At least since Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator, American political discourse has fostered a special genre: the speech of movie actors imitating statesmen and vice versa. Hollywood stars have been lampooning and glorifying and memorializing politicians ever since. At the same time, populist entertainment throughout the 20th century, including radio, defined and redefined the “voice” with which government speaks to its public. Cinema helped develop political rhetoric, its prosody, its timbre, and its vocabulary.

So, Meryl Streep’s presidential address from the Golden Globes podium this weekend felt familiar. When FDR held his fireside chats over the radio, he codified the sound of both the American president and the American patriarch in his castle. Hollywood depictions of the American political voice have been various but contain certain definable strains. In Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, Frank Capra brought an existential sweetness to the Senate, throwing the system into a reassuringly contained and inconsequential chaos as an unknown enters the system by chance (literally, through a coin toss). Similarly, in Forrest Gump the hero accidentally makes an excellent speech about the unmentionable horrors of the Vietnam War due to an unplugged mic. On our televisions, The West Wing fooled us into thinking that grandiose monologues delivered by clever white people could right any wrong in the world.

On television and in movies, mainstream American entertainment defined a very fixed and boring type of president in the late 20th century: a solemn and trustworthy dad to the nation. This type of man thoughtfully knots his fingers across his desk as he announces that a meteor is on its way to earth. Ronny Cox has played a fictional president four times. Morgan Freeman, Sam Waterston, and Roy Scheider have all done it three times. Martin Sheen, of course.

As she accepted the Cecil B. DeMille Award in a big shiny room in Beverly Hills this past weekend, Streep deployed her richest tones to say, “An actor’s only job is to enter the lives of people who are different from us and let you feel what that feels like.” Just as the West Wing performed a fantasy of the halls of power, Streep delivered a liberal fantasy of Trump actually engaging in this kind of political conversation.

She explained that Trump has abused the actor’s power, misappropriated it. He tells the wrong sort of story. In what Streep called a stunning performance, Trump mocked the reporter Serge Kovaleski’s body in a November 2015 campaign speech. The performance “was effective and it did its job,” Streep said. She could not forget it, because Trump’s star turn “wasn’t in a movie. It was real life.”

As if speaking directly to January 2017 from the 1980s, Ronald Reagan rises from his grave to ask Streep: “How can a president not be an actor?” There was nothing unnatural about the performance Trump gave, Reagan says. He was simply leveraging the same resources that are available to all who speak in the public forum. The strange thing really is Streep’s surprise, her horror at the way that Trump has turned the same currency in which she trades (celebrity, speaking in a certain way) into real power.

In our time of celebrity politicians and activist celebrities, it can seem as if traditional roles within the media are blurring, or inverting. Certainly, the distribution of speech among characters within “media” broadly construed is changing. Leftfield nobodies rise through the obscurest websites into positions of serious influence; minor reality television stars become the president of the United States. But public lecturing (and a Hollywood awards show is just that) represents a timeless nexus of entertainment and politics. On screen, in the forum, on the soapbox: Meryl Streep’s speech simply shone light on a small, recent mutation in the ancient genome of speechifying.

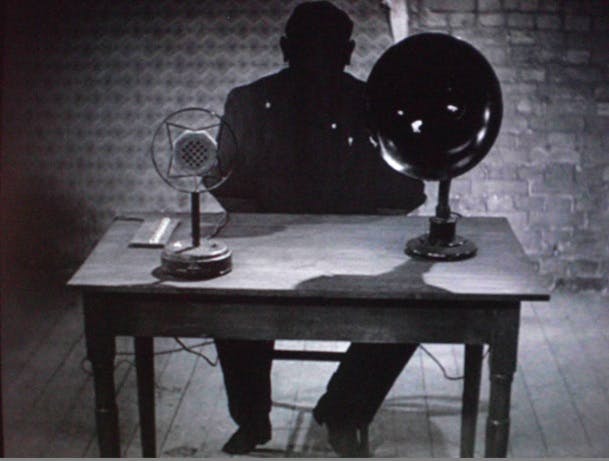

Joseph Goebbels banned Fritz Lang’s movie The Testament of Doctor Mabuse from 1930s Germany. In that film, the terrifying and insane criminal mastermind Mabuse speaks certain phrases that were first used by Hitler. In a key scene, Mabuse is revealed to simply be a voice coming out of a loudspeaker. Goebbels thought that the movie would undermine the public’s faith in their politicians. (The reductio ad absurdum of movies about the voices of power and the power of the voice must be 2010’s The King’s Speech, where the literal sound of words spoken by one the world’s most powerful men became the subject of heart-squeezing drama.)

Streep’s speech was magnificent because “Meryl Streep” signifies magnificence, not because she is. She is gray-haired, and onstage she wore glasses. Her voice is perhaps best described as fruity. She conveys emotion authentically. In a movie from our childhoods about America, Meryl Streep would make a better president of the United States than Donald Trump. In her public politics, she uses the rhetorical vocabulary of America’s glory days, when white tact and white taste and a deep voice and dignified white middle age connoted wealth and power and stability.

In contrast to Streep’s trustworthy, ’90s-style speechifying, Trump speaks the language of the time in which we actually live. His reactions are incoherent but delivered at lightning speed. He has no dignity to place in danger and his face is at home in our ridiculous newsfeeds. In the movies of late 20th century America, he would play a risible villain.

But today, he plays the president. Speechifying turns the voice into a political force. This sounds very obvious, but the examples of Trump, Streep, and Lang together explain that the voice has a special power precisely when nothing is behind it. It suggests that its power is derived from its own charisma or innate properties.

To agree, sadly, with Joseph Goebbels, contests between voices like these undermine the public’s faith in statecraft. In what some have called the “attention economy,” politicians and entertainers compete for eyes and ears. The election of Donald Trump made visible to voters a dynamic that previously only actual rhetoricians (politicians, activists, actors) knew. Sound and fury signify power—and that’s it. That’s why Trump is the president, and Streep is a vision of the type of president we used to believe that we wanted. Political speech has a way of rushing in to fill whatever spaces the media will allow it. Discourse abhors a vacuum. Donald Trump hates it when other people speak.