“I’m just a normal kid,” Erik Menendez says. Across the table, Barbara Walters’s head cranks backwards and her eyelids go all the way up.

“Erik! You’re just a normal kid who ... killed your parents!”

Nodding sadly, Erik whispers, “I know.”

The above exchange is one of many archival gems resurrected by Truth and Lies: The Menendez Brothers—American Sons, American Murderers, ABC’s much-anticipated documentary on Lyle and Erik Menendez, the two rich kids who shot their parents to death in their Beverly Hills home in 1989. As a collection of documents about the way American media covered the sensational murders of the time, the documentary is indeed valuable. But whether it manages to do more than repeat the media’s prurient role is another question.

The first half of Truth and Lies presents their story as a parable of spoiled rich kids gone bad. The case played out in the public eye O.J. Simpson-style, provoking class resentment and fears of moral degradation in the younger generation. The 1993 trial was filmed and broadcast by CourtTV for all to see. And the facts are lurid. On August 20, 1989, Lyle and Erik Menendez blew their parents away with shotguns. It was a warm Sunday night, and many neighbors had their windows open. But nobody called the police, apparently because shootings do not occur in neighborhoods so wealthy and placid. Eventually the brothers called the cops themselves.

At first, they were treated like victims. They had kneecapped their parents, suggesting mafia involvement. The police did not even test their hands at first for gunshot residue. But then Erik and Lyle started spending their inheritance money—supposedly $1 million in the first six months of their orphanhood. Eventually Lyle confessed to his psychologist. When he threatened the psychologist with violence, doctor-patient confidentiality was voided and the evidence made admissible in court.

Once at trial, their defense lawyers did not deny that the brothers had killed their parents, José and Kitty. The attorneys did not deny that Erik and Lyle had inherited $14 million, nor that they had bought Rolexes and cars and invested in restaurants in the days after the crime. They did not deny that they had blown their father’s head completely off, or that the mother had been shot multiple times.

Instead, the defense put forward the argument that the crime was done out of fear, not greed. José Menendez, the brothers testified, had sexually abused them both. Lyle was abused between the ages of six and eight, while Erik was victimized into adulthood. Having told his brother what was going on, Erik supposedly feared for his life, thinking that his father would sooner kill him than let the truth come out. And so, the brothers did what they did.

As a court reporter observes, the brothers were crappy actors. When they denied enjoying Rolexes, they were unconvincing. But as he gave evidence about the objects that his father had used to penetrate his body, and as he apologized to his brother for repeating certain abusive actions on him, Lyle Menendez became difficult to doubt. Otherwise so tranquil, it took Erik Menendez a full red-faced minute to say out loud that his father had molested him.

The 1993 case ended in mistrial. At the second trial, however, the judge excluded evidence of the family’s past. The brothers were sent to jail for the rest of their lives.

There are certain nuggets of information in this documentary that are as puzzling as they are horrible. The family kept ferrets, one family friend recalls. A ferret died one day. Everybody assumed the dog did it. The children opened the refrigerator one day and found the dog’s head inside. No further exegesis is given. A talking head comes on the screen to report that Kitty Menendez once ripped Lyle’s toupée from his head during a fight: the revelation of his baldness spurred Erik to confess the secret of his father’s abuse.

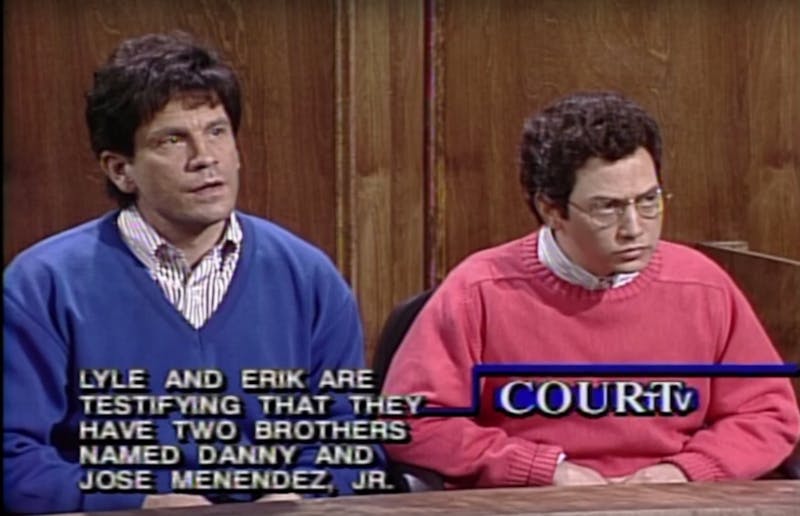

Throughout all this, ABC repeats the media choices that turned the Menendez brothers into grim Californian celebrities. Although another talking head is shown condemning the way that Erik and Lyle’s testimony of abuse was turned into literal SNL skits, the show’s silly collaging effects (a headshot of Madonna to signify the mid-1980s, a headshot of Johnny Depp to signify the early 1990s) and its slogan (“American Sons, American Murderers”) do nothing to turn these sad men back into human beings.

In some ways, Truth and Lies is a testament to entertainment media’s remarkable ability to produce newly textured takes on old stories for decades on end. This documentary sutures fascinating testimony from the first trial’s prosecutor with a bizarre recollection from a family friend who watched that trial with his “dalmatian puppy.” Bright flashing colors stand in for narrative structure. The legal questions at the heart of Truth and Lies continue to be compelling. As a piece of television, however, one can only repeat the SAT-synonym word-pile Erik Menendez gave when Barbara Walters asked about his relationship with his father: “Brutal. Painful. Torturous.”