Specialist Nicolas Plantiko burned dogs. Sergeant Thomas J. Brennan burned lithium ion batteries, flame-resistant FROG suits, and MK-19 rounds. He burned plastic chemical drums, nylon, tires, wires, and tarps. He burned shit and piss. Sergeant Bill Moody’s unit burned a Porta-John, dried-up MREs, and 500 loaves of moldy bread. Staff Sergeant Louis Levesque burned bunk beds. Private Johnnie Stevenson burned plastic bottles because he loved the way they hissed. Airborne infantryman Dennis St. Pierre burned radio batteries and chemlights. Sergeant Carlos Castro joked about burning another soldier for talking too much. Captain Matthew Frye burned a packet of Tabasco sauce that exploded and nearly took out the JTAC’s eye. Staff Sergeant Tim Wymore burned 25 loads of DEET-soaked tents and walked around with the taste of smoke in his mouth. Sergeant Zachary Bell burned batteries because the Taliban used the carbon rods for IED triggers. Specialist Dante Sowell burned burlap bags so he wouldn’t have to fill them up with sand. Captain Adrian Bonenberger watched a Christmas tree go into a burn pit. Private George Snyder burned Private Stuart Decker’s one confirmed kill. Sergeant Casey Rohrich burned a human toe. They burned magazines, movies, junk food, college brochures, and pamphlets for the GI Bill. They burned amputated body parts and Humvee parts. They burned human waste and plastic meal trays. They burned the blood and clothes of the wounded.

Everything—all the trash of the war—was thrown in a burn pit, soaked with jet fuel, and torched. There were hundreds of open-air garbage dumps, spread out across Afghanistan and Iraq, right next to encampments where American soldiers lived and worked, ate and slept. The pits burned day and night, many of them around the clock, seven days a week. There were backyard-size pits lit by patrols of a few dozen men, and massive, industrial-size pits designed to incinerate the endless stream of waste produced by U.S. military bases. Camp Speicher, in Iraq, produced so much trash that it had to operate seven burn pits simultaneously. At the height of the surge, according to the Military Times, Joint Base Balad was churning out three times more garbage than Juneau, Alaska, which had a comparable population. Balad’s pit, situated in the northwest corner of the base, spanned ten acres and burned more than 200 tons of trash a day.

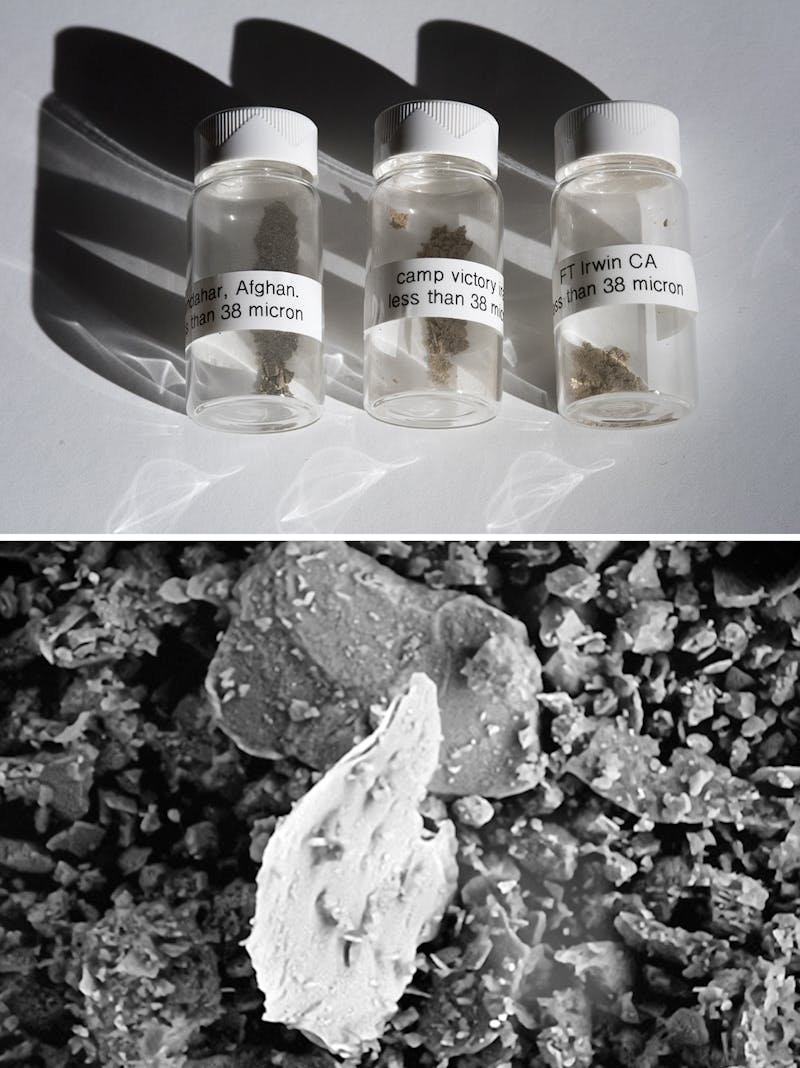

Much of the waste in the pits was toxic, and burning it released a lethal array of pollutants: particulate matter, volatile organic compounds, hydrocarbons, neurotoxins. JP-8, the jet fuel often used to ignite trash, released clouds of benzene, a known carcinogen. One analysis conducted on dust samples from Camp Victory in Iraq found hazardous levels of copper, iron, and titanium particles. Other researchers detected dioxin, the cancer-causing chemical found in Agent Orange. Burning plastic bottles released dioxin and hydrochloric acid, and burning foam cups released dioxin, benzene, and other carcinogens.

“Ash spread over everything,” Leon Russell Keith, a military contractor who was stationed at Balad, testified at a Senate hearing in 2009. “Our beds, our clothing, the floor.” Thick black smoke poured into the barracks. The air conditioners blew ash. Ash stained the bed sheets. Their teeth turned black from the soot. Ash rained down on the men, on the American troops, the Iraqi detainees, the Iraqi correctional officers. One soldier described the smoke as thick “like San Francisco fog.” Another called it “pollen dust.” The color of the smoke changed depending on what was burning that day. It could be blue and black, or yellow and orange. Mostly it was black. Everyone inhaled it. They ingested it. It was on their skin.

The burn pits were supposed to be temporary, an imperfect stopgap required by the exigencies of invasion and occupation. But like much of the war, the burn pits were privatized, the military’s trash turned into a lucrative, for-profit enterprise. Kellogg Brown & Root, which operated the burn pits as part of a $35 billion logistics contract in Afghanistan and Iraq, went on burning waste in open-air pits for years, even after the government dispatched cleaner-burning incinerators to U.S. bases. The military was aware that the burn pits posed a risk to soldiers. “There is an acute health hazard for individuals,” an Air Force bioenvironmental engineer warned his superiors in 2006.

It didn’t take long for soldiers to begin to fall ill. As early as 2004, veterans who had served near burn pits began complaining of a complex and enigmatic constellation of symptoms: asthma, sinusitis, bronchitis, unexplained diarrhea, persistent runny nose or cough, severe headaches and abdominal pain, ulcers, weeping lesions on the extremities, chronic infections. Many coughed up black mucus, which they called “plume crud,” “black goop,” or “Iraqi crud.” Some developed cancers—tumors grew on their lungs, brains, bone, and skin—including leukemia. Others suffered from severe respiratory conditions, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and constrictive bronchiolitis, a rare and often fatal lung disorder for which there is no treatment.

Rick Lamberth, an Army Reserve lieutenant colonel, worked for Kellogg Brown & Root in Iraq and Afghanistan from 2003 to 2009. Lamberth suffers from rashes, spits up bloody mucus, and has shortness of breath. Shortly after returning home, he testified to a panel of Democratic senators about how KBR operated the burn pits. “From as close as ten feet away,” he said, “I saw nuclear, biological, and medical waste—including bloody cotton gauze, plastics, tires, petroleum cans, oil, and lubricants—thrown into burn pits.” One government investigation found that KBR ignored military regulations designed to protect soldiers; another found that the company systematically hid what it was doing, refusing to share “proprietary” information on its procedures with the military. Lamberth testified that when he tried to report violations, his supervisors at KBR ordered him to “shut up and keep it to myself.” If he went public, they warned, the company would sue him for slander.

As the burning continued, more and more soldiers got sick. Sergeant Zachary Bell, a marine rifleman who served in Afghanistan from 2007 to 2010, suffers from painful welts all over his arms. Sometimes his hands go numb, or he breaks out in rashes, or he goes into full anaphylactic shock. When he went to Veterans Affairs, the doctors gave him pain pills, sleeping pills—500 mg of Hydrocodone, Valium, and Ambien. All his friends from the war have unexplained illnesses. Everyone suffers from chronic pain. Many have been unable to work. Some of them cough up black stuff. “A few of them have the skin thing, too,” Bell tells me. He sometimes rolls up his sleeves to show people his welts. “It’s a crowd pleaser,” he says.

In most cases, when veterans have sought treatment or disability benefits from the VA for exposure to burn-pit smoke, their claims have been rejected. The Defense Department maintains that there is no proof that the burn pits made soldiers sick. Troops in Iraq and Afghanistan were exposed to a host of environmental hazards: There were toxic particles in dust and sand, chemicals in fuel and exhaust fumes, industrial accidents and sulfur fires. From a purely diagnostic standpoint, ailing veterans could have been injured by any one of these factors, or a combination of them, or none of them at all. By 2010, at least six years after soldiers began falling ill, the Defense Department was still assuring Congress that open-air burning was “the safest, most effective, and most expedient” means to dispose of military trash in a combat theater.

What is happening with the burn pits follows an all-too-familiar pattern of official dishonesty and deception that has been repeated in war after war. First comes denial: The VA didn’t acknowledge the damage caused by Agent Orange until 1991, nearly two decades after combat troops withdrew from Vietnam, and for years it dismissed the neurological condition known as Gulf War syndrome as psychosomatic. Then, once veterans begin to protest, the military agrees to “study the problem.” Next, it stalls for as long as possible: Long-term studies are commissioned—some of which can take decades. And finally, the government manipulates the outcome to reach the desired conclusion: that there isn’t enough data to confirm a correlation between the illness and its apparent source. Again and again, from Saigon to Kabul, the government has designed inadequate studies, manipulated data, and ignored relevant academic research, all to avoid responsibility for the harm done to our soldiers. Their illnesses linger and worsen. For some ailing veterans, the delay effectively serves as a death sentence.

“It took the government years to recognize that there was a link between Agent Orange and the devastating health effects on our soldiers,” Senator Amy Klobuchar, a Democrat from Minnesota, and Senator Thom Tillis, a Republican from North Carolina, observed in an op-ed for Fox News in May. “Veterans had to wait to get the care they desperately needed and clearly earned. Today we have a new Agent Orange: burn pits.”

Senior Master Sergeant Jessey Baca was in his mid-forties and in good health before he served two tours in Iraq. He liked to run—he did a half-marathon once—and to raise green chilies in his garden in Albuquerque. He’s been married for 38 years and has two children and four grandchildren. On his first tour, in 2004, he spent six months at Balad, as an aircraft maintenance technician for the New Mexico Air National Guard. He worked, ate, and slept near the burn pits. “The smoke was blue and knee-deep, like a fog,” he says. “I had to dust myself off from all the ash falling on me.”

After his first tour, he began suffering from flulike symptoms and upper respiratory problems. His doctors in Albuquerque told him he had a cold. Baca had fevers that wouldn’t go away, cold chills and night sweats, a persistent cough, and blood in his mucus. The doctors subjected him to a battery of tests, all of which came back inconclusive—“their favorite word,” as Baca puts it.

In 2007 he passed his deployment physical and returned to Iraq, again at Balad. This time, his health got much worse. He spent part of his tour on bed rest. At one point, he noticed a spot on his nose; every time he touched it, it would bleed. After he got home, he suffered from massive headaches, chronic fatigue, and hearing loss. He had trouble breathing. He was diagnosed with basal cell carcinoma, three layers deep into his skin. There were lumps on the side of his face below the jawline. His body hair fell out. His hands swelled and developed lumps, which turned out to be tumors.

At the VA in Albuquerque, the doctors told his wife, Maria, that Jessey had post-traumatic stress disorder. “PTSD doesn’t cause tumors,” she replied. “It doesn’t cause coughing up blood. It doesn’t cause bronchitis.” She was informed that her reaction was part of the problem. “It’s wives like you that cause soldiers to commit suicide,” a VA staffer told her. “Because you won’t admit they have PTSD.”

Baca never denied he had PTSD. “But, you know, I also had tumors,” he says.

Baca went from one VA to the next, one doctor to the next, test after test, hoping for an explanation. He ticks off the list: “MRIs, CT scans, X-rays, vials of blood, and more blood.” He saw pulmonologists and rheumatologists, infection specialists and internists, orthopedists. They could find his sickness—it was everywhere—but they couldn’t tell him what was causing it. The VA denied that his ailments were service-related, so he was forced to pay for a lot of the treatment out of his own pocket. The VA also denied him disability, so he kept on fixing airplanes, even as it became hard to walk or breathe.

Finally, a doctor at National Jewish Health in Denver referred him to Robert Miller, a pulmonary specialist at Vanderbilt University who had conducted a study on veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan with post-deployment respiratory problems. Like Baca, many of the soldiers had been exposed to the burn pits. When Miller did biopsies on the vets, he found that a high percentage of them had constrictive bronchiolitis, an incurable and often terminal illness. “It’s an untreatable disease,” Miller said at the time. “We don’t know what’s going to happen to these people down the road.”

In 2009, Jessey and Maria arranged to visit Miller in Nashville. But before they left, they learned that their insurance wouldn’t pay for the visit because it was out of network. Baca went to Vanderbilt anyway. Miller did a lung biopsy. The results were as Baca feared: He had constrictive bronchiolitis. He was going to die.

But he also felt a sense of relief. With a diagnosis, he could finally receive disability benefits. It took three years for his first claim to be granted. By then, he and Maria were exhausted and nearly broke. All told, they had paid more than $200,000 for private insurance. When they needed airfare to visit specialists, they had to ask a group called Angel Airlines for Veterans to pay for the ticket. “We should be able to seek the treatment we needed without begging for help,” Maria says.

Maria didn’t want other veterans to have the same experience, so she looked around online for a place to let them know about Miller’s research. She came across a Facebook page called Burn Pit, where veterans and their families shared stories about doctors and the VA. Maria posted a message about Miller’s research on the page.

“I didn’t expect a response,” she says. “But I was flooded with messages from vets who were fed up with the VA and wanted diagnoses for illnesses they believed were caused by burn-pit exposure.”

To help spur action, Maria decided to start her own Facebook page, Burn Pit Families. Nine veterans and their families replied to Maria, and they began working together. Staff Sergeant Tim Wymore, who served at Balad in 2004, had lost most of his colon to a bacterial infection. He suffered from a host of severe illnesses, including constrictive bronchiolitis, as did Captain Le Roy Torres and Sergeant Aubrey Tapley. Sergeant Bill McKenna had stage four lymphoma. Steven Ochs, an Army paratrooper, and Matthew Bumpus, an Army staff sergeant, had died recently of acute myeloid leukemia, a rare and aggressive form of cancer. Kevin Wilkins, a registered nurse in the Air Force Reserve, had also died of a rare brain cancer after serving at Balad. He was represented by his wife, Jill, who had started the Facebook page Maria used.

In 2009, Baca joined other veterans and military contractors who filed a lawsuit against KBR for negligence and “willful and wanton conduct.” KBR has denied responsibility, insisting that it operated burn pits “safely and effectively.” The company also tried to have the lawsuit dismissed, arguing that it had “derivative sovereign immunity,” which means it couldn’t be sued because it was acting as an extension of the U.S. military. Last year, however, the Supreme Court declined to review the KBR case, which has grown to 800 people, allowing the lawsuit to go forward.

On the legislative front, Jessey and Maria worked with Senator Tom Udall, who drafted a bill calling for the creation of an official registry for burn-pit patients. This was the same pattern that the government had followed when veterans began suffering from mysterious health problems after the Gulf War: beginning the arduous process of assembling a list of those who had been exposed. Jessey and Maria traveled to Washington at their own expense to support Udall’s bill, which Congress passed in 2012.

The registry did not guarantee medical treatment or disability payments to veterans who had been exposed to burn pits. Instead, it was established only to gather information “necessary to ascertain and monitor the health effects of such exposure.” In short, it committed the government to study the problem. After another two years of delays, the registry opened in June 2014. More than 90,000 veterans have registered.

Baca calls the registry “a milestone for veterans” that “brought awareness to the issue, like with Agent Orange.” But in the two years since the registry was created, little has changed. In January, Stars and Stripes reported that the U.S. military was still using a burn pit to dispose of medical waste at the al-Taqaddum Air Base in Iraq—years after the government required the use of incinerators. And in March, Senator Klobuchar introduced a bill that would require the VA to create a national “center for excellence” for the “prevention, diagnosis, mitigation, treatment, and rehabilitation of health conditions relating to exposure to burn pits.” According to GovTrack, an independent organization that monitors congressional legislation, the bill has a 1 percent chance of being enacted.

On its public health web page, the VA has posted a terse, official statement about burn pits. “At this time,” it reads, “research does not show evidence of long-term health problems from exposure to burn pits.”

This statement is untrue, in the way that official statements are often untrue: not because it contains an outright lie, but because it twists the meaning of everyday words like research and evidence.As the VA knows, there has, in fact, been significant research into burn pits by reputable scientists at established academic institutions, who have published their findings in major, peer-reviewed publications. And that research strongly suggests that long-term health problems among veterans may well have been caused by exposure to burn pits.

One of the first studies was conducted by Miller, the professor of clinical medicine at Vanderbilt. In 2004, soldiers from the 101st Airborne returned from a one-year deployment in Iraq and were stationed at Fort Campbell, not far from the university. Some were so short of breath, they were unable to complete the Army’s two-mile run—one of the military’s most basic tests for physical readiness to deploy. Physical readiness is an important factor in determining “service connection,” the causal link for military-related illnesses that obligates the VA to provide medical care or disability benefits.

A soldier who has completed a tour of duty was, by definition, physically fit prior to deployment. So when healthy soldiers are suddenly unable to complete the same test they passed prior to deployment, there is a baseline indication that something happened to them during their service that caused their health to deteriorate. As Miller later recalled, what each soldier told him was remarkably consistent: “I was elite. I was athletic. I was deployed. And now I can’t do my two-mile run, and I’m not deployable.”

Miller’s study was published in 2011 in the New England Journal of Medicine. In a related paper, he observed that constrictive bronchiolitis “rarely occurs in otherwise healthy and athletic individuals. It is known to result from toxic inhalation.” He also noted that researchers at National Jewish Health in Denver found similar patterns of constrictive bronchiolitis among soldiers exposed to burn pits.

Other academic researchers were also studying how burn pits had injured soldiers. In 2004, Anthony Szema, an occupational medicine and epidemiology expert at Hofstra, noticed a sudden shift in the kind of patients who came to him for treatment. “Before, I mostly saw 80-year-old veterans,” he recalls. “Now I saw young women and men, previously healthy soldiers, who were out of breath and suffering respiratory illnesses, including asthma, and no longer fit to deploy.”

When asthma medication didn’t improve their conditions, Szema began conducting a series of tests to figure out what was wrong. He acquired three sets of dust samples: one from sand taken from the San Joaquin Valley in California; another from a titanium mine in Montana; and a third from a burn pit at Camp Victory in Iraq. When Szema pumped the samples into the lungs of laboratory mice, the result was striking: Mice that inhaled the Camp Victory dust suffered the highest levels of lung inflammation and suppressed T-cells, which form the core of the body’s immune system. The study was published in the Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine.

While Szema’s sample size was tiny—only 13 mice—the results matched what he saw among the soldiers he treated. “Humans are not supposed to breathe in particles,” he says. “If we breathe in high concentrations of particulate matter, we will suffer prematurely, of lung disease or asthma, regardless of where the particles are coming from. Humans should not be inhaling smoke. We should not be burning trash. In Iraq, the trash is fueled by jet fuel. Do you want to breathe jet fuel?”

Szema compares burn-pit exposure to the illnesses suffered by firefighters, police, and other 9/11 workers after the collapse of the World Trade Center. “The exposure is much worse in Iraq,” he says. “Not only were many of these guys deployed for a whole year, but in addition to burn pits, there are tons of other exposure sources. It’s a multifactorial issue. If you’re not dead after the Humvee explodes, then you are going to breathe in bits of the vaporized Humvee. Whatever they aim at you over there, it blows up. Then you head back to base after battle and hang out and breathe in all the smoke from trash fires, because the smoke was in the mess halls and bathrooms and barracks.”

The issue of multifactorial exposure is at the heart of the battle over burn-pit disabilities. Because troops were exposed to so many health hazards, from sandstorms to IED blasts to mine fires, it is extremely difficult—if not impossible—to isolate a single cause behind a rash of ailments with absolute certainty. But for many soldiers, Szema notes, the burn pits delivered a steady stream of toxic chemicals straight into their lungs, day and night. “The lungs are our body’s filters,” he says. “Go to Iraq and your lungs are like the back of an air conditioner you haven’t changed for five years. It’s like Iraq is coming out of their lungs.”

The government’s response to these studies has been emblematic of its past approach to service-related illnesses among veterans. First, it sought to debunk the early research. Then, it manipulated its own studies to ensure that the outcome would arrive at the word so many burn-pit soldiers have come to dread: inconclusive.

In 2009, the VA commissioned a major study of burn pits, focused on the Balad base. The study was conducted by the Health and Medicine Division—previously known as the Institute of Medicine—at the National Academy of Medicine. HMD’s mission is to “provide independent, objective analysis” that will help “solve complex problems and inform public policy decisions related to science, technology, and medicine.” In practice, however, HMD faces the same pressure any other consulting organization faces: to produce results that will please its client. More than half of all funding for HMD and the National Academy of Medicine comes from the federal government, including 13 percent from the VA. The HMD study on burn pits, in short, was underwritten by the very agency potentially facing billions of dollars in insurance claims from veterans exposed to burn pits.

In 2011, after two years of study, HMD issued a report entitled “Long-Term Health Consequences of Exposure to Burn Pits in Iraq and Afghanistan.” The report wasted no time dismissing the “concerns” expressed by ailing veterans. The public furor, it suggested, had been created by “articles in the popular press” and “anecdotal reports.” Such reports, HMD warned, “do not demonstrate causality or even association; the committee looked instead to the epidemiologic literature on the exposed populations, and on populations similarly exposed.”

HMD’s own conclusion amounted to one big scientific shrug. Its researchers reported that they were “unable to say whether exposures to emissions from the burn pit at Joint Base Balad have caused long-term health effects.” They conceded only that service in Iraq and Afghanistan “might” be associated with long-term health effects. They also recommended further study—not of burn pits, but a “broader consideration of air pollution.”

A closer look at the study, however, reveals that the HMD shaped the methodology and data to avoid linking burn pits to the widespread suffering among veterans. The research protocol it followed required a “risk assessment process” for contamination that was first developed by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission in 1983. The process sounds straightforward enough: First, you study the contamination level of a specific place, such as Balad. Then, you figure out the inherent toxicity of the chemical and how many people were exposed. After that, you review research published on comparable contaminations—cancer among victims at Chernobyl, say, or residents of Love Canal. The result, in theory, should yield a scientifically rigorous prediction of how likely the contamination was to make people sick.

When it comes to burn pits, however, that kind of risk assessment simply isn’t possible. In its report, HMD concedes that the Defense Department does not possess adequate data on Balad. It doesn’t know what was burned, or how often soldiers worked in the pits, or how many troops lived nearby, or how long they lived there. It doesn’t know the frequency of smoke exposure, or the combination of pollutants involved, or what other contamination soldiers might have been exposed to, either on base or off. The Pentagon was conducting a war, not a science experiment. And as in past wars, it did not pause to assess whether its own practices—something as seemingly mundane as burning trash—might be placing soldiers at serious risk. After Vietnam, the government was unable to say exactly how much Agent Orange soldiers were exposed to. After the Gulf War, it could not account for the combination of toxic elements that contributed to veterans falling ill: depleted uranium, smoke from burning oil wells, vaccinations, sarin gas. The VA, in fact, still refuses to refer to the debilitating condition suffered by Gulf War vets as a “syndrome.” It prefers a more revealing term: “medically unexplained illnesses.” For the military, the health and well-being of veterans is simply another known unknown.

Faced with a lack of accurate data on human exposure in Iraq and Afghanistan, HMD had a clear alternative, one that would meet the prevailing scientific standard for such research: a review of toxicity studies on animals. While such a review would not be comprehensive, it would help determine whether burn pits had made soldiers sick. That, in turn, would allow veterans to know if their ailments were service-related, which would force the VA to provide them with treatment and disability. But instead of following established scientific protocol, HMD made a decision that fatally undercut its findings: It refused to consider animal studies in reaching its conclusions.

HMD researchers had been working for years to skew their studies in favor of the VA. In 1994, when HMD published its first study on the impact of Agent Orange on U.S. soldiers, its own research standards required it to rely on both human and animal studies. That study confirmed a link between Agent Orange, a military herbicide, and widespread health problems among Vietnam vets.

By 1998, though, when HMD began its studies of Gulf War exposures, it had made a subtle but significant change to its standards for “categories of evidence.” Animal studies could still be discussed in its reports, but they were no longer considered valid evidence as part of its final conclusions. The science, in short, was being rigged to reach a desired outcome.

A year earlier, a congressional investigation had called the government’s approach to studying Gulf War illnesses “irreparably flawed.” In response, Congress created the Research Advisory Committee to conduct an independent study. The RAC reviewed evidence from nearly 2,000 scientific studies and government reports, including both human and animal studies. Unlike HMD, which stated that it was not its responsibility “to determine whether a unique Gulf War syndrome exists,” the RAC found that the illness was “real” and that it “affects at least one-fourth of those who served in the war, is not associated with psychiatric illness, and was caused by toxic exposures including pesticides, pyridostigmine bromide pills, and possibly oil well fires, multiple vaccinations, and low-level nerve gas released by the destruction of Iraqi facilities.”

When it came time to study burn pits, however, HMD once again relied on flawed methodology. Lacking human data on Balad, researchers decided instead to look at two nonmilitary populations it defined as similar to soldiers who served at Balad: firefighters, including those exposed to chemical blazes and wildfires, as well as incinerator workers. HMD acknowledged that the experience of firefighters is “likely to differ from the chronic exposures to burn-pit emissions that military personnel experience.” But it still contended that this group was “the best available representation of exposures to mixtures of combustion products.”

It’s not hard to see how HMD’s methodology would corrupt its findings. Firefighters inhale smoke only for brief periods, unlike the around-the-clock exposure experienced by soldiers who lived and worked next to burn pits in Iraq and Afghanistan. And incinerator workers, by definition, inhale cleaner-burning smoke that has been run through an incinerator—the very same equipment that KBR failed to deploy at Balad and other military bases. Demonstrating a low risk to firefighters and incinerator workers would tell you next to nothing about the connection between burn pits and ailing veterans.

“You have a concern about people coming back, people getting ill, and then do you go do a study by comparing their health to people back home?” says James Binns, who chaired the RAC that studied Gulf War illnesses. “This was a study designed not to detect the problems, but to dilute the problems.”

In an email to the New Republic, HMD defended its methodology. It cited the complex mix of chemicals released by the burn pits, and said that it did not know “if the black smoke that everyone complained about had been sampled.” While it would have been “nice,” HMD added, to have reliable studies in which animals were exposed to burn-pit emissions with the same intensity and frequency as soldiers, “these types of studies are difficult, expensive, and time-consuming to conduct.”

The VA employed a similar form of scientific self-dealing in 2009, when it conducted a national survey on the health of more than 20,500 veterans who had been deployed during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Steven Coughlin, a senior epidemiologist at the VA’s Office of Public Health, used data from the survey to study the link between burn-pit exposure and respiratory illnesses such as asthma and bronchitis. Coughlin, who had run the public health ethics program at Tulane University and who co-wrote the ethics guidelines for the American College of Epidemiology, found a positive correlation between soldiers exposed to the burn pits in Iraq and Afghanistan and the onset of chronic ailments. But when he shared his findings with his supervisor at the VA, he was ordered to stop looking into the data for such connections.

“We set the findings aside,” Coughlin says. “Tabled them. Discarded them. They decided not to include the burn-pit exposures, and focus simply on the frequency of respiratory illness. They wanted to ‘simplify’ the analysis. It became clear that they were trying to suppress the findings and downplay the associations instead of highlighting them.”

Coughlin resigned from the VA in 2012. It was untenable, he concluded, to conduct scientific research on behalf of an agency that, like any insurance company, had a direct financial motivation to deny claims to its patients. “There’s a conflict of interest within the VA,” Coughlin says. “As they find new deployment-related health conditions, like the conditions associated with Agent Orange exposure during Vietnam, it ends up costing them billions of dollars.”

In a sense, the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq began with a burn pit. When the Twin Towers collapsed on September 11, the bombing incinerated hundreds of thousands of tons of cement, steel, drywall, window glass, computers, and electrical cables. A toxic plume arose from the site, and the dust that settled over the city included the remains of the 2,753 people killed in the attack. It was, in more ways than one, a foreshadowing of what was to come.

In the weeks following the attacks, the Environmental Protection Agency assured New Yorkers that the dust and smoke from Ground Zero did not pose a health risk. But by the time the United States invaded Iraq in 2003, it had become clear that those assurances were a lie driven not by science, but by politics: The Bush administration, it turned out, had pressured the EPA to downplay the risk posed by Ground Zero exposure. As 9/11 first responders began to develop cancer and die, the government fell into the pattern of evasion that continues to this day: deny the problem exists, delay taking action for as long as possible, create a registry of those who complain, order a study, spin the findings, and then order another study.

In June 2015, the VA finally published findings drawn from the burn-pit registry, based on questionnaires completed by 27,000 veterans who said they had been exposed to burn pits. (Nearly all of the vets also reported being exposed to dust storms at some point during their deployment.) Those exposed to burn pits suffered from higher rates of asthma, emphysema, and rare lung disorders. Thirty percent had been diagnosed with respiratory diseases, including serious disorders like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and chronic bronchitis. Three hundred and sixty five veterans said they had been diagnosed with constrictive bronchiolitis or idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, another incurable lung disease, typically not found in young, fit populations.

Such numbers almost certainly underestimate the scope and severity of the health crisis among veterans of America’s wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Many cancers don’t reveal themselves for a decade or more, and many serious respiratory symptoms tend to be misdiagnosed as asthma. When veterans develop respiratory disorders after they return home, doctors may fail to make a connection between their symptoms and their military service. The truth is, we may never have a full scientific understanding of the pain and suffering that the burn pits inflicted on U.S. soldiers. And the VA is taking advantage of that fact to withhold medical treatment and disability benefits from those who were injured overseas. For veterans exposed to the burn pits, the equation is simple: Every delay by the government means less treatment, higher medical costs, and a greater risk of death.

In February 2015, Jessey and Maria Baca traveled to New York City. They had put together a “bucket list” of things Jessey wanted to do before he died, and visiting the city was on it. When I meet them in the lobby of a Holiday Inn on Wall Street, not far from the World Trade Center site, Jessey shows me a red welt on his cheek.

“No idea why,” he says. “Weird new things all the time.”

“This is him on a good day,” Maria adds.

“It feels like a cactus growing in my lungs,” Jessey says. “I can breathe in, but not always out.”

Maria tells me that another of the veterans who worked to create the burn-pit registry had died. Bill McKenna didn’t live to see the registry open: He died of a cancerous mass on his heart in 2010. He was 42 years old and had never smoked.

Baca knows he has been treated unfairly. But he is glad that he managed to receive a diagnosis before he dies, and that he forced the government to acknowledge he was injured in service to his country. “I’m one of the lucky ones,” he says.

I ask why he thinks that.

“The worst part was the unknown,” he says. “I didn’t want to die of the unknown.”