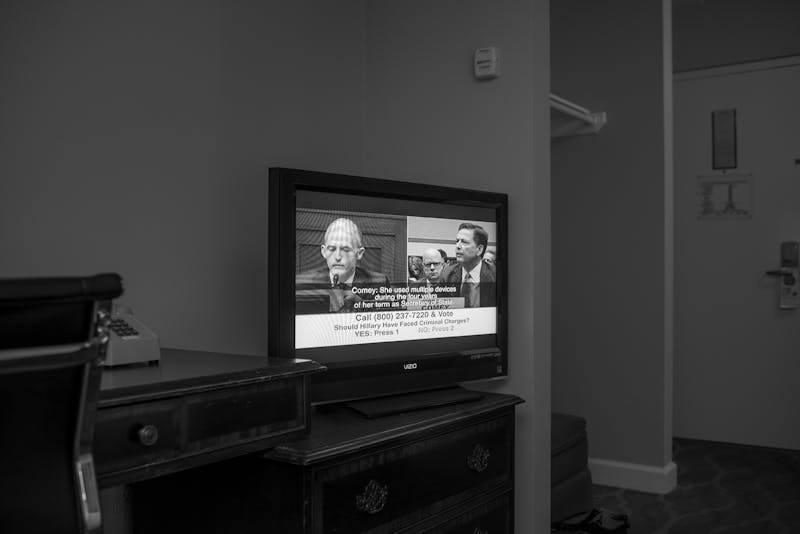

Global conspiracies, secret dossiers, Russian hackers, terrorist plots; if the United States seems like it’s experiencing a nationwide panic attack right now, its most fervent hyperventilations might be best observed in Washington, D.C., where power and paranoia live in close proximity, reinforcing one another’s potency.

“I don’t think I’d be alone in saying there’s kind of a collective meltdown taking place,” says Austin-based photographer Mike Osborne, whose series White Vans & Black Suburbans serves as a kind of funhouse mirror for this sensation, reflecting the nation’s psychosis back on itself in a manner that’s by turns amusing and disturbing. Osborne moved to D.C. to teach at Georgetown University in 2012, but didn’t start taking photos in the capital and the surrounding area until two years later. Once, as he set up his tripod in a Crystal City parking lot to photograph a nondescript building he’d noticed near Reagan Airport, two camouflaged security officers confronted him. Did he know he was on government property? Did he know that his car, had it been laced with explosives, could bring down a nearby hotel, and by extension, the building they were guarding?

This intersection of banality and hostility would come to characterize many of the photos Osborne has made since: Dick Cheney’s cookie-cutter house in McLean, Virginia, sits silently and serenely in the snow; a long, dark road to a Russian Embassy compound in eastern Maryland—recently shut down as part of the Obama administration’s retaliation for the country’s alleged interference in the presidential election—is made mysterious by the glare of headlights. And then there are the white vans and black suburbans, as ubiquitous in the city as they are anonymous—one is the impenetrable transport of the powerful, the other, a vehicle commonly used by tradespeople. Or rather, is one used for espionage, the other to deliver a bomb? In Osborne’s renderings, the implication is intentionally ambiguous. “These moving vehicles are a kind of question mark for these two very different kinds of phenomena,” Osborne said. “I like that sort of slipperiness, the way a thing, by its unknowability, becomes a projection.”

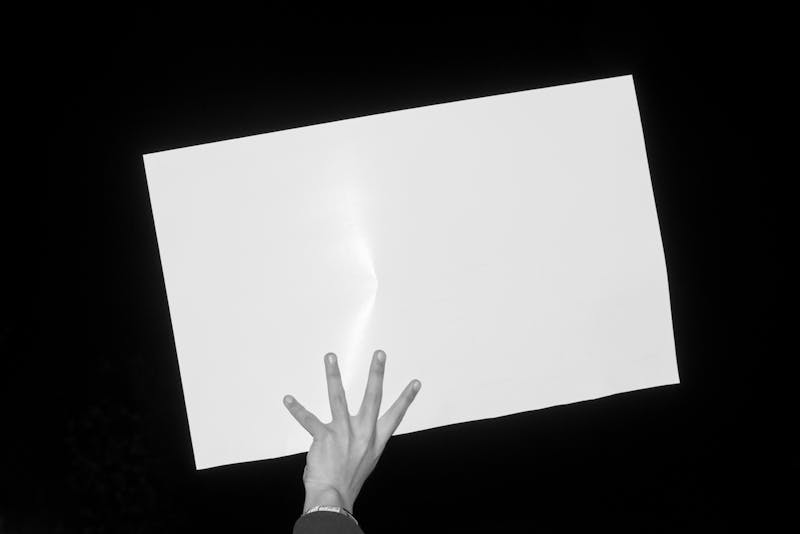

Like Trevor Paglen and John Gossage, Osborne uses his camera to capture the all-seeing eye of the state. Snapping away near CIA headquarters, or at an office park housing NSA contractors, he looks back at the people who look at us. His frames are populated by the usual cast of DC regulars—activists, pedestrians, the occasional government worker or congressman—pictured either in solitude or in large clusters, in a landscape whose black-and-white flatness adds to a pervasive sense of anxiety.

Osborne has done all of this, mind you, without press credentials, often in locations where photographers are already seen as unsavory, at best. In times like these, that makes Osborne something of a suspicious character himself. But Osborne doesn’t mind. In fact, he kind of likes it. “It’s slightly uncomfortable making these kinds of photographs,” he says. “That’s something I’m interested in, that place of unease or discomfort.”