Grace Paley may be the most underrated of New York twentieth-century writers. Born Grace Goodside in the Bronx, in 1922, she grew up in a Russian-Jewish family with strong socialist ideals. Paley studied poetry with W. H. Auden at the New School. Of Auden, she told the Paris Review that, “He seemed an immortal to me.” “I loved his poems so much,” Paley said, “that I was using this British language all the time—I was saying trousers and subaltern and things like that.” They once arranged to meet up in a café, which she didn’t realize had two branches. She thought Auden had stood her up.

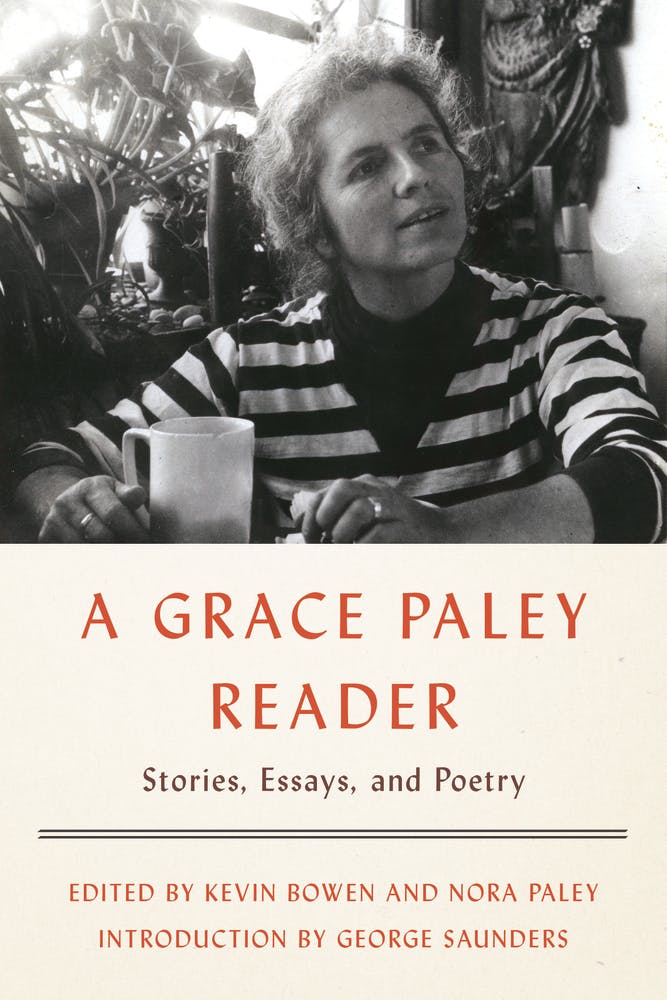

From this wobbly and imitative origin Paley’s voice grew distinct—and multitudinous. In his introduction to A Grace Paley Reader (edited by Kevin Bowen and Nora Paley), George Saunders resorts to exclamations: “All these agitated manic New York voices explaining themselves!” Saunders’s reactions are exclamatory because they are intense: Everybody who knows Paley’s writing adores her. But Saunders also finds a revelatory force in Paley’s observations of everyday life that is something like love, and it’s hard to do anything but exclaim about that.

The anthology selects Paley’s stories, essays, and poetry. Like Saunders, I care most about her fiction, because it is the most unusual part of the Paley oeuvre. The essays about her time in women’s collectives and protesting the American government’s warmongering are important artifacts and teach us much about a movement whose ideas and activism are resurging among young people now. The poems are nice but a bit sentimental. The stories are just themselves, which is a hard thing to describe.

Paley’s fiction is almost exclusively about unmoneyed motherhood in New York City. The character of Faith is Paley’s own avatar, a woman whose small children are totally imbricated into her inner monologue. The story “Faith in a Tree,” from her second short fiction collection Enormous Changes at the Last Minute, is about taking the kids to the park. Of her eldest, Ricardo, Faith muses: “See how beautiful the ice is on the river, see the stony palisades, I said, I hugged him, my pussycat, I said, see the interesting world.” Beholding the world’s details and making them a part of the child’s experience, who is himself a part of the mother’s sensory world: that is Faith’s mode.

Saunders calls this love, this feeling for the glory and pain of the everyday. In “Faith in a Tree,” we drift in and out of conversations, memories, observations. Faith’s “up-the-block neighbor” is Mrs. Junius Finn, “a broad barge, like a lady, moving slow—a couple of redheaded cabooses dragged by clothesline at her stern.” The women call to one another, voices bouncing from tree to path to earth while the children toddle about. “Mrs. Finn goes puff puffing toward the opinionated playground, that sandy harbor.”

In that Paris Review interview, Paley explains that at the time she began writing stories she “was hanging out a lot.” She describes herself as “kind of lazy,” but adds, “Thank God I was lazy enough to spend all that time in Washington Square Park.” That was when Paley “began to know women very well—as co-workers, really,” and she found her subject.

Paley became a knower of women, a conscious feminist, and a writer all at once. In the essay “Of Poetry and Women and the World,” she expands on this time and the link between women and fiction in her life. “When I came to think as a writer, it was because I had begun to live among women,” she writes. But this did not mean that she understood them. No, “the great thing is that I didn’t know them, I didn’t know who they were.” Instead, it was Paley’s lack of understanding of the domestic lives of women that provoked her writerly fascination. That ignorance “is really where lots of literature comes from,” she writes. “It really comes, not from knowing so much, but from not knowing. It comes from what you’re curious about. It comes from what obsesses you.”

Although that obsession could feel limiting, it gave her constraints from within which to dig deeper. “I was writing stuff that was trivial, stupid, boring, domestic, and not interesting,” she continues in the same essay. “However, it began to appear that that was all I could do, and I said, ‘Okay, this is my limitation, this is my profound interest, this life of women, and this is what I really have to do.’” Limitation, for Gracey Paley, became the same phenomenon as inspiration.

In his introduction, Saunders makes a strange comparison. He draws a parallel between Paley and David Foster Wallace, although the latter wrote about the world outside of himself with a plunging-in attitude that does not resemble Paley’s at all. But “Paley and Wallace were both very special human beings,” Saunders writes. Each were “composed of mostly primary qualities, with very little of what we might call banal/normalized pollution.”

I think what Saunders means is that both Paley and Wallace engaged in a kind of ecstatic direct experience and tried to render that direct ecstasy into words. There are many fictions of motherhood, and many leftist essays about socialism and the need to end war. There are also many women who deserve to be reclaimed from the obscurity in which so many great American post-war writers languish. There are many generous writers, and many who cared more for living and writing and their families than they cared for fame. But of all these Grace Paley is one of the very best, which A Grace Paley Reader knows.