In 1948, James Baldwin left Harlem for Paris to save himself. After his friend Eugene Worth jumped off the George Washington Bridge to his death, Baldwin was afraid that he would suffer a similar fate. In a 1984 interview with The Paris Review, he said: “My luck was running out. I was going to go to jail, I was going to kill somebody or be killed.” It was because of this desire to escape the dire situation of being a black male in America that Baldwin found himself alone in France with only $40 in his pockets. Years later, Baldwin would write a series of essays reflecting on his Paris years. It was in Paris that he found his voice and also came to understand the complexity of his American identity. “The very word ‘America,’” Baldwin wrote in his 1959 essay “The Discovery of What It Means to be An American,” “remains a new, almost completely undefined and extremely controversial proper noun. No one in the world seems to know exactly what it describes, not even we motley millions who call ourselves Americans.”

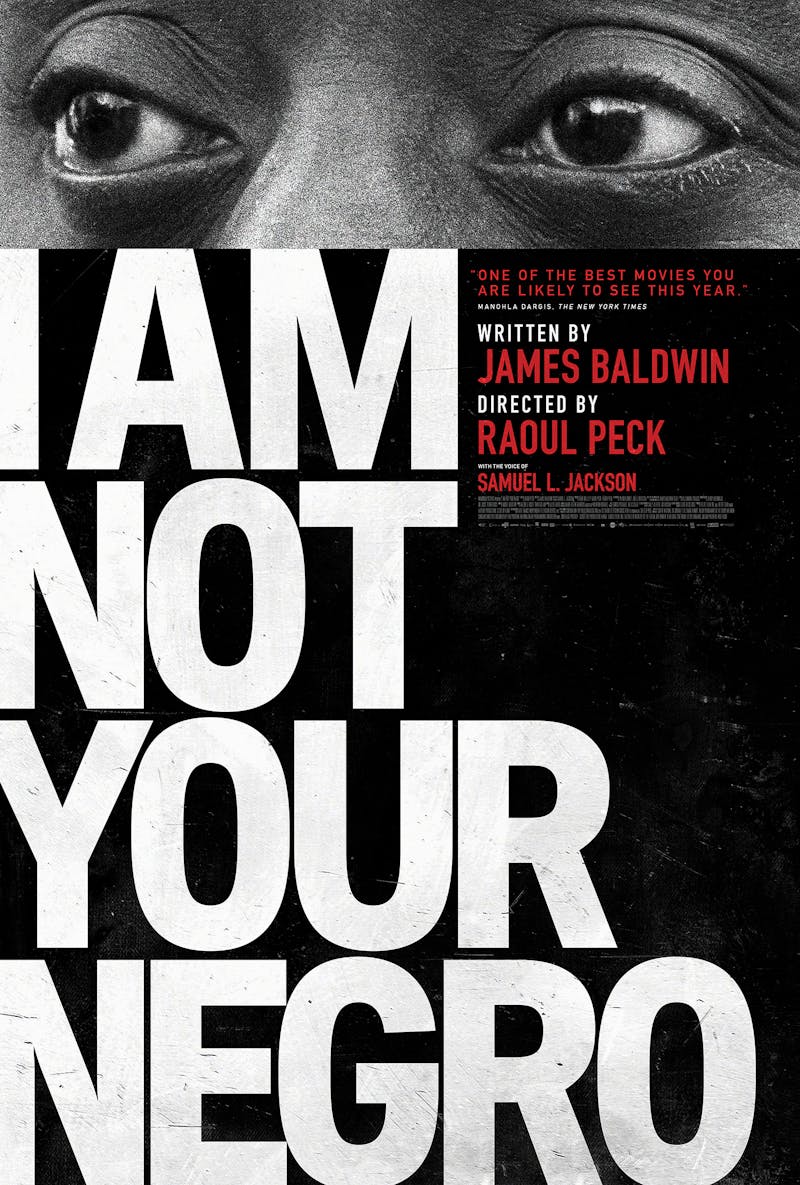

Raoul Peck’s I Am Not Your Negro, which opens on Friday in select theaters around the country, revisits Baldwin’s interrogation of what it means to be American. The film is not just a factual report about a particular event or person. Like the famed works that are its inspiration, it is an essay. And like any good essay, it begins with one question, and, over the course of its 90 minutes, asks a set of new ones. Similar to its literary counterpart, the essay-film escapes clear definition. It is the problematic stepchild in a world insistent on categorization. But the film’s troublesome, inquisitive nature is in keeping with what Montaigne, the inventor of the essay, meant his “Essais” to be—attempts, trials, experiments.

Our experiment begins with a note Baldwin wrote to his literary agent Jay Acton in 1979. It is read by Samuel L. Jackson, whose voiceover proves oddly comforting over the course of the film (Baldwin is credited as the movie’s only writer). In the letter, Baldwin proposes a new project about the Civil Rights Movement driven by the narratives of three of its famous leaders—Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and Medgar Evers. It would require him to travel to the homes of these murdered men and speak with their families—to be a witness to the lives they lived. But Baldwin’s own death in 1987 from cancer left the project unfinished. Its 30 pages of notes—provisionally titled, Remember This House—are the basis for Peck’s film.

He has filled in this skeletal framework with excerpts from Baldwin’s other essays, clips of his spirited debates and roundtable appearances, and archival footage from Baldwin’s time. Peck is not concerned with presenting the biographical details of Baldwin’s life. What follows, instead, is Baldwin’s strong, personal point of view on the question at hand, told in a voice that now seems prophetic. The film is loosely organized into thematic chapters: Paying My Dues, Heroes, Witness, Purity, Selling the Negro, and I Am Not a Nigger.

In Witness, Baldwin’s beautiful prose paints an intimate portrait of the larger-than-life figures who are his subjects. “Malcolm was sitting in the first row of the hall, bending forward at such an angle that his long arms nearly caressed the ankles of his long legs, staring up at me,” he writes of the first time he met Malcolm X. The gentleness in that “caress” gestures at an interiority often missing from depictions of heroes of the 1960s, particularly a firebrand like Malcolm X. This section also provides a clear example of the self-interrogation the Montaignian essay aspires to. When describing a trip he took with Medgar Evers, Baldwin writes that he “was to discover that the line which separates a witness from an actor is a very thin line indeed.” Baldwin says he was troubled by the passivity required of witnesses. The former expatriate describes how he was not a member of black civil rights groups like the Black Panther Party, the NAACP, or the church. He admits that he did not help with voter registration or strategize a way to political victory, and though this was “hard on [his] morale,” he accepted that his role as a writer required distance.

Baldwin, of course, is also famous for his interrogation of white Americans and their own self-delusions. In Heroes, Baldwin tells the story of a white female teacher in his grade school who took an interest in him. Peck chooses to use footage from the 1933 movie King Kong as a backdrop, with its famous scene of the giant gorilla holding a frail white woman in his simian grip. Together they constitute a commentary on the way perceived notions about white femininity have curtailed black liberation efforts. In Purity, Peck plays a clip from 1950’s No Way Out, starring Sidney Poitier, a reoccurring figure in the film who represents a white ideal of black assimilation. “They said it wasn’t nice to say nigger. Nigger! Nigger! Nigger! Poor little nigger kids, love the little nigger kids. Who loved me? Who loved me?” says Richard Widmark’s character Ray, a white bigoted criminal who comes under the care of Poitier, a doctor in a hospital prison ward. Ray’s words feel less angry and more anxious against Baldwin’s analysis of how racial constructs poison the minds of all who are trapped in them. “The problem, which they invented,” Jackson reads, “has made of them criminals and monsters, and it is destroying them.”

In moments like these, Peck effectively channels Baldwin’s essayistic style. But at times, Peck struggles to maintain the balance between words and images. For example, a video of Mars’s surface as Baldwin’s words echo in the background (“White people are endlessly demanding to be reassured that Birmingham is really on Mars”) speaks too literally to the text.

Like everything else these days, I Am Not Your Negro cannot be viewed outside our current political context. We are living in a time in which white anxiety about change has catapulted a bigot into the Oval Office. This attaches new urgency to Baldwin’s words, particularly the criticism he inflicts on himself for being a mere witness. But to distance does not mean to disengage. To witness is to be present; to testify, hopefully, to a truth. It takes courage to be a witness just as it takes courage to be an actor.

Americans like to believe themselves witnesses. Undergirding our understanding of history is a belief that if we had been present, we would have done things differently—been more outspoken, braver, than our forebears. But this is much easier said than done, and our present moment attests to that. Most of us are observers, not actors; most of us are spectators, not witnesses. The last half of I Am Not Your Negro moves out of the lives of Malcolm, Martin, and Medgar and takes a broader look at American culture. Over clips of daytime dramas like The Steve Wilkos Show and The Jerry Springer Show, Jackson reads Baldwin’s prescient commentary:

“To watch the TV screen for any length of time is to learn some really frightening things about the American sense of reality. We are cruelly trapped between what we would like to be and what we actually are. And we cannot possibly become what we would like to be until we are willing to ask ourselves just why the lives we lead on this continent are mainly so empty, so tame, and so ugly. These images are designed not to trouble, but to reassure. They also weaken our ability to deal with the world as it is, ourselves as we are.”

Americans in the age of Trump are undergoing a painful period of self-reflection. The election of a reality television star to the highest office in the land would be disconcerting on its own. But the fact that this same star proved time and again that he has no respect for women, minorities, and the disabled makes his election that much harder to understand. In his first two weeks as president, Trump has delivered on many of his bigoted campaign commitments, including initiating plans for a wall on the Mexico-U.S. border and barring immigration from seven predominantly Muslim nations. Every hour of every day seemingly brings a new horror, things that were once thought unimaginable. The result has been overwhelming action on the part of citizens. People have taken to the streets and called their senators.

But to transition from spectator to witness is a long and difficult process. It requires a return to the past, an understanding of this country in its totality. There must be an acknowledgement that the groundwork for this moment began not in 2008, with the election of this country’s first black president, but in 1776, with the founding of this republic. There must be a widespread awareness that we are all implicated in the crimes of the past. I Am Not Your Negro is not a film that actually says anything new about the America that we live in. Its thesis is tired and worn. But this is not the fault of the film, just of a country that refuses to truly bear witness.