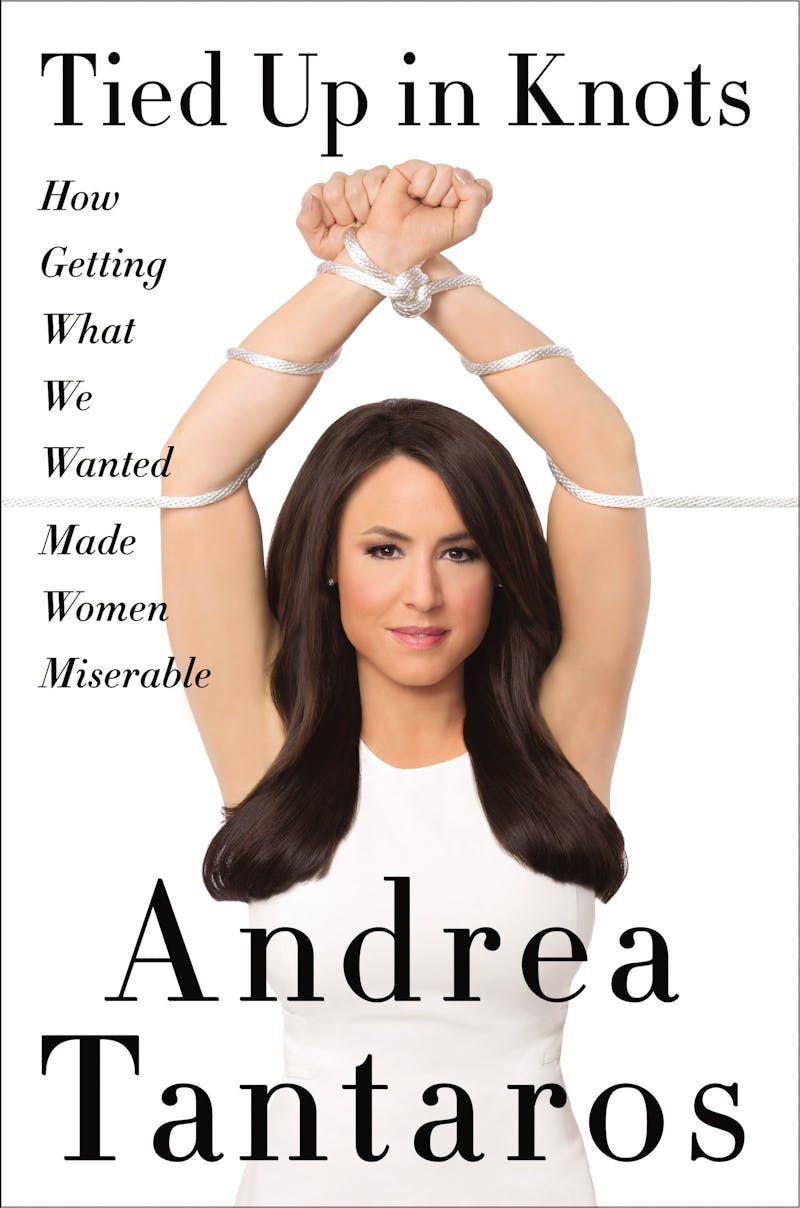

Andrea Tantaros is worried about you. Best known to an American audience for her appearances on Fox News, Tantaros is adding “author” to her résumé with the release of a book, Tied Up in Knots: How Getting What We Wanted Made Women Miserable. According to Andrea Tantaros, feminism’s quest is over: We have shattered the glass ceiling, grabbed the brass ring, and accomplished whatever other metaphorical task you want to throw into the mix. Or, as Tantaros puts it, “We won.” This view suggests, in essence, that feminism had a finite goal, and that we have reached it.

Yet, she cautions, this victory has come at a steep price. If you are a woman who came of age after women’s liberation, Tantaros claims, your understanding of love and intimacy has likely been stunted by a dangerous cabal she refers to as “the feminists.” According to Tantaros, we are in the midst of relationship crisis, and America’s youth are poorly equipped at fostering trusting and meaningful relationships with romantic partners.

The victory of “the feminists” has destroyed not just relationships, but workplaces. “Many people,” Tantaros writes, “especially early feminists, hoped that camaraderie among women would flourish in an environment that celebrated and facilitated female advancement. They hoped that more power in the workplace would lead to more mentoring, more unity, and the fostering of female growth and bonding. But more women working has made room for more malice.” By trying to emulate men, women have undermined each other’s progress.

And to an extent, Tantaros is right. One of the greatest missteps of second-wave feminism was its willingness to equate power with progress. But the most fascinating and maddening thing about Tied Up in Knots is Tantaros’s ability to point out real problems, only to arrive at simplistic explanations for them. A meaningful shift in contemporary feminism has been our growing understanding that co-opting existing power structures often merely serves to replicate old forms of oppression.

For every one of Tantaros’s claims that I disagreed with, however, I remain far more affected by the aspects of her arguments that rang true to me. I read Tied Up in Knots because I wanted to see if I—as a radical feminist, lover of queer theory, and card-carrying member of generation woke—could learn from a conservative woman’s perspectives on feminism. The fact that I was able to makes me believe that we can, and must, communicate about feminism across party lines. Andrea Tantaros and I probably disagree about almost everything, but this much is clear to us despite our opposite leanings: A revolution is bound to fail us if its sole end game is winning the enemy’s power.

There are many glaring problems to take into account when we try to discuss feminist issues across the political divide. To Tantaros, the word “feminism” alone means something very different than it does to many women her age who actually identify as such. Tied Up in Knots comments not so much on feminism as it was forty years ago, but on the most simplified version of that movement. There is not a whisper of the profoundly influential—and at times dramatically divergent—opinions espoused by such feminist thinkers as Shulamith Firestone, Audre Lorde, Andrea Dworkin, bell hooks, and Roxane Gay. Absent from the book, too, is an exploration of class, race, trans rights, or intersectionality of any kind. For Tantaros, “feminism” essentially means workplace progress and sexual aggression.

Her view of the pre-feminist past is similarly simplistic. She falls back on the assumption that there was some halcyon time when things simply worked—when men were men and women were women, and marriages and relationships made sense. It’s a compelling fantasy, and one that offers far more comfort than the alternative argument: that there has never been an era during which the majority of heterosexual couples have forged loving and egalitarian relationships, and that we now must work not to return to traditional values, but to pioneer a new way of life.

In one of Tantaros’s backstage Fox New anecdotes—of which this book contains far too few—she finds herself debating a return to “traditional values” with Bill O’Reilly. O’Reilly believes such a shift is possible, but only “If a leader emerges, in the mold of JFK.” Tantaros disagrees. “We’ve gone too far,” she tells him. “There’s no putting the genie back in the bottle… It’s a Tinder nation.”

“What’s Tinder?” Bill O’Reilly asks.

Tragically, Tantaros doesn’t describe the ensuing explanation, but she does tell us exactly what she thinks of Tinder: namely, that it’s destroying dating, monogamy, and intimacy between women and men.

“People are routinely having sex with each other after fewer than ten messages,” Tantaros laments. “This is unprecedented.”

It’s not, of course: People have been having sex following minimal communication for as long as we’ve known how to have sex at all. Yet a curiously large section of Tied Up in Knots is dedicated to The Trouble with Tinder, which suggests that Tantaros’s wholesale dismissal of it might mask a more complicated reaction on her part. Casual sex is an arena of potential intimacy, and Tied Up in Knots is, more than anything, compelled by the question of where intimacy has fled to in this modern world. Tantaros denies that any form of true connection is possible within a “Tinder nation,” but more troubling might be the dating app’s potential. For Tantaros and other conservatives like her, is there a worrying possibility that Tinder is not a destroyer of intimacy after all, but a realm of fluid sexualities and female assertiveness where intimacy can flourish?

The grimmest moments in Tied Up in Knots, however, are not those when Tantaros bemoans a disintegrating society, but when she presents her ideal of gender relations. “When my mother went to Bible study,” Tantaros reminisces,

the pastor’s wife told all the women there the following: ‘When he comes home… Brush your hair and put on some lipstick. It takes literally less than a minute. And whenever he wants sex, you give it to him. You always give him attention when he wants it. If you don’t, there will be another woman who will.’

“The deal has never changed,” Tantaros argues. “Men have sexual needs, and women have emotional needs. The guy is happy getting sex, and the girl is happy when he listens to her story about her stupid coworker who stole her idea and didn’t give her credit for it. We’re not biologically the same. But this should be a source of strength.” There is no room for true intimacy in this landscape. Instead, acts of love become contractual obligations. Women must earn the right to be listened to, and men must earn the right to have sex.

According to Andrea Tantaros, apps like Tinder have furthered the work feminism has already done to destroy romantic relationships, because if men don’t have to work for sex, there’s no reason for them to act civilized at all. Further, if women appropriate masculine behavior and act promiscuous and aggressive, then men will feel neglected and unloved. “I think both genders are deeply unhappy,” Tantaros writes. “They’re deeply distrustful of the other sex.” And the situation, she argues, is growing steadily worse: “The apps are only getting more sophisticated.”

The most compelling thing about Tied Up in Knots is that the book makes such a persuasive case for an argument that doesn’t seem to have occurred to Andrea Tantaros herself. “Women can choose,” she writes in her final rallying cry. “We can choose how to apply our power. We can insist on respect. We can demand monogamy… We can choose kindness. We can choose authenticity. We can choose to refuse. We can choose discretion. We can pursue and preserve intimacy in our relationships.” The truth is that, as a society, we do need to be rescued from the destructive power of patriarchal masculinity. We need to question any doctrine that equates feminism with co-opting patriarchal power structures. And we need to “choose kindness,” exactly as Andrea Tantaros says.

Tantaros also believes that biologically dictated masculine behavior can only be balanced by an equally extreme performance of feminine behavior, leading to a society in which we must, apparently, constantly work to maintain equilibrium between two extremes. The possibility she does not consider—but one her book’s conclusion inevitably gestures toward—is that the obligatory performance of gender roles harms us all. Tantaros is right in her claims that women should not mimic patriarchal masculinity in their search for empowerment. What she fails to recognize is that no one, regardless of their gender identity, should feel “tied up” by patriarchal norms of aggression and emotionlessness.

Reading Tied Up in Knots means recognizing that the compulsory assumption of gender roles forces us to suffer in ways no one can ignore—even as they attempt to argue that this role-playing will save us. In trying to show us all the damage feminism has done, Tantaros instead demonstrates the damage it has yet to repair. We haven’t won, and we never will win, because there is no such thing as winning. Instead, all we can do is work toward a society that regards romantic relationships not as marketplaces, but as spaces for mutual warmth and vulnerability. In 2016, “Choose kindness” can mean nothing else.