There is nothing I’m more curious about than money. Whenever I visit a friend’s apartment, I wonder how much they pay in rent. Whenever I’m at a museum, I wish the title placards included a price. I hate being kept from any type of information, but financial withholding is especially intolerable. “How much did you pay for that?” would be the question I most frequently wish I could ask if it weren’t edged out by the even more compelling, “how much did you get paid for that?”

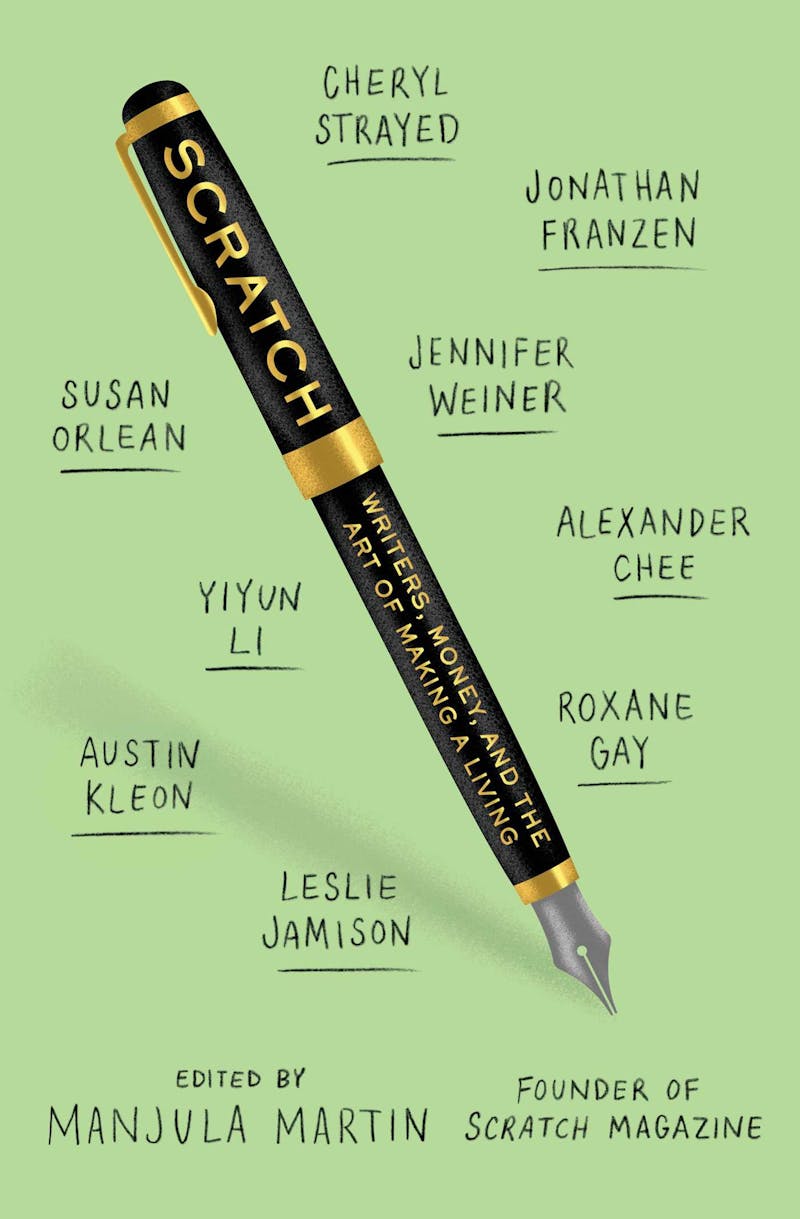

By dint of its focus, then, Scratch: Writers, Money, and The Art of Making a Living, was guaranteed to excite me, and its execution didn’t disappoint. In this impressive anthology, thirty-three widely published writers consider the exhaustion that accompanies freelance hustling, the scattershot nature of success, and the impossibility of a steady paycheck. In the best parts, they also share exactly how much they got paid—on the occasions they got paid at all. Authors like Roxanne Gay and Cheryl Strayed offer up figures with no hedging or obfuscation (“Last year, I probably made about $150,000”; “I had accrued $50,000 in credit card debt to write that book.”) and it is exhilarating.

The promise of Scratch isn’t that the featured writers will divulge every work-related figure of their careers. (Though that would be sublime.) Essays like Rachel Maddux’s “On Staying Hungry,” about an “ambition fast” designed to remind her what she was “writing toward,” and Leslie Jamison’s “Against ‘Vs.’,” on “our abiding discomfort with the idea of art produced by context,” are valuable in spite of being integer-free. But even the loveliest selection about staying true to a financially ruinous inner compass (Sarah Smarsh’s “The Jump”) fades against pieces that bolt practical information to the specificities of circumstance. Sari Botton’s “Ghost Stories,” about her experience in ghost-writing, is exemplary in this regard, linking every number with a details of the exact job: How it was sold to her, what it truly involved, how it ended. She’s told one eventual bestseller won’t be big and so it’s ok to consent to no royalties. She makes the most she’s ever made on a book from which she’s eventually fired.

Not that every contributor is so forthcoming. When Susan Orlean sidesteps numbers with “it’s a very personal thing,” and Austin Kleon demurs, “I can’t think of any way that my family or I would benefit from letting other people know the exact amount of money I make,” I almost booed out loud. The performance of work for wage is a principal aspect of social life and so cannot be convincingly treated as something deeply private. It’s not mere prurience that inspires lists of the world’s richest people, or of the best-paying professions—or of the worst-paying ones. It’s an interest in understanding how capital moves within and structures our world. Money matters.

“No one knows what anything is or should be worth,” Susie Cagle writes in “Economies 101,” identifying the confusion that characterizes late capitalism, but also speaking to the plight of many writers who struggle for years, even after being regularly published: How much should my writing—my expertise, my time, my talent, my experience—earn me? To live in this numerical void is to live in a state of vulnerability.

Cagle’s observation is even more poignant because it comes after one of the saddest passages in the entire book (also hers):

I began reaching out to friends and colleagues also working piecemeal. They were supportive but territorial. They were slipping, too. We all put on a strange public face—at once successful and satisfied with our work, but also ever hungry for more, for better. We hid from each other, too. We still do.

If you’re a writer who’s already established yourself as a profitable commodity, Kleon’s words are true; you probably aren’t going to benefit much from greater circulation of income-related information, at least not when it comes to you making more money. But that’s not why you’d offer such information up. You’d do it in the interest of creating a more hospitable space for other writers. You do it because you don’t only love writing, you love reading. You’d do it for those who aren’t as lucky as you, because you are in a position of privilege and it’s a gesture that costs you nothing beyond a moment of self-conscious discomfort. (One ugly reality Scratch never denies is that luck, and racism, have a tremendous amount to do with the trajectory of a writer’s career.)

One might attribute such pooling of information to a millennial penchant for oversharing, or disapprove of any numerical curiosity on the basis of bourgeois propriety, but if you’re trying to make a living as a writer in 2017, it’s indispensable to know what publications can afford and how much they’re giving your peers. And it’s important to be reminded that, as Malinda Lo puts it, “plenty of authors who appear to be successful in public are, in private, struggling to get by.” “We’re only hurting ourselves as writers by being so secretive about money,” Strayed says before explaining that while her memoir Wild was making the bestseller list, her rent checks were bouncing. (Royalties don’t usually arrive until a year after publication.) In the introduction, Manjula Martin, the book’s editor, writes “writers...are yearning to for any scrap of information they can find about how their own profession functions economically,” and that’s not—or at least, shouldn’t be—normal. Their incomes are less reliable than salaried workers’, but most independent contractors at least have a sense of their industry’s standard.

Those who only obliquely address finances in some ways disregard the spirit of the project. Before it was a book, Scratch was an online magazine run by Martin, the person responsible for the website Who Pays Writers? It’s the only online resource of which I’m aware of that aggregates information about how promptly variously outlets pay and the rates at which they pay. She started it in 2012, a year when it wasn’t safe to assume website contributors were compensated at all; I had many speculative conversations with writing friends around that time about whether a new website was cutting any paychecks or just offering “exposure.” In “With Compliments,” Nina MacLaughlin recalls writing one of these free pieces, a book review that eventually allowed her to sell a book of her own for “a handsome advance.” Yet like many writers, she still feels that “when we agree to volunteer, to have our time and effort go uncompensated...we perpetuate a corrupt and broken system.”

Writers aren’t the engineers of that system, though, and it would be a disastrous mistake to conflate feeding a machine with controlling it. It’s powerful to decide you’ll never write for free, if unsustainable—what, not even a blurb for that dear friend’s debut novel?—but it would be foolish to believe choices about your own time and energy deal a serious blow to The Man (be that Man print media, or online content farms, or the publishing world, or all of the above). Capitalism is older and wilier than we, and if there’s mercy in writing for an outlet that won’t compensate you, it’s the clarity that your only reward is the work itself. Because as so many Scratch contributors can attest, nothing else is ever guaranteed, even when it’s promised. Invoices go unpaid for months or forever; publications fold, pitches are stolen, stories are killed. And part of what’s stressful for writers today isn’t just the uncertainty of the economy at large and ignorance about the going rate for their words but the expectation that they school themselves in more auxiliary skills than ever before; become a self-promoter, secretary, manager, bill collector.

We’re unlikely to garner much sympathy from society at large, since it’s a society that likes having art around yet believes creation of the same should be labor for love instead of labor for profit. But other writers get it, and one of Scratch’s many gifts is this sense of candid communion. “Most writers I know work in a state of perpetual anxiety and self-disgust, and regard the products of their labor as profoundly disappointing,” writes J. Robert Lennon in “Write to Suffer, Publish to Starve.” “Writing is not coal mining. It is merely a pain in the ass, albeit one that tends to invite psychic distress.” One lie new writers often dwell inside is that a byline or a paycheck will quell such distress, but the affirmation of payment and publication verify nothing about the quality of a work. “I was writing for a living,” says Nell Boeschenstein in “Not A Complaint,” “but I wasn’t writing.”

In late 2016, I channeled Rachel Maddux’s “ambition fast” and stopped pitching. The pressure I’d been putting on myself to be published regularly meant my brain was always scavenging for saleable, half-formed ideas, a punishing and neurotic process which has nothing to do with writing as I’ve undertaken it for most of my life. The never-ending search for angles was making me a poorer thinker, poorer writer, and a less happy human.

I mean “poor” here in

the sense of “qualitatively worse,” since the freelancing push that preceded

the fast actually had me earning triple what I had the year before. But there

are a lot of reasons for that increase and they might have come from time as

much as conscientious effort: Expanded connections, a more established “brand,”

greater confidence when negotiating. (I have my candid, incredible circle of

writer friends to thank for these improvements, too.) I grossed a little over

$42,000 last year through the sale of articles and my books. “Gross,” by the

way, means pre-tax and pre-expenses, and the number will be considerably pruned

down after its run through that mill. I don’t think the final figure indicates

anything about how good or bad my writing is, but it does act as further

confirmation that one can make a living as a writer. For me, and for many of my

peers, the question remains: Do I really want to?