You can learn a lot about a culture from its drug use. Robert McAlmon, an American author living in Berlin during the tumultuous Weimar years, marveled that “dope, mostly cocaine, was to be had in profusion” at “dreary night clubs” where “poverty-stricken boys and girls of good German families sold it, and took it.” Cocaine was banned in 1924, though few people noticed—use peaked three years later. For those who preferred downers, morphine was just as easily accessible. Pharmacists legally prescribed the opioid for non-serious ailments, and morphine addiction was common among World War One veterans. The market was bolstered by low prices—for Americans, McAlmon noted that enough cocaine for “quite too much excitement” cost about ten cents—and by the fact that production was more or less local. In the 1920s, German companies generated 40 percent of the world’s morphine, and controlled 80 percent of the global cocaine market.

When the Nazis rose to power, illegal drug consumption fell. Suddenly, drugs were regarded as “toxic” to the German body, and folded into the escalating discourse of anti-Semitism. Users were penalized with prison sentences, and addicts were classed—along with Jews, gypsies and homosexuals—as undesirable social elements. By the end of the 1930s, pharmaceutical production had pivoted away from opioids and cocaine and towards synthetic stimulants that could be produced entirely within Germany, per Nazi directive. The transition from cabaret cocaine to over-the-counter meth helped fuel what German journalist Norman Ohler in his new book Blitzed: Drugs in the Third Reich calls the “developing performance society” of the early Nazi era, and primed Germany for the war to come.

The breakthrough moment came in 1937, when the Temmler-Werke company introduced Pervitin, a methamphetamine-based stimulant. (The doctor who developed it, Fritz Hauschild, would go on to pioneer East Germany’s sports doping program.) Within months, this variant of crystal meth was available without a prescription—even sold in boxed chocolates—and was widely adopted by all sectors of society to elevate mood, control weight gain, and increase productivity. It’s impossible to untangle Pervitin’s success from Germany’s rapidly changing economic fortunes under the Third Reich. As the country rebounded from economic depression to nearly full employment, marketing for Pervitin claimed it would help “integrate shirkers, malingerers, defeatists and whiners” into the rapidly expanding workforce. Students took it to cram for exams; housewives took it to stave off depression. Pervitin use was so common as to be unremarkable, a feature of life in the early Third Reich.

Meanwhile, in the military, Pervitin was enthusiastically embraced as the vanguard of the so-called “war on exhaustion.” As Hitler’s troops began annexing territory in the spring of 1939, Wehrmacht soldiers started relying on “tank chocolate” to keep them alert for days on end. Though Nazi medical officials were increasingly aware of Pervitin’s risks—tests found that soldiers’ critical thinking skills declined the longer they stayed awake—the short-term gains were appealing enough. Even after drug sales to the general public were restricted in April 1940, the German Army High Command issued the so-called “stimulant decree,” ordering Temmler to produce 35 million tablets for military use.

With the war ramping up, the reason behind this decree would soon become clear. A month later, on the night of May 10, 1940, more than 40,000 army vehicles amassed near the German border with Luxembourg for a daring advance that would take them through the Ardennes forest and across the French border in a single push. In preparation, thousands of soldiers were given Pervitin:

Twenty minutes later, the nerve cells in their brains started releasing the neurotransmitters. All of a sudden, dopamine and noradrenalin intensified perception and put the soldiers in a state of absolute alertness. The night brightened: no one would sleep, lights were turned on, and the ‘Lindworm’ of the Wehrmacht started eating its way tirelessly towards Belgium…

Three sleepless days later, the Nazis were in France. The stunned Allies were closer to defeat than they would be at any other point during the war. As Ohler writes in Blitzed, the Germans had claimed more land in less than a hundred hours than they had over the entire course of World War One.

Blitzed, which was a bestseller in Germany, is comprised of two main parts: A look at the effects of drugs on the German military, and on the Führer himself. While Hitler’s medical records have been scrutinized for decades—first by wartime American intelligence agencies, and more recently, by scholars Hans-Joachim Neumann and Henrik Eberle in Was Hitler Ill?—Ohler spent five years in international archives mounting a case that the dictator was not merely suffering from stress or madness, but drug-induced psychosis, which fueled his lethal tendencies.

This is Ohler’s

first nonfiction book (he’s written three novels) and the first popular book of

its kind, filling a gap between specialist academic literature and

sensationalist TV documentaries. There’s a contemporary Berlin sensibility to Blitzed: Ohler came upon the idea after

a local DJ told him that the Nazis “took loads of drugs,” and his archival

research is interspersed with accounts of urban exploring at the former Temmler

factory. The hipster-as-historian persona occasionally feels forced—Ohler characterizes

Hitler as a junkie and his doctors as dealers a few too many times—but the book

is an impressive work of scholarship, with more than two dozen pages of

footnotes and the blessing of esteemed World War Two historians. From Hitler’s irregular

hours and unusual dietary preferences—his staff would leave out apple raisin

cakes for him to eat in the middle of the night—to his increasingly monomaniacal

demands, Ohler offers a compelling explanation for Hitler’s erratic behavior in

the final years of the war, and how the

biomedical landscape of the time affected the way history unfolded.

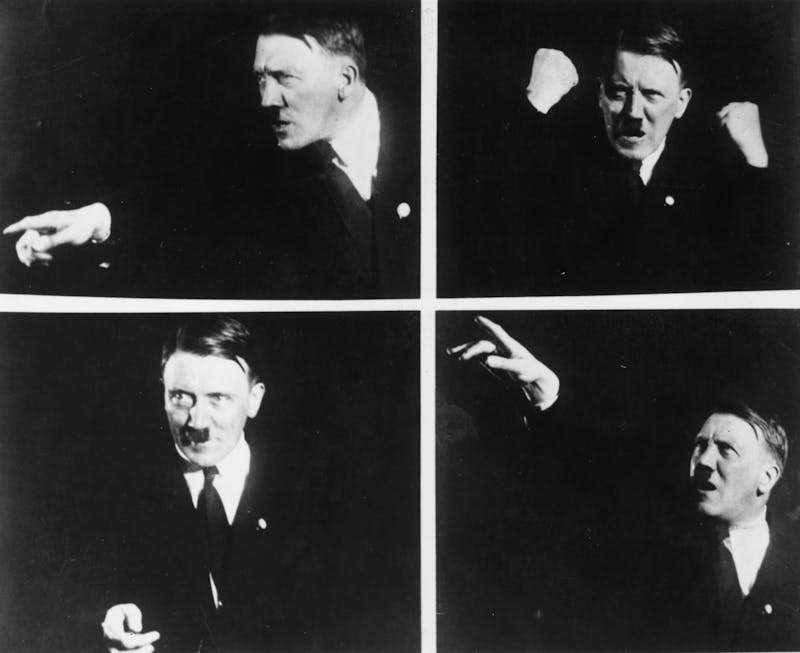

Over the past half-century, discussions about Hitler’s health have touched lightly on Dr. Theodor Morell, a private practitioner who specialized in dermatology and venereal diseases before becoming the Führer’s personal physician in 1936. According to Ohler, Morell’s role was far greater than previously acknowledged. Despite being widely regarded as a fraud, Morell was granted more access to Hitler than anybody other than Eva Braun. During the nine years the doctor treated Hitler, he is believed to have given the Führer between 28 and 90 different drugs, including Pervitin, laxatives, anti-gas pills with strychnine in them, morphine derivatives, seminal extract from bulls, body-building supplements, digestives, sedatives, hormones, and many vitamins of mysterious provenance, mostly administered via injection. This all happened quietly, as the myth of Hitler-as-teetotaler was central to Nazi ideology: “Hitler allegedly didn’t even allow himself coffee and legend had it that after the First World War he threw his last pack of cigarettes into the Danube,” Ohler writes. Luckily, Morell left detailed accounts of Hitler’s medical records, likely believing that if anything happened to “Patient A,” he would be held responsible.

Hitler did not have any serious medical conditions at the start of the war—he suffered from painful gas, believed to be the result of his vegetarianism—but over the years, he came to rely more and more on Morell’s injections. After the fall of 1941, when the war began to turn in the Allies’ favor—and, Ohler observes, the “dip in Hitler’s performance became obvious”—they took on greater potency. One night in the summer of 1943, Hitler awoke with violent stomach cramps. Knowing he was scheduled to meet Mussolini the next day, Morell gave the Führer his first dose of Eukadol, an Oxycodone-based drug that was twice as strong as morphine. It had the desired effect: Hitler ranted through the meeting, preventing Mussolini from pulling Italy out of the war. The Führer was delighted; Morell remained firmly in Hitler’s good graces.

Records show that Eukodol was administered only 24 more times between that night and the end of 1944, but Ohler suspects that the coded reports disguise a much higher number. “This approach to the dictator’s health,” he writes of the injections, “could be compared to using a sledgehammer to crack a walnut.”

Aside from power and prestige, there were lucrative reasons for men unconcerned with morality to work for the Third Reich. Before becoming Hitler’s physician, Morell made a name for himself in the emerging field of vitamins, becoming one of the first doctors in Germany to promote them as medicinal. Following his appointment, Morell used his role to develop his vanity vitamin business, enlisting Hitler as his “gold standard” patient.

To this end, Morell developed a preparation called Vitamultin that he marketed across Europe, with special packaging for Hitler’s personal vitamins, and another for those of high-ranking Nazi officials. Though they mostly consisted of dried lemon, milk and sugar, the SS ordered hundreds of millions of tablets; the Nazi trade unions requested nearly a billion. Pleased with his returns, Morell went on to take over an “Aryanized” cooking-oil company in Czechoslovakia, which he converted into a factory for vitamin production. Soon after, he advanced plans to construct an “organotherapeutic factory” which would manufacture hormones preparations from slaughterhouse leftovers.

By 1943, Morell was a one-man empire, and not even a ban on introducing new medication to the German market could stop him. “The Führer has authorized me to do the following,” he wrote in a letter to the Reich Health Office. “If I bring out and test a remedy and then apply it in the Führer’s headquarters, and apply it successfully, then it can be applied elsewhere in Germany and no longer needs authorization.”

A number of books have covered the same material as Ohler, but none have focused as strongly on how pharmaceuticals ran in the blood of the Third Reich. Pervitin, Eukodal, and other “wonder drugs” of the time were seen as the magic bullets that would allow German productivity to reach new heights, German soldiers to march farther, stay awake longer, and, ironically, cleanse the country of its toxic elements. It was only later, Ohler notes, that the effects would become clear:

Studies show that two thirds of those who take crystal meth excessively suffer from psychosis after three years. Since Pervitin and crystal meth have the same active ingredient, and countless soldiers had been taking it more or less regularly since the invasion of Poland, the Blitzkrieg on France, or the attack on the Soviet Union, we must assume psychotic side-effects, as well as the need to keep increasing the dosage to achieve a noticeable effect.

As it became

obvious the Nazis were going to lose, military efforts became increasingly

desperate, and life was cheaply traded for grasping attempts at victory.

Teenage recruits were dosed with amphetamines and shipped to the front; Navy

pharmacologists tested dangerous mixes of high-grade pharmaceuticals on pilots.

At a wine bar in Munich, Ohler meets with a Navy official who tells him how in

the final months of the war, members of the Hitler Youth were loaded into

mini-submarines and sent to sea with not much more than packets of cocaine

chewing gum.

The last days of the Third Reich were marked by a combination of delirium and exhaustion. In January 1945, with the Russians and Allies closing in, Hitler was transferred to an underground bunker beneath the Reich Chancellery. By that point, his addiction and physical deterioration were apparent: He was barely able to sleep or focus, and was regularly receiving Eukodol injections for painful constipation and seizures. Or, at least he had been—in the weeks leading up to the new year, the British bombed the pharmaceutical companies that manufactured Eukadol and cocaine, threatening Hitler’s supply. In the months that followed, his reserve of drugs drawing down, he likely went through a brutal withdrawal. He sacked Morell on April 17, and two weeks later, shot himself.

Ohler’s book makes a powerful case for the centrality of drugs to the Nazi war effort, and had he wanted to, he could have easily made it two or three times as long. He only briefly touches on drug experimentation in concentration camps, and doesn’t explore the structural ties that existed between the Third Reich and German pharmaceutical companies, which would come to light during the Nuremberg Trials. Without these relationships, it’s unlikely the German war machine would have run for as long as it did. After supporting the Nazis’ rise to power, pharmaceutical conglomerate I.G. Farben developed the nerve gas used in the camps, and produced oil and synthetic rubber for war efforts. In 1942, Farben set up Auschwitz-Monowitz, a smaller concentration camp within Auschwitz, to provide slave labor for the company’s nearby industrial complex. Tens of thousands of inmates died as a result of experimentation and forced labor, and the development of thalidomide, notorious for causing deformities in fetuses, has been linked to Monowitz.

Ohler also doesn’t mention that the amphetamine craze didn’t only happen in Germany. While Germans were dosing with Pervitin, British and American troops were doing the same with Benzedrine, an amphetamine developed in the ‘30s as the first prescription anti-depressant. (Benzedrine was the ancestor of medications now prescribed for attention-deficient disorder.) The Germans eventually decided to drop Pervitin as the war dragged on, but the American military stuck with “bennies,” and by the end of 1945, production was up to a million tablets a day.

The notion that substances play an outsized role in shaping society—and especially during wartime—does not just belong to history. Amphetamines still factor heavily in conflicts in Syria (Captagon), Afghanistan (Dexedrine), and West Africa (cocaine mixed with gunpowder). Thanks to pharmacological advances, we’re now more able than ever to grasp how drugs may have altered behaviors and influenced certain moments. Knowing that Eukadol and Pervitin contributed to the grotesqueries of Nazi military strategy, for instance, places a new lens on a disturbing chapter of history.