Barnes and Ian Sams, the political odd couple who have helped engineer Perriello’s swift rise. After their stints with Bernie and Hillary, both contemplated getting out of politics. But inspired by what Perriello could mean for the party’s future, they signed up for one more round.

The campaign, Barnes says, will determine whether “the establishment in Virginia—and, by proxy, the establishment in the country—is going to be brave enough to set aside their fear and judgment.” The Democratic Party may be scared of change—of “being shaken to our core,” she says. “But we’ve got to shake a little to get there.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article stated that Leah Greenberg, one of Indivisible’s founders, serves as Tom Perriello’s policy director. In fact, since this story was reported, she left the Perriello campaign to serve full-time as Indivisible’s chief strategy officer.