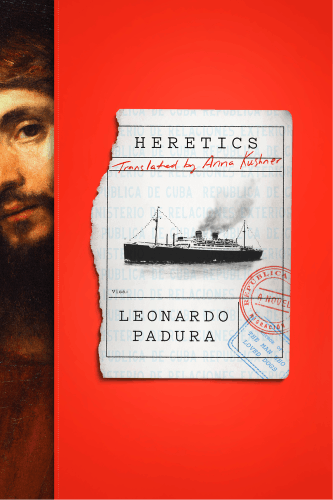

Leonardo Padura’s full name is Leonardo de la Caridad Padura Fuentes. Like his name, Padura’s new novel Heretics is long, elegant, a little religious in flavor, and invokes a great mononymous painter of the European past.

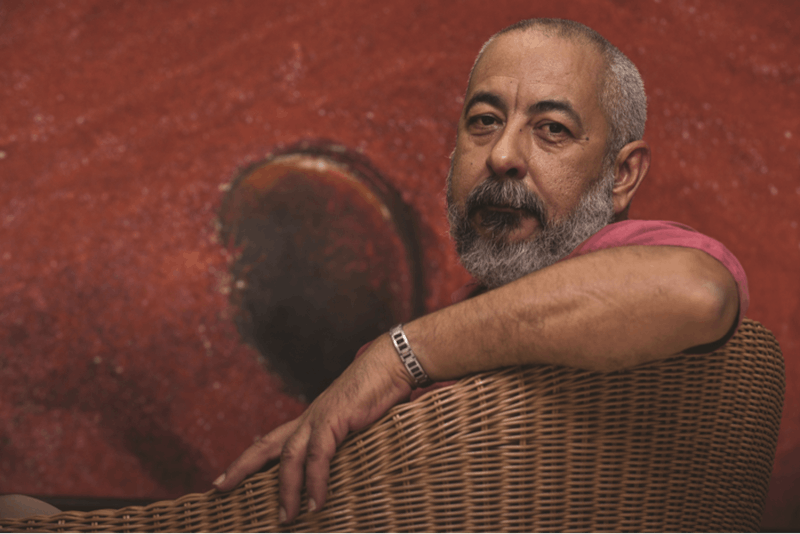

Padura is a Cuban writer who was mostly known as a writer of detective fiction until he published The Man Who Loved Dogs (2009), an experimental narrative telling the story of Trotsky’s assassination. (Padura first worked as an investigative journalist at a Cuban literary magazine called Caimán Barbudo, but little survives of that time except perhaps the inquisitive timbre of his fiction style.) In the New York Times, Alvaro Enrigue compared The Man Who Loved Dogs to Gabriel García Márquez’s Love in the Time of Cholera and Mario Vargas Llosa’s Conversation in the Cathedral, welcoming Padura into the Latin American Modernist canon.

That book, at nearly 600 pages, presented numerous difficulties for his translator Anna Kushner. In a 2014 interview with Guernica she described how the length of The Man Who Loved Dogs “wasn’t the biggest challenge. It was the fact that there were three distinct voices in the book.” In a style that shares qualities with crime writing in its thoroughness, almost its empiricism, Padura likes to approach the same event or enigma from several different angles. Heretics is a polyphonic narrative, with storytellers across continents and centuries unspooling a mystery through recollections, recollections of recollections once heard, letters, and more.

Mario Conde is a former cop enjoying his late-middle age in Havana. Conde was the protagonist of Padura’s old hardboiled works: Pasado perfecto (1991), Vientos de cuaresma (1994), Máscaras (1997), and Paisaje de otoño (1998). All those works were translated into English with the rather boring title formula of “Havana [Color]” (Havana Blue, Havana Red, and so on). But now Conde is older, and determined to stay out of the game until a young man named Elias asks for his help in tracking down a painting that was stolen from his family when they were fleeing the Holocaust. They were passengers on the St. Louis, the real Hamburg-to-Havana liner that President Federico Laredo Brú turned away from Cuba’s port in 1939. Of 937 on board only 28 passengers disembarked; the rest were sent back to their deaths. Elias’s father, Daniel Kaminsky, lost his family at the port. What happened to his inheritance, the Rembrandt portrait of a beautiful young Jewish man?

Each layer to this large and dense sponge-cake of a novel has a historicity that defines its voice, ethics, and subject matter. Conde in contemporary Havana speaks about rum and his girlfriend Tamara; Kaminsky the elder lives a Jewish Cuban life in the 1940s and 50s, losing his faith while becoming obsessed with baseball and his Russian neighbor’s pubic hair; Rembrandt and the Jewish subject of that long-lost painting mix pigments in seventeenth-century Amsterdam, surrounded by snow and tulip bulbs.

The title is not concerned with heresy in the Catholic sense, but the rabbinic institution of cherem: the total exclusion of a transgressor from the Jewish community (more comparable to vitandus excommunication). Since each generation of Jewish scholars must study, interpret, and re-rationalize the law for their own times, cherem is not a stable category. Padura uses Jewish scholarship as a medium for thinking about historical subjectivity.

Should one do what feels to be the right thing, and risk shunning by the community in which one happens to live? By asking this question of Jews in different times and places, Padura pulls a triptych of desire, convention, and choice out of history, a great complex lock to which cherem is the conceptual key.

Padura’s last novel was about Trotsky, who himself was the subject of a cherem in 1918, along with Grigory Zinoviev and others. The other book that Heretics recalls is Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch, which also uses a painting as its central organizing motif. Both Tartt and Padura employ the ekphrastic mode, using the paintings’ subjects—the delicate bird, the glowing Jewish young man—as stable weights at the heart of their stories. They are the central node in a constellation of ideas that are continually rearranging themselves.

When the young Daniel Kaminsky (Elias’s father) begins his life in Havana, he “quickly discovered that everything there began and ended with yelling, everything sputtered with rust and humidity.” Padura describes a tumult to Havana that ends up modeling how history operates in Heretics, a human and animal chaos that nonetheless hangs together into life itself:

…cars moved forward amid the wheezing and banging of engines or the long beeping of horns, dogs barked with and without reason and roosters even crowed at midnight, while each vendor made himself known with a toot, a bell, a trumpet, a whistle, a rattle, a flageolet, a melody in perfect pitch, or, simply, a shriek. He had run aground in a city in which, on top of it all, each night, at nine on the dot, cannon fire roared without any declaration of war or city gates to close, and where, in good times and bad, you always, always heard music, and not just that, singing.

We remember Rembrandt and his paintings, but most non-Jewish people have already forgotten the St. Louis. Padura’s novel does not just place dogma and religious law against human desire; he asks the reader to consider the relationship between the arts and discriminatory violence in our vision of the past. Heretics asks us what we remember, and why; do we know anything about our own grandparents’ traumas, and, if so, why is that generational memory easier to lose in time than a painting?

Law and art, art and the law: There is some kind of answer in that tension. History is a mess of dogs barking and shrieking and vendors’ bells, but human memory transforms that illicit noise into music, and not just that, singing.