Rio’s manic preparations for this year’s Summer Olympics have now become a familiar subplot to the sports themselves. More than 77,000 people have been displaced from their homes between 2009 and 2015 in Olympics-related redevelopment. Many found themselves not just out of a home, but pushed to remote peripheries of the city without access to social networks, public transportation, or employment opportunities. Entire communities, like the fishing village of Vila Autodromo, have been cleared, a faithful execution of the renderings presented in Brazil’s original bid to the International Olympic Committee, in which the settlement was conveniently airbrushed out. In favelas that are not cleared but subject to intense patrols, hundreds of residents have fallen victim to Brazil’s military police—or what Amnesty International called a “trigger-happy” force that seems to be conducting a “shoot first, ask questions later” strategy in its pacification campaign.

Some reporters have left the Olympic venues long enough to show us glimpses of the still-simmering unrest, from the Olympic torch relay, during which protesters lobbed stones and the riot cops retaliated with tear gas and rubber bullets, to the viral photos of children watching the Opening Ceremony’s glittering spectacle from their distant perch in the mountainside favelas. The popular anger against Olympic excess, which comes on top of the outrage displayed just two years ago during the World Cup, is compounded by a rolling national political crisis in which the presidency and the country’s future hang in the balance.

The IOC has stated that one of its criteria for site selection is to give the opportunity to countries that have never hosted before. In turn, nations selected as first-time Olympic hosts become consumed in the grand project of demonstrating their modernity and progress to visitors, whatever the cost. For many recent hosts, like Beijing, Sochi, and now, Rio, that cost has stirred serious domestic controversy.

However familiar the story of Olympics-related displacement may be, what often goes unremarked is the displacement yet to come. For many, the Olympics serve as a pretext for accelerated real estate speculation in areas settled by the poorest and most vulnerable. The speed and scale of the required construction often sets in motion a number of mechanisms that enable wholesale gentrification: massive land purchases, the state’s use of eminent domain to seize the private land of mostly poor residents, the relinquishment of public land to private entities, and the creation of non-elected private bodies to manage the process. The special procedures, bypassed laws, and closed-door decision-making all give the overwhelming impression that the Olympics is where the democratic process goes to die.

In Rio, for example, 75 percent of the Olympic Park will be turned over to private developers after the Games are done. The committee in charge of redevelopment was led by real estate scions, and unsurprisingly, the most apparent beneficiaries of the Games so far are the same industry players.

All these elements—and worse—were evident in the Seoul Olympic Games in 1988, which helped set the template for the modern “Olympification” of cities in the developing world. As we start to look toward the next Olympics—the 2018 Winter Games in Pyeongchang, South Korea—it’s worth looking back at the 1988 Summer Games to see what’s in store for other cities tempted to use the Olympics as a fast track to development.

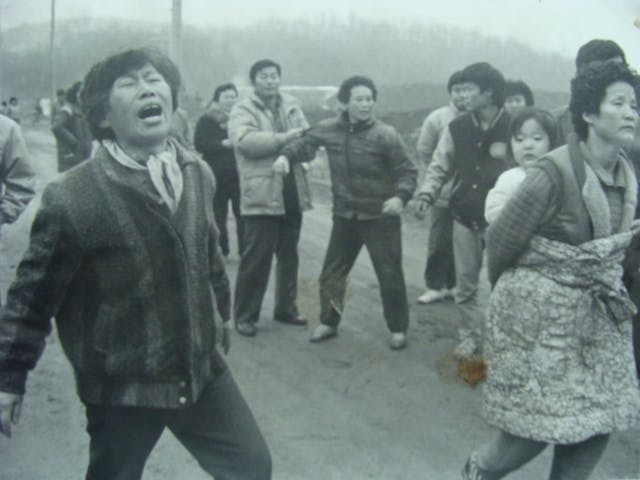

In the lead-up to the 1988 Games, the residents of Sanggyedong, a poor Seoul neighborhood, fought against the riot police and the thugs hired to kick them off the land for Olympic redevelopment. A documentary about their protracted struggle, Sanggye-dong Olympics, was shot by a young filmmaker who had intended to document a single day but instead spent three years living in the neighborhood, fully absorbed within its daily routines and skirmishes. The footage is unforgettable and harrowing—women lying prone beneath the construction cranes to stop them, and grandmothers staying up all night with bats to guard against night evictions.

Inevitably the confrontations turned violent, as hired muscle beat anyone who resisted with steel pipes and sledgehammered through houses still filled with residents’ possessions, while the police hauled off screaming residents. But even after being evicted, the residents refused to leave the land, living in makeshift shelters, cooking together outdoors, and covering their children with layers of blankets through the freezing winter. “Protect the human rights of poor people” was one of the slogans strung on banners around the area.

Eventually the residents were resettled to another area on the outskirts of Seoul, but faced eviction for the second time when it turned out their shantytown was located along the Olympic torch route. The film ended with an epigraph: “Olympic guests will rest assured they will not suffer the discomfort of seeing a single poor person in Seoul.”

Only recently did I learn that some of my relatives had lived in Sanggyedong in those days. My aunt on my father’s side offered this fact as an off-hand comment, but she never talked about the evictions. I could hardly imagine her criticizing the government. She had lived through several military dictatorships, and didn’t trust that criticism wasn’t punishable with jail or worse.

The 1988 Olympics did not just spur a construction boom of stadiums and apartment towers. They also catalyzed a larger turning point in Korea’s national culture and politics. Korea in 1988 was a fledgling democracy, emerging only the year before from four decades of U.S.-backed military dictatorships. Nearly a decade earlier, in 1979, dictator Park Chung-hee (the father of the current South Korean president, Park Geun-hye) had decided to bid for the Olympics. But he was assassinated only a few months later. After a brief period of hope for civilian rule, military general Chun Doo-hwan staged a coup in 1979 to gain the presidential seat. He decided to proceed with the Olympic bid, which was approved in 1981 despite his subsequent declaration of martial rule, a bloody crackdown on pro-democracy protesters, and his dissolution of the national parliament in 1980. For Chun, bidding for the Olympics was part of a larger strategy to distract citizens from the political and economic struggles taking place, otherwise called the 3S policy of promoting “sports, sex, and screen.”

Chun’s rule mirrored Park’s, even as he vowed to build a different kind of regime. He continued the torture and imprisonment of dissidents and blocked all avenues to independent and fair elections. This led to unprecedented mass protests in 1987, in which tens of thousands of people marched in the streets. These protests, along with the specter of the whole world observing South Korea on the eve of its Olympic debut, led to Chun’s hand-picked successor agreeing in 1987 to the first free elections in the country’s modern history.

Thus 1988 represented an opening in more ways than one. In a country that still had strict limitations on international travel, where sports and leisure activities were relatively new cultural phenomena, and books and movies still heavily censored, the Olympics signified a break from an authoritarian past, instead of lending legitimacy to it.

But before Chun stepped down, he had already used strong-arm tactics to ready the country for its global debut. In the five years leading up to the Games, an estimated 48,000 buildings were destroyed, displacing 720,000 people. The U.N. fact-finding delegation that came to document what happened said the Olympics had set Korea’s “neurotic development” on warp speed. Visitors streamed in from around the globe, astonished that Korea looked so, well, modern. But the gleaming capital unveiled for the Summer Games was, in fact, the product of two back-to-back military dictatorships and their unchecked power to transform the urban landscape.

More recently, it has come to light that during the years leading up to the Olympics, beginning under Park’s presidency, policemen and local officials had waged a “purification” campaign, sweeping the streets of more than 16,000 unattended children, disabled people, panhandlers, homeless people, and dissidents, and locked them up in dozens of institutions without giving notice to their families. Thousands were raped, beaten, and killed during their imprisonment, while those who survived the violence toiled in factories or on construction sites all day for no pay. At the most notorious of these institutions, Brothers Home, four to five inmates died every day from violence committed by the guards.

All of this happened with the full knowledge and approval of the country’s leadership, while the owners of these institutions were rewarded with medals for social welfare. To this day, they have not been punished. Even when the owners were pursued on legal charges in 1988, presidential officials continually blocked the investigation on the grounds that the resulting scandal would only embarrass the country on the eve of its Olympic debut. When asked by the AP about the deaths, a former official from Brothers only offered, “These were people who would have died in the streets anyway.”

This past New Year’s Eve, I was in Gangneung, a city on the east coast of South Korea, to celebrate the holiday with my relatives. I asked my uncle, as I always do, to take me to my mother’s childhood home, located on a rural road where I would not trust GPS to guide me. This was where my mother spent her childhood after surviving the Korean War, living with her grandparents in a traditional house with a thatched roof and papered sliding doors, a house where the family had lived for generations. Nowadays, only one of my relatives still makes a living as a farmer in the area. Whenever I visit, his elderly neighbors, wizened and bent over from their farm work, peer into my face and exclaim my mother’s name.

As we drove to the house, I noticed a series of monumental concrete arches dotting the landscape. They were the tallest structures around, five to six stories high, in an otherwise flat vista of rice fields and one-story homes. Curiously, they didn’t follow the road. Instead they seemed to exhibit their own logic, often landing squarely within meadows and fields.

My uncle parked the car on a narrow road and announced, “Here we are!” I was shocked to see the arches continue straight through the field that held my mother’s old house. Several loomed just ten yards from us.

“But what’s all that?” I asked, pointing upward.

My uncle peered up. “That’s for the high-speed rail. They’re building it for the Pyeongchang Olympics.”

“They’re also building ice rinks along the coast,” my aunt added. “The Olympics are coming here too! We’re thinking of volunteering. But we’ll see.”

There was a quiet pride in her voice. I could understand it—there was obviously some prestige in Korea being selected to host the 2018 Winter Olympics. For her, there was the added pride that Gangwon province, an agricultural region known mostly for its potatoes and beaches and its proximity to North Korea, would be hosting the most iconic sporting event in the world. There was a general excitement in the air about the prospect of hosting the Games—another chance to prove South Korea’s status as a global contender.

Looking up at the arches, I envisioned the train whooshing past, filled with dignitaries and tourists oblivious to the ancient, crumbling house below. The high-speed rail was one of the cornerstones of South Korea’s winning bid to the IOC. Korea had promised that visitors would be able to travel directly from the international airport to Pyeongchang in 68 minutes—a projection that was later pushed back to 93 minutes. The city of Gangneung, only thirty minutes from Pyeongchang, will boast a total of four ice stadiums and host all the indoor sporting events.

Pyeongchang’s winning bid was the legacy of former President Lee Myung Bak, who built his career as the CEO of Hyundai Construction and spent much of his presidency bestowing generous federal contracts on the construction industry, earning him the nickname “Bulldozer.” In his presentation to the IOC, Lee pointed out that 19 of the last 21 Winter Games had been held in Europe or North America. Didn’t Asia deserve a chance?

Standing in the shadow of the giant arches, I felt a sharp sense of loss. I had always assumed that breakneck urban development was a central feature of life in Seoul, the nation’s capital. But in this part of the country, known mostly for its natural vistas, where the elderly tended to stay and the young people disembarked for new lives in Seoul, a high-speed rail seemed excessively optimistic and all too permanent. I tried to imagine a future where, after the world’s top athletes had packed their bags, Seoulites would visit Pyeongchang in droves to luge and curl and bobsled. This had been the IOC’s main draw for selecting Korea—it represented a new market for winter sports. But beyond cheering for Olympic figure skater Kim Yuna, Koreans are not winter sports enthusiasts. It seemed more likely that, after the Games ended, the high-speed rail would become a long, snaking ruin, looming silently over the countryside like a hollow promise.

When the 2018 Winter Olympics kick off in Pyeongchang, 30 years will have passed since the 1988 Seoul Olympics. Traveling back to Seoul after the New Year’s holiday, I noticed that at City Hall and the National Assembly, at the plazas, the subway stations, and even on billboards, tent occupations and rallies and other signs of dissent were on display, flourishing everywhere even in the freezing temperatures. It was a hopeful sign that the political climate in Korea had changed since the ‘80s—and yet it was disheartening, too, a reminder that some things haven’t changed. As the Olympics leave Rio, and as we look ahead to Pyeongchang and beyond, the question remains troublingly unresolved: Does Olympification always have to mean mass displacement? What does it mean to host the world if you cannot house your own citizens?