America drove the Bahar family from their country. Then it gave them a new one.

The Bahars fled Iraq in 2006, at the height of the U.S. invasion. They left because of the things their eldest son saw—the bombings and shoot-outs, the kidnappings, the everyday horrors of life in a war zone—and because of the things he could not see. Karar was born in 2002 with an eye condition that caused his retinas to develop too slowly. But with hospitals in Baghdad overrun with wartime casualties, doctors had no time for a tottering little boy who could barely make out cartoons on television.

The family moved to Cairo, but specialists there were unable to help. So the Bahars decided to apply for asylum in the United States. After a year of interviews, background checks, and reams of paperwork, the family landed in Ohio on December 10, 2009. They caught their first glimpse of snow dusting the wings of airplanes grounded on the runway, and waded into the Midwestern frost wearing all the layers they had. A local charity set them up with an apartment, but it came sparsely furnished, so they had their first American dinner of spaghetti and chicken fingers sitting on the floor.

“I didn’t know anything about America,” recalls Haider, Karar’s father. “I didn’t speak English, I didn’t know where I was going, I didn’t know if I’d find a job or not.”

With the help of his landlord, Haider got a job in the meat department at a Kroger supermarket in Columbus. His colleagues were kind and corrected his English; the local mosque was next to a church, and Haider didn’t meet anyone who had a problem with the family’s Muslim faith. His wife, Shaimaa, learned to navigate the school system and get medical help for Karar, now a typical American teenager who loves the Ohio State Buckeyes and fried chicken and hanging out with his friends.

Photographer Holly Pickett has spent nine years following the Bahars from Cairo to Columbus. In 2015, they became U.S. citizens. “When I got citizenship, I felt different,” Haider recalls. “I finally saw a future, and felt sure that my kids would have a good life.” Last year, he and Shaimaa voted in their first American election. She backed Hillary Clinton, because of her support for women, Medicaid, and refugees. Haider picked Donald Trump, because of his promises to bring back jobs to the area.

If Trump had been president when the Bahars sought asylum, they might never have become U.S. citizens. And if Trump succeeds at imposing his travel ban on Iraq, they could be permanently separated from their family in Baghdad. Haider’s father still hasn’t met his youngest grandchildren—Renad, five, and Mustafa, six months.

Haider, now a patriotic American, admits he is worried. But he’s willing to give the new president a chance. “I wish my family could come here,” he says. “But it’s only for three months. Donald Trump knows what’s going on.”

In Cairo, doctors were unable to treat Karar’s eyesight, and the family sank into debt. One day, while the children were napping, Shaimaa broke down in tears. “She was tired, tired,” recalls her husband, Haider. “The money was gone, and we didn’t have insurance.” Worse, the Bahars didn’t know where they’d be in a week, a month, a year.

The Bahars depart Cairo International Airport with all their belongings on December 9, 2009, bound for Ohio. That year nearly 50,000 Iraqis were referred to the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program. With the help of a legal aid group in Cairo, the Bahars were among the 25,238 granted approval to start a new life in America.

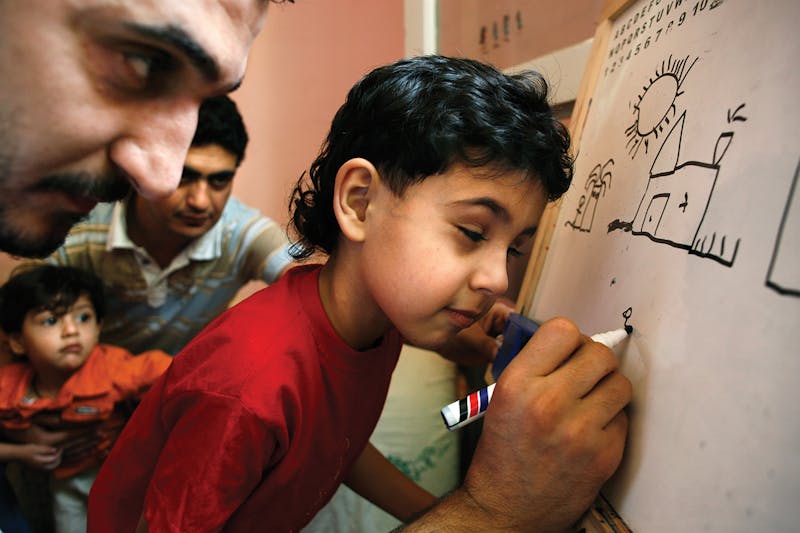

Karar, with a new pair of glasses, sits close to the teacher in his second-grade class in Ohio. “I was lost,” he recalls. “I came in barely knowing numbers. But people weren’t rude—they were helpful.”

Thanks to a tip from his landlord, Haider soon found work in the meat department at a Kroger supermarket. He now delivers medicines to local pharmacies, earning $6 a stop. Money is tight, but little by little, the family has managed to buy used furniture and even take vacations.

Shaimaa and Haider crammed for the U.S. citizenship exam together. Shaimaa took the oath on January 14, 2015, and Haider followed three months later. “I finally saw a future,” he says. During the ceremony, the judge let Karar sit in one of the jury seats. “That made me feel wonderful,” he recalls.

The Bahars have made an annual tradition of celebrating their arrival in America. “We all remember,” Haider says. “It’s like a birthday.” For their fifth anniversary, they went to a fried-chicken restaurant in Columbus. “The best thing is the sauce,” says Karar. “It’s not spicy, but it has a punch.”

Shaimaa braids Renad’s hair at the family’s home earlier this year. The five-year-old loves to dress up as Minnie Mouse and to wear a blue toy crown.

The family uses Viber to stay in touch with their relatives in Iraq. Every week, Haider calls his brother and elderly father, neither of whom have met the family’s newest addition, six-month-old Mustafa. The Bahars do not know when—or if—their relatives will ever be allowed to visit them in Ohio: Since his first week in office, Trump has been trying to ban all travel from Iraq.

Karar, now 15, attends middle school in Dublin, Ohio. “Last semester I got out with 4.0, honor roll, all the good stuff,” he says. He still struggles with his eyesight—“I’m basically blind,” he jokes—but he dreams of playing basketball and attending college. He has no desire to return to Iraq. “When you see something scarring,” he says, “it’ll last for a whole lifetime.”

Haider, who voted for Trump, watches the president defend his ban on immigration, while Mustafa sleeps. “I feel bad for guys like me,” Haider says. “I feel what these guys who want to come here are feeling.” He and Shaimaa didn’t argue over her support for Clinton. “I can’t tell her who to vote for,” he says. “That’s American freedom.”