I read an interview with Chris Rock a few years ago right after Joan Rivers died. “The compliment you give of a comedian,” he said, is: “Who wants to follow them onstage? Nobody wanted to follow Joan Rivers, ever.” Even in her 80s, Rivers was testing her material in small clubs a few nights a week in New York City, hawking her jewelry on QVC, and keeping a schedule that would exhaust a person half her age. She never told a stale joke—when her Liz Taylor material got old, she moved on to Lindsay Lohan, then Kim Kardashian. No one was safe. Rivers was a brutal truth teller, someone who shakes up the status quo by skewering important things—everyday sexism, casual ageism, manifold other forms of inequality—and leaving destruction in her well-heeled wake.

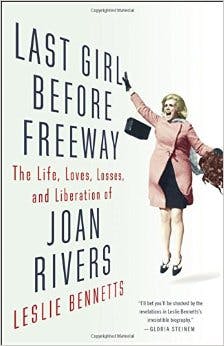

The arrival of the first major biography of Rivers, Leslie Bennetts’s Last Girl Before Freeway, means it’s time for some reckoning with Rivers’s ambivalent feminist legacy. Rivers set the bar extremely high for female comics, was never particularly gracious to other women in the business, and was not the type to reach down with a helping hand for a younger woman (quite the opposite, she always saw them as threats).

Rivers never quit, which is rare for comedians, most of whom retreat from the public eye once they become successful (Rock, Seinfeld, etc). She worked like a dog for her entire sixty-year career. It’s too soon to tell whether that will be true about all of the female comics who have benefited from her trailblazing: Kathy Griffin, Lena Dunham, Sarah Silverman, Amy Schumer, Abbi Jacobson and Ilana Glazer, and many others. (I’m cherry picking mostly Jewish females but could argue that gay and lesbian comics and other minorities like Rock also built on Rivers’s legacy). Rivers changed the establishment from within, which is the hard way: She just kept talking and the people kept laughing, and eventually the world caught up.

Though there were female comedians before her, none of them had the superstar status Rivers did. She was never beautiful, which she knew, and she parlayed her funny looks into a funnier and deeper role: Because she was a woman who did not get the special treatment reserved for the beautiful, she told the truth about how men treated women. It was not pretty, but we accepted that she was telling the truth. When, in her 60s, she joked that a gray bunny slipper looked like her vagina, which had dropped during menopause, we laughed because it’s gross but honest, and because it’s pure Joan.

Joan Rivers was born in 1933 in Brooklyn, though once she started doing stand up she was quick to tell audiences she was from the tony Westchester suburb of Larchmont, New York, “Where if you’re not married, and you’re a girl, and you’re over twenty-one, you’re better off dead.” In Bennetts’s telling, Rivers’s story is about a Brooklyn girl who makes good. As “the ugly duckling who helped to change the world,” her work was, “fueled by the anger she wasn’t beautiful.” This is a valid argument, borne out by her obsession with plastic surgery and her significant history of eating disorders (she would order a lettuce leaf and eat Altoids while out to dinner with friends, sometimes sipping at a glass of white wine). In her act Rivers also raged about beautiful women, particularly her childhood idol, Elizabeth Taylor, who was the victim of some of River’s meanest jokes after she gained weight in the 1970s.

She encountered, however, many greater obstacles than beauty. When Bennetts starts her book, Rivers is at her lowest point: Her husband of 23 years, Edgar Rosenberg, has committed suicide and left 55-year-old Rivers, whose late night talk show on Fox had just failed, a Hollywood pariah. Oh, and she was also $37 million in debt. Bennetts locates this as the place and time when Rivers took control of her life, figured out how to make and manage money (previously Edgar’s job as her manager), and generally hustle for jobs, any job. Rivers didn’t collapse into her chintz sofas and cry like some soap opera diva. She got on the phone with her agent and told him to book her anywhere: Find her a gig and she’d take it. She knew she was poison on late night—Johnny Carson had put a hex on her appearing on any late night shows, which lasted until Jimmy Fallon had her as a guest in 2014. But Rivers would try anything—and did—for a buck, especially in this low period.

Rivers’s work ethic and hustling instincts were already honed by the time of Edgar’s suicide in 1987. She was already moving on with her career. She was thinking of separating from Edgar, whose clinical depression was becoming too much for her to handle. Rather than Bennetts’s narrative of an ugly duckling desperately trying to become a swan, I’d posit that Rivers was forever trying to live out her childhood dream of becoming a serious actress. The greatest moment of Rivers’s childhood was playing the pretty kitty in a pre-kindergarten play. Rivers longed to recapture that feeling of being beautiful and loved, of having the world declare her a pretty princess. But Rivers was clever: She knew actresses took on many roles, and pretty princess would just be one of hers.

How many roles did Rivers play throughout her life? Here’s my count. There was the founder and savvy head of her QVC empire, a sharp business woman who never left the house without wrapped gifts from her costume jewelry collection for whomever might do her a solid turn: a nurse, an assistant, a maitre d’. Before the QVC years there was the devoted wife, who left all business matters to her husband, which turned out to be a huge miscalculation. There was the loving, smothering, cajoling, Jewish mother, who existed from the moment her daughter Melissa Rosenberg Rivers was born in 1968.

Especially after Edgar killed himself and her daughter’s marriage ended in divorce, Joan and Melissa were partners in business and in life, inextricable and emotionally bound. Even as both dated men they remained each other’s primary partners, raising Melissa’s son, Cooper, and building part of Joan’s business together. That business was E!’s Fashion Police, which put Joan in the role of the red carpet maestro, the fashion commentator with no training but her own taste (which, arguably, women had come to trust because of her QVC line and her posh wardrobe on her daytime talk show, which aired from 1989 to 1993).

Of course, also after Edgar’s suicide and her move from Los Angeles to New York City there was Joan the quasi-socialite, who had a renovated ballroom decorated like Louis XIV and palled around with Nancy Reagan, Betsy Bloomingdale, and even Prince Charles and Camilla. Rivers’s pal Blaine Trump (ex-sister-in-law to the president elect) said, “The English all have potty humor, and Joan was full of that kind of humor. They loved it, and they were real friends.” She even met the Queen, which delighted her to no end. Rivers loved being around power and status; her politics were quite conservative with the exception of LGBTQ rights and reproductive rights.

All along she remained the lewd standup comic, for whom nothing was sacred: not her sex life (or lack thereof), or her husband’s suicide, or aging, or the flaws of others. This Joan gets progressively angrier and nastier, there’s no mellowing with age for her. Scratch the surface, though, and you’ll find Joan the fabulous hostess, very concerned with manners and propriety, setting out finger bowls and serving holiday dinners (which she did not cook, but catered, yet still) all to perfection. These were but a fraction of Joan’s roles and she slipped in and out of them without thinking, like changing into a glamorous jacket (she had a penchant for statement jackets with feathers and glitter) before a late show.

In her capacity to shapeshift, Rivers was able to influence a broad swathe of the entertainment world we live in today. Fashion Police spawned a host of imitators and Joan’s signature question: “Who are you wearing?” launched an impressive number of magazine front-of-the-book features. Both Fashion Police and its competitor shows focused on the Oscars and other award shows as well as your run-of the-mill film and TV premieres. Bennetts also describes the rise of the celebrity stylist and argues convincingly that we have Rivers to thank or to blame for the likes of Rachel Zoe. She cites the wonderful 2010 documentary Joan Rivers: A Piece of Work, in which Rivers reminisces about how fun it was in the days before actresses had stylists; back then, the stars could actually explain why they chose what they wore to an award show with some personal anecdote, or, even funnier, without any reason at all. Once a stylist like Zoe enters the frame, the personal is evacuated and everything from the dress to the manicure is just a business transaction, “My stylist blah blah blah.”

Before Rivers made the red carpet a commercial venture, there was no such thing as a mani-cam or endless questions about designers and jewels to make the red carpet the designer showplace it is today. Bennetts also shrewdly sees Rivers as the forerunner of the internet denizens who police everyday women’s bodies online now. “It would be impossible to quantify the cumulative impact of Rivers’ nasty commentary,” she writes, “but the trends it encouraged undoubtedly helped to normalize the sexist cruelty that has become standard far throughout popular culture.” Not only do we now routinely subject women “to various criticism of every aspect of their appearance” but we have also made all forms of public engagement more difficult for them. “For female public figures of any kind, venturing an opinion can instantly elicit horrifyingly misogynist threats of rape, dismemberment and other harrowing forms of death from an army of trolls,” Bennetts notes ruefully.

It seems hyperbolic to me to put trolling on Rivers, and yet I do see Bennetts’s point. By bringing to television and then quickly to tabloids the idea that someone wore it best and that the red carpet is a gladiator-level contest (with competitions for the best jewels, manicure, shoes, etc.), Rivers did start a phenomenon that has turned into a frightful, insatiable beast demanding nothing short of perfection from women. I do not want for Rivers to be the ancestor of internet fat-shaming, yet she did not do anything to encourage body acceptance either. She lived in a world of high standards and breath mint dinners, and did not hesitate to apply her own harsh standards to others.

Rivers’s legacy is complex. She could be absolutely vicious about younger comics, though sometimes she’d help them despite her curmudgeonly ways. She’s wonderful playing herself on an episode of Louie that captures this contradiction: She starts out characteristically nasty to him but ends up surprisingly maternal and tender. On her reality show, Joan and Melissa: Joan Knows Best?, she was a mentor to Tony, the head writer on Fashion Police and a standup comic, and positively lovely to her staff and her many friends. She’s an easy laugh—one can see how she attracted so many friends. While hanging out with a lot of comics seems like it would get tiresome (it’s funny to watch, but do you really want to get into Jerry Seinfeld’s car with your coffee?), Rivers doesn’t feel like she’s trying out material all the time. She’s a hoot, a smart, funny, overdressed, irascible Jewish lady you’d love to have a drink with (especially at a gay bar).

When she’s onstage, though, she is fierce, and that seems like an attitude a lot of female comics have borrowed from her. To be taken seriously as a comic, you have to be serious and always on your grind. There are no female Steven Wrights for a reason. To be a female comic you have to be better than the men. You have to tell better jokes, have better delivery, better timing, better put downs against hecklers, and a thicker skin for when club owners try to screw you over or fellow comedians try to put you down. Rivers was an example of that: No one could top her, and as Chris Rock said, no one wanted to follow her either.

Rivers’s death was an accident which suspiciously sounds like a downside of her participation in so many plastic surgery procedures, or as she would say, FFF or “flashing the famous face.” She was scheduled for a routine upper endoscopy to examine her throat at her ENT’s office. This ENT also served as her GP, and did many of Rivers’s routine procedures at her office. She was not in the office for this one and there were complications the staff could not handle. Rivers ended up getting rushed to a hospital, where she was put in a medically induced coma from which she never woke up. She died on September 4, 2014. Melissa Rivers has filed several lawsuits which are still in court, including a wrongful death suit.

When she was alive, Rivers cut off all talk of her being a role model. “Stop talking like I’m not here,” she’d say in A Piece of Work if someone asked about Kathy Griffin or Amy Schumer or Lena Dunham. Now we can talk for hours about the people she inspired or influenced, but it’s not as much fun as having Rivers around. One role model is sometimes worth a whole roomful of imitators.